The daughter of a Vietnam Veteran, a US Navy Veteran herself, recently wrote a college thesis about communications during our war and how it affected the families of those deployed. It’s a great read that caused me to reflect on my own tour of duty and how it may have affected those back home.

I was first contacted by Djinni in the early fall when she requested permission to share some of the stories from my website and to quote me a couple of times in a term paper she was writing for her Bachelor Degree in Communications from the University of Utah. Her topic was about communications from Nam between US soldiers and their loved ones. Her father served in Vietnam and some of what she’s written is from her personal experience. Djinni is a US Navy veteran, married, and has three incredible kids.

University of Utah

An analysis of distant family relations and its effect

My father was deployed to Vietnam as a civilian safety officer working for Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) during the Vietnam War. I remember getting letters occasionally from my Dad; and they were usually written very simply with a lot of pictograms and text, often saying something like, “How are you? I am fine,” and ending with “I love you” written with drawings of an eye, a heart, and a letter “U,” My mother would get personal letters and cassette tapes. My mother shared many of the cassette tapes with our family, so we could hear our father’s voice and know what my Dad was doing. I only know what I remember my Dad sharing with us, and it was possibly sugar-coated. Inspired by my experience at home and communicating with my Dad during the Vietnam War. I have a desire to know how the experience my family had compares with other family’s experiences. This research was conducted by interviewing Vietnam veterans, family, some of which were corresponded through email and messaging, and researching military websites. Throughout this document, I will refer to all genders of enlisted US Armed Forces as GI’s and service members since that is what they were called during the Vietnam era, except sailors in the Navy. The quality of communication increases the odds of success in family relationships.

In 1972 my Dad left Utah and was deployed to Vietnam as a civilian. My mother was about 39 and had six children living at home, one married and one on an LDS mission in Austria. The youngest child at home was only between three and four. My mom had to manage the entire household with some help from her teenage kids. The most challenging thing I imagine for her was missing her husband and the chance that he would not return. My oldest sister Christine was about 21, and she was living in Kamloops, British Columbia. Christine said Canadians hated Americans in the early ‘70s since so many Americans were moving to Canada to escape being drafted into the military and sent to Vietnam. Christine says she was confronted in church for trying to avoid the war and defended herself by saying that her Dad was serving in Vietnam. She identifies as a Pro-Hawk, believing we needed to be there, but understood that there was no way to win this kind of war. Christine was proud of her Dad for going to Vietnam. She also says the war was unpopular, so guys her age would lie about being in the service when they came back so that they could get hired.

The Military Auxiliary Radio System (MARS) is a US Department of Defense sponsored program run by civilians and active-duty military personnel. MARS provides two-way radio emergency communication worldwide, which can reach outside the bands of HAM radio. Thousands of amateur radio operators provide much of this service. During the Vietnam War, servicemen were allowed to contact their families through “phone patches” live phone calls and “Marsgram” written messages. MARS radio is still in operation currently. One of its missions is to boost the morale of servicemen and women as well as other US government employees, although less frequent now than in previous decades. MARS also supports other government agencies such as The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). Mars is available on both land and sea. However, the Navy-Marine Corps MARS shut down in September 2015. (Pg. 3 MARS a Brief History.pdf)

MARS radio stations on military installations have been operated by both government professionals as well as civilian amateurs, some of which have been volunteers. HAM radio requires a bit of knowledge and skill to function. Different levels of licensing provide operators with different rights, such as how far an operator can transmit. Some of the equipment required to start is a transceiver, power supply, antenna, tuner, microphone, and cables. Operators not only have to learn how to operate equipment, they also have to learn communication codes that are made up of letters and numbers. Some of the relevant social groups include the operator, the receiver, the FCC, Repeaters, The American Radio Relay League (ARRL), various repairmen, and manufacturers. For the radio transmission to be successful, it requires heterogeneous engineers. The combination of skills, people, artifacts, and nature creates balance in a successful system. If just one-part malfunctions, the communication technology can be disastrous. For example, if someone used the wrong code in an emergency, the wrong kind of assistance could be sent, and with possibly less urgency, or a navigational mistake could send someone off course. Other failures in the network could be with the equipment such as the power supply or any other part. The most challenging thing to control in this network is the natural phenomena, such as a technician having a panic attack when hearing details of an emergency, or a hurricane interfering with the quality of transmission (Law).

Eric Richhart joined the Navy in 1969 when he was 17 years old as a Radioman. He was single and stationed on the USS Mauna Kea. The Mauna Kea was an ammunition ship that supplied other warships. The ship would go out to sea for about nine months at a time and sometimes stop in Hawaii or the Philippines. Richhart worked with the MARS radio. He says mail would take a long time to get to family in the United States because it would have to stop several military bases on the way such as Hawaii and the Philippines before it reached the ship from the Fleet Post Office (FPO). Sometimes mail would come from an aircraft carrier. Richhart says the American Red Cross would contact sailors through the MARS station if there was an urgent message such as a fatality or a birth.

In the online veteran forum, DeltaOne said, his wife would send him photos of her and the kids. However, it made the separation more difficult, especially when she sent private photos of herself, it would “drive him nuts.” CWO Green said letters and cassettes from rather racy

girlfriends, were most highly prized and often shared with good buddies for entertainment. Although, if they were from wives, they never got shared.

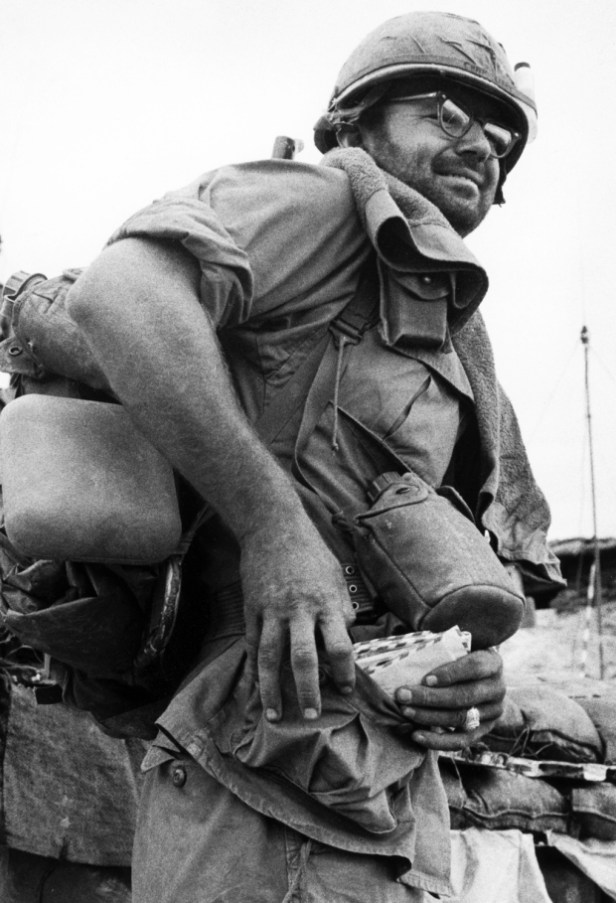

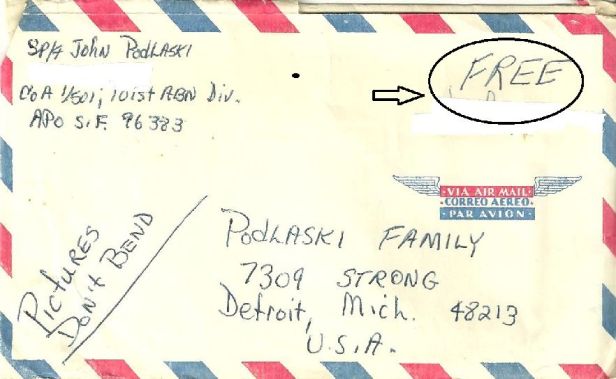

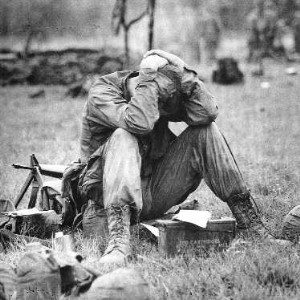

Many GI’s agree that receiving a breakup letter (AKA: A Dear John) was the most devastating kind of letter to receive. Green said Dear John’s were more frequent that one might imagine. Many relationships did not survive the year-long absence. People could always tell when a GI got a Dear John letter. His behavior would either include a lot of swearing and stomping, or he would go completely silent and deal with it privately in an unhealthy way. People knew when somebody was in the dumps over a Dear John. The feeling of betrayal, sadness, and absolute helplessness was often overpowering. Since there was no way for a GI to call home quickly or at all and no chance to confront the situation directly. John Podlaski says that just before he left for Vietnam, he gave the girlfriend. He had been dating an engagement ring. He said the frequency of the letters decreased, until finally, after three months of being in Vietnam, he received the letter he would remember for a lifetime. She told him she joined in the anti-war protests, she was in love with another guy, and she would take the ring to his mother. He said, “My childhood notions of romance suddenly shattered! I felt helpless because she was so far away. I couldn’t call. I couldn’t visit for a face-to-face. It was a major distraction, one that might get me killed. Overnight, I developed an “I don’t give a shit attitude,” volunteered to walk point, joined spontaneous ambush teams, and took all kinds of unnecessary risks.” Soon Podlaski’s buddies in ‘Nam recognized the signs that something was wrong, then he told them what happened. At that point, the support from his brothers in arms and the support from his community saved him from utter self-destruction.

Some of the favorite items in a “Care Package” were foods like presweetened Kool-Aid that could disguise the taste of the water in their canteens and condiments like hot sauce to cover the bad taste of the MRE’s. Green said he received many wonderful packages from girlfriends along with letters, Most had treats of some kind in them, including cookies, cakes, candy, packaged soups, coffee, and tea. “Anything the mess hall or the PX could not serve up to eat or drink was precious.” They often traded many items with other GI’s. Podlaski said, “if somebody in your squad got a care package from home, it was like winning “The Publisher’s Clearing House Sweepstakes.”

One likely reason many of us did not feel the impact of a dangerous war situation at the time, was due to the exchange of quality communication. The success of our family network was due to communication skills of each family member, the people within the postal service, MARS service, HAM radio, the phone company, the paper company, the pen and ink companies, and many more silent partners balanced with nature. As I reflect on my research to find out how the experience my family had compared with experiences from other families, I see a correlation with the quality of communication and the success of a family. Many other families may have also had excellent communication. However, the nature of war changed the course of their success through unfortunate events. My family was blessed to have my Dad return home healthy and mentally stable. The inventors of the cassette player, HAM radio, and other communication artifacts did not likely realize the role it would have in the Vietnam War and social effects the technology would have on the actors involved.

Bibliography

Primary Sources (Face-to-face, Facebook Messenger and phone)

Gibson, Larry U.S. Navy Petty Officer (Face-to-Face)

Online Sources (Web)

Photos:

GI puts mail in his pocket https://www.stripes.com/blogs-archive/archive-photo-of-the-day/archive-photo-of-the-day1.9717/mail-call-in-vietnam-1968-1.272103#.XeG_hJNKi-s

MARS Radio https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Commons:Reusing_content_outside_Wikimedia http://www.defenseimagery.mil

John Podlaski’s Envelope https://cherrieswriter.com/2013/11/01/mail-call-in-vietnam-dear-john/

Had to laugh when I read the Mars call information. I had a friend who needed to call his wife to inform her of his R&R time so they could meet in Hawaii. after giving him a ride to the communication building I thought while I was waiting for him that I would call home too. Just for informational purposes my father hated to talk on the phone and seldom if ever answers it. I can hear the MARS call operator explaining the procedure to him at which time I say hello dad over his response where are you at over I say Viet Nam over his response what do you want over my response nothing I guess over his response nobody else here googd bye over. When I returned home and for years after we got a good laugh every time that story was told.

LikeLike

I was impressed with the author’s research and this did awaken some memories. However, in the vein of constructive comments I would point out a couple of small mistakes in the “Care Package” section. During the Vietnam War MRE’s didn’t exist, field rations consisted of C Rations and LRRPs, which points up the second glitch; LRRPs (Long Range Reconnaissance Patrol meals) WERE freeze-dried meals, so they did exist and in fact made up one-third of the normal fare for troops in the field.

But neither of these little things detracts from the value of this paper. I congratulate the author on a valuable piece of research that enriches the written history of the Vietnam War period.

LikeLike

About C-Rations. I ate, whatever I got. However, I liked, HAM & EGGS chopped.

When possible, I’d trade with whomever. And get, them.

LikeLike

Here’s some facts, about the MESS. In the Nam. We had no legit reason for, going there.

All those Americans who were, killed and died there. Died, for nothing. We had no blankety blank business there. I spent 1 yr. there. Early May of 70 to early May 71.

Half my time based in LB Post. Last half in, Quang Tri.

LikeLike

it a long paper, i will read it later thankyou for forwarding to share i will absorb every word she wrote for sure i have come down with the flu or some kind of flu freezing to death upset stomach you name it so going back to bed DID YOU SEE WHAT I HAVE BEEN WRITTING ABOUT QUININE IN YOUR PILLS FOR MALARIA I POST THE SHOW BECAUSE IT ABOUT THE ARTHUR CANT REMEMBER HIS NAME THIS FLU HAS EFFECTED OR THE FEVER HAS EFFECTED MY SIGHT SO I WILL READ IT WHEN I FEEL BETTER THANK YOU FOR SHARING I WILL COME BACK TO THIS !!

DO NOT GET THIS FLU GOING AROUND ITS HORRIBLE I HAD MY DAUGHTER HOME FOR ALMOST 2 WEEKS AND NO EATING ME MY SIGHT BEING FFECTED THINKING FEVER MAKE IT WORSE TALK LATER

M Dutil-Morin http://www.we-r-unique.ca (not .com!) French Genealogy

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article is almost like , all the others. OK

LikeLike

Dear Djinni,

Thanks for sharing your project. Keep it going. Maybe you can grow it into a doctoral dissertation at the Vietnam War Center at Texas Tech. Those folks will soon be publishing a new, second edition, of my 1994 book — MARS: Calling Back to ‘The World’ From Vietnam — which is the definitive history of MARS operations, stations, users and operators during that era. The new second edition will be an e-book that people can purchase from Texas Tech. It will be out sometime during 2020. I am donating all the proceeds to the Center at Texas Tech. I originally research and wrote the book during 1990-19093 when I was National Public Relations Officer (AAA9PR) of Army Mars and the MARS columnist in WorldRadio Magazine. I also ran patches from the original MARS station at Fort Monmouth (I was a Professor of Business at Montclair State University at that time). During the war I operated from AB8AQ at the 8th RRFS at Phu Bai on my off-hours from my duties as an NCO at the 101st Airborne Division there.

The folks at Cherries have my contact info, although you can find me via Google. I am retired & live in Canandaigua, NY.

Best,

Paul Scipione

AA2AV

ex AB8AQ, Phu Bai, 69-70

ex K2USA, Fort Monmouth, 1990-93

scipione@geneseo.edu

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can you describe your, definition of incredible.

LikeLike

Reference the Mail situation while I was in SVN 69-70 our Australian postal service stopped delivering our mail from SVN my wife of only a month before I went to SVN did not get any mail from me for over six weeks, as you can imagine the distress this caused to her, I still got mail from her and all her distress came through her letters, this happened to all us Australian Military in SVN.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting perspective

LikeLiked by 1 person

I served in Vietnam 1971 both as a 11B and as a doorgunner with the 3/17 Air Cav. I didn’t get a “dear John” but was basically ignored by my girlfriend which is almost as bad. Three letters in 12 months. Guess who got ignored when I finally came home? I never used MARS. However, I do remember our MARS station taking a direct hit just as we cleared the flight line while flying out of Phu Loi

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done Djinni. Sure brought back some memories. I did two tours in Nam as a helicopter pilot. Both tours the MARS station was always down or had long lines of troops waiting in line. Communication back home my second tour was mostly by letters as you described. However, during my first tour my aircraft was equipped with a HF radio and at night I would take a load of GI’s up to about 10,000 feet and we would talk via. HAM relay with our families. My CO got word of what I was doing and I was ordered to report to his office. I thought, “Oh s***, I’m in trouble now.” Turns out he wanted to go on my next flight so he could talk with his wife. I strongly agree with one of your findings: Older GI’s with a strong religious belief had the most stable marriages. I can attest to that. Thanks again for a well researched and presented paper.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nicely done Djinni. Compared to today’s satellite communications abilities, we were pretty much in the dark ages in Vietnam. Sometimes, I think that was a good thing. Correspondence for all GI’s was the epitome of importance. I was married with one child when I left for Vietnam. I worried about the well being of my wife and child and heard from my wife usually weekly. I wrote as often as I could but remember having to really be creative since being a Dustoff pilot didn’t lend to much good news as a rule. Fortunately, I didn’t receive a Dear John letter which did strike several of our company members during my year in Vietnam. Almost nothing I can imagine was more devastating to the recipients. One, a fellow pilot, had to be hospitalized as he went off the deep end. My wife and I did exchange tapes once in awhile and as was mentioned, it was good to hear her voice as well as my almost two year old son’s voice. I, too, used the MARS station only once while at the USO in Saigon. It was ok but the ham radio protocol “over” after every statement confused my wife. Fortunately we met in Hawaii for my R&R with our son shortly after the MARS thing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was a great article. Student using her family experience of NAM to write a paper. I did the same when I graduated from Boise State. I was a NAM vet 3 times over. The correspondence is very important for morale factoring. I did not get DJ as some friends wrote me and let me know what was going on. This was in the early 60s. Solution; get wasted at the beer bar at Amarillo AFB. In NAM I was married with 2 kids. My wife and I tried to write as often as possible and exchanged cassette tapes. Tapes were a big plus to hear the voices and the background. Brought things closer. Used MARS only once. Could be confusing to someone not familiar. Over: Reply: Over where.

LikeLiked by 2 people