By Lt. Col (ret) Michael Christy

The defenders of these two special camps held their own against overwhelming odds. They suffered heavy casualties and lost many aircraft during the fight, and eventually, evacuated everyone. In the chaos, they left behind several American bodies, and it took two years before considering the area safe for a recovery team to enter. Read what happened during this battle in May 1968.

Kham Duc Special Forces Camp (A-105), was on the western fringes of Quang Tin Province, South Vietnam. In the spring of 1968, it was the only remaining border camp in Military Region I. Backup responsibility for the camp fell on the 23rd Infantry Division (Americal), based at Chu Lai on the far side of the province.

They had originally built the camp for President Diem, who enjoyed hunting in the area. The 1st Special Forces Detachment (A-727B) arrived in September 1963 and found the outpost to be an ideal border surveillance site with an existing airfield. The camp was on a narrow grassy plain surrounded by a rugged, virtually uninhabited jungle. Post dependents, camp followers, and merchants occupied the only village in the area, located across the airstrip. The Ngok Peng Bum ridge to the west and the Ngok Pe Xar mountain bordered the camp and airstrip, looming over Kham Duc to the east. Steeply banked streams full of rapids and waterfalls cut through the tropical wilderness. The Dak Mi River flowed past the camp over a mile distant, under the shadow of the Ngok Pe Xar. Five miles downriver was the small forward operating base of Ngok Tavak, defended by the 113-man 11th Mobile Strike Force Company with its eight Special Forces and three Australian advisors. Since Ngok Tavak was outside the friendly artillery range, 33 Marine artillerymen of Battery D, 2nd Battalion, 13th Marines, with two 105mm howitzers were at the outpost.

Ngok Tavak was attacked by an NVA Infantry Battalion

Capt. Christopher J. Silva, commander of Detachment A-105 helicoptered into Ngok Tavak on May 9, 1968, in response to growing signs of NVA presence in the area. Foul weather prevented his scheduled evening departure. A Kham Duc Civilian Irregular Defense (CIDG) platoon fleeing a local ambush also arrived and was posted to the outer perimeter. We later learned that the CIDG force contained VC infiltrators.

At 3:15 am on May 10, 1968, Ngok Tavak was attacked by an NVA infantry battalion. First, mortars and direct rocket fire followed by a frontal assault pounded the base. VC infiltrators dressed as Kham Duc CIDG soldiers moved toward the Marines in the fort yelling, “Don’t shoot, don’t shoot! Friendly, friendly” before lobbing grenades into the Marine howitzer positions and ran into the fort, where they shot several Marines with carbines and sliced claymore mine and communication wires.

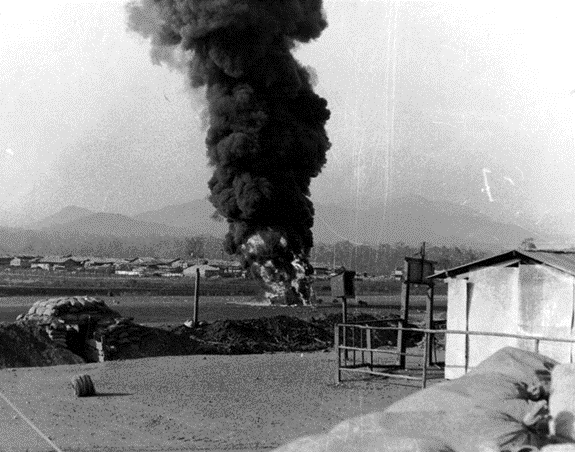

The defenders suffered heavy casualties, but stopped the main assault and killed the infiltrators. The NVA dug in along the hill slopes and grenade-filled trenches where the Mobile Strike Force Soldiers were pinned by machine guns and rocket fire. An NVA flamethrower set the ammunition ablaze, banishing the murky flare-lighted darkness for the rest of the night. Sgt. 1st Class Harold M. Swicegood and the USMC platoon leader, Lt. Adams, were badly wounded and moved to the command bunker. Medic Spec 4 Blomgren reported the CIDG mortar crews had abandoned their weapons. Silva tried to operate the main 4.2-inch mortar but was wounded. At about 5 am, Sgt. Glenn Miller, an A-105 communications specialist, ran to join the Marine howitzer crews, and soon fell after leaving – dead, shot through the head.

The NVA advanced across the eastern side of Ngok Tavak and brought forward more automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenade launchers. In desperation, the defenders called on US Air Force AC-47 “Spooky” gunships to strafe the perimeter and the howitzers, despite the possible presence of friendly wounded in the gun pits. The NVA countered with tear gas, but the wind kept drifting the gas over their own lines. After three attempts, they stopped. A grenade fight between the two forces lasted until dawn.

At daybreak, Australian Warrant Officers Cameron and Lucas, joined by Blomgren, led a CIDG counterattack. The North Vietnamese pulled back under covering fire, and the howitzers were retaken. The Marines fired the last nine shells and spiked the tubes. Later that morning, medical evacuation helicopters supported by covering airstrikes took out the seriously wounded, including Silva and Swicegood. Two CH46s landed 45 replacements from the 12th Mobile Strike Force Company, accompanied by Capt. Euge E. Makowski, but one helicopter was hit in the fuel line and forced down. A rocket hit another helicopter; it fell to the ground in flames, wrecking the small helipad. They placed the remaining wounded aboard a hovering helicopter. As it lifted off, two Mike Force soldiers and 1st Lt. Horace Fleming, one of the stranded aviation crewmen, grabbed the helicopter skids. All three fell to their deaths after the helicopter had reached an altitude of over one hundred feet.

The mobile strike force soldiers were exhausted and nervous. Ammunition and water were nearly exhausted, and Ngok Tavak was still being pounded by sporadic mortar fire. They asked permission to evacuate their positions, but were told to “hold on” as “reinforcements were on the way.” By noon, the defenders decided that aerial reinforcement or evacuation was increasingly unlikely, and night would bring certain destruction. An hour later, they abandoned Ngok Tavak.

Sgt. Thomas Perry, a medic from C Company, arrived at the camp at 5:30 am the morning of the 10th. He cared for the wounded and helped establish a defensive perimeter when they decided to evacuate the camp. As survivors were leaving, Sgt Perry saw Cordell J. Matheney, Jr., standing 20 feet away, as Australian Army Capt. John White formed the withdrawal column at the outer perimeter wire on the eastern Ngok Tavak hillside. They believed Perry was going to join the end of the column.

They hastily piled all the remaining weapons, equipment, and munitions into the command bunker and set it afire. Then, using a LAW, destroyed the grounded helicopter with a ruptured fuel line. Sgt. Miller’s body was not recovered.

After survivors had gone about 1 kilometer, they discovered that Perry was missing. They conducted efforts to locate both Perry and Miller, including a search by a group from Marine Battery D. They were searching along the perimeter when they were hit by enemy grenades and small-arms fire. They never found the men on the team or Perry. Included in this team were Pfc. Thomas Blackman; LCpl. Joseph Cook; Pfc. Paul Czerwonka; LCpl. Thomas Fritsch; Pfc. Barry Hempel; LCpl. Raymond Heyne; Cpl. Gerald King; Pfc. Robert Lopez; Pfc. William McGonigle; LCpl. Donald Mitchell; and LCpl. James Sargent. The remaining survivors evaded through dense jungle to a helicopter pickup point midway to Kham Duc. They completed the extraction shortly before 7 pm on the evening of May 10.

In concert with the Ngok Tavak assault, a heavy mortar and recoilless rifle attack blasted Kham Duc at 2:45 that same morning. Periodic mortar barrages ripped into Kham Duc throughout the rest of the day, while the Americal Division airlifted a reinforced battalion of the 196th Infantry Brigade into the compound. A Special Forces command party also landed, but the situation deteriorated too rapidly for their presence to have a positive effect.

The mortar attack on fog-shrouded Kham Duc resumed on the morning of May 11. The bombardment caused heavy losses among the frightened CIDG soldiers, who fled from their trenches across open ground, seeking shelter in the bunkers. The Army of the Republic of Vietnam Special Forces (LLDB) commander remained hidden. CIDG soldiers refused orders to check the rear of the camp for possible North Vietnamese intruders. That evening, the 11th and 12th Mobile Strike Force companies flew to Da Nang, and half of the 137th CIDG Company from Camp Ha Thanh landed in exchange.

NVA Division, Began Closing the Ring Around Kham Duc

The 1st VC Regiment, 2nd NVA Division, began closing the ring around Kham Duc during the early morning darkness of May 12. Between 4:15 and 4:30 am, the camp and outlying positions came under heavy enemy attack. Outpost 7 fell within a few minutes. Outposts 5, 1, and 3 were reinforced by Americal troops but were in North Vietnamese hands by 9:30 am.

OP1 was manned by Pfc. Harry Coen, Pfc. Andrew Craven, Sgt. Joseph Simpson, and Spec 4 Julius Long from Company E, 2nd of the 1st Infantry. At about 4;15 am, when OP1 came under heavy enemy attack, Pfc. Coen and Spec 4 Long tried to man a 106-millimeter recoilless rifle. Survivors reported that in the initial enemy fire, they were knocked off the bunker. Both men again tried to man the gun again but knocked down a second time by RPG-7 Rocket Launcher fire.

Pfc. Craven, along with two other men, departed the OP1 at 8:30 am on May 12. They moved out 50 yards and could hear the enemy in their last position. At about 11 AM hours, as they were withdrawing to the battalion perimeter, they encountered an enemy position. Craven was the point man and opened fire. The enemy returned fire, and Craven fell with multiple chest wounds. The other two men could not recover him and hastily departed the area. Craven was last seen lying on his back, wounded, near the camp.

OP2 was being manned by 1st Lt. Frederick Ransbottom, Spec 4 Maurice Moore, Pfc. Roy Williams, Pfc. Danny Widmer, Pfc. William Skivington, Pfc. Imlay Widdison, and Spec 5 John Stuller, from the 2nd of the 3rd Infantry, when it came under attack. Informal questioning of survivors from this position stated that Pfc. Widdison and Spec 5 Stuller thought both died during the fight. However, the questioning was not sufficiently thorough to produce enough evidence to confirm their deaths.

The only information available concerning 1st Lt. Ransbottom, Spec 4 Moore, Pfc. Lloyd and Pfc. Skivington that Lt. Ransbottom allegedly radioed Pfc. Winder and Pfc. Williams in the third bunker, and told them he was shooting at the enemy as they entered his bunker.

Spec 4 Juan Jimenez, a rifleman assigned to Company A, 2nd of the 1st Infantry, occupied a defensive position when enemy mortar fire severely wounded him in the back. The Battalion Surgeon declared him dead in the early morning hours of May 12 and then had him carried to the helipad for evacuation. However, because of the situation, space was available in the helicopter for only the wounded, Jimenez’ remains were left behind.

At noon, the NVA launched a massive attack against the main compound. Planes hurling napalm, cluster bomb units, and 750-pound bombs stopped the charge into the final wire barriers. The decision was made by the Americal Division officers to call for immediate extraction.

The evacuation was disorderly and on the verge of complete panic. Enemy fire exploded one of the first extraction helicopters, blocking the airstrip. Engineers of Company A, 70th Engineer Battalion, frantically reassembled one of their dozers (previously torn apart to prevent capture) to clear the runway. The enemy blew eight more aircraft out of the sky.

When Pfc. Richard E. Sands, a member of Company A, 1st Battalion, 46th Infantry, 198th Light Infantry Brigade, was on an extracting CH47 helicopter, 50-caliber machine gun fire hit it at an altitude of 1500-1600 feet shortly after takeoff.

An incoming round caught Sands in the head as he sat near the door gunner. The helicopter made a controlled landing and then caught fire. During the evacuation from the burning helicopter, four personnel and a medic checked Sands and concluded that he died instantly. Because of the danger of incoming mortar rounds and the fire, officers ordered personnel attempting to remove Sands from the helicopter to abandon their attempt. Another helicopter soon landed to evacuate the remaining personnel from the area. Intense antiaircraft fire from the captured outposts caused grave problems. Control over the indigenous forces was difficult. One group of CIDG soldiers had to be held in trenches at gunpoint to prevent them from blocking the runway.

As the evacuation was in progress, members of Company A, 1/46, who insisted on boarding the aircraft first, shoved Vietnamese dependents out of the way. As more Americal infantry tried to clamber into the outbound planes, the outraged Special Forces staff convinced the Air Force to load only civilians on board the C130. They then watched as the civilians pushed children and weaker adults aside.

The crew aboard the U.S. Air Force C130 aircraft were Maj. Bernard Bucher, pilot; Staff Sgt. Frank Hepler, flight engineer; Maj. John McElroy, navigator; 1Lt. Steven Moreland, co-pilot; George Long, load master; Special Forces Capt. Warren Orr and an undetermined number of Vietnamese civilians.

The aircraft reported receiving ground fire on takeoff. The Forward Air Control (FAC) in the area reported that the aircraft exploded in mid-air and crashed in a fireball about one mile from camp. They believed all crew and passengers were dead, as the plane burned quickly, all destroyed except for the tail boom. They could not recover any remains from the aircraft.

U.S. personnel did not positively identify Captain Orr as being aboard the aircraft. He was last seen near it, helping civilians to board. However, a Vietnamese stated he had seen Orr board the aircraft and later positively identified him from a photograph. Rescue efforts were impossible because of the hostile threat in the area.

They gave the order to escape and evade. Spec 4 Julius Long was with Coen and Simpson. All three, wounded, tried to make their way back to the airfield about 350 yards away. As they reached it, they saw the last C130 departing. Coen, shot in the stomach, panicked and started running and shooting his weapon in all directions. Long tried to catch him, but could not. It was the last time he would see Coen. Long then carried Sgt. Simpson to a nearby hill, where they spent the night.

During that night, U.S. aircraft continually strafed and bombed the airfield. Fragments hit Long in the back, and Simpson died later that night. Long left him lying on the hill near the Cam Duc airfield and started his escape and evasion toward Chu Lai. The NVA captured him; releasing him in 1973 from North Vietnam.

Kham Duc was Abandoned to advancing NVA infantry at 4:33 P.m

The Special Forces Command Group was the last organized group out of the camp. As their helicopter soared into the clouds, Kham Duc was abandoned to advancing NVA infantry at 4:33 p.m. on May 12, 1968. The last Special Forces camp on the northwestern frontier of South Vietnam was destroyed.

They conducted two search and recovery operations near OP1 and OP2 and the Cam Duc airfield on July 18, 1970, and August 17, 1970. In these operations, the remains of personnel previously reported missing from this incident were recovered and subsequently identified. They were Spec 5 Bowers, Pfc. Lloyd, Sgt. Sisk, Pfc. Guzman-Rios and Staff Sgt. Carter. Sadly, they couldn’t complete an extensive search and excavation at OP1 and OP2 because of the tactical situation.

The U.S. Government assumed that all the missing at Kham Duc were killed in action until about 1983 when the father of one of the missing men discovered a Marine Corps document showing that four of the men were captured and taken prisoner. The document listed the four by name. Until then, the families were told of the possibility that they took no American prisoners except for Julius Long. A Vietnamese rallier identified the photograph of Roy C. Williams as positively having been a POW.

Until we obtained proof that the rest of the men lost at Ngok Tavak and KHAM Duc are dead, their families will always wonder if they are among those said to still be alive in Southeast Asia.

Editor’s Note: Capt. Warren Orr was from C-Team Headquarters in Da Nang and was sent to Kham Duc to assist in the evacuation of civilians. I was the XO of A-Team 102 and was at the C-Team to conduct some personal business when I ran into Orr as he was preparing to leave for Kam Duc. He was his usual friendly, high-spirited self, but I sensed some apprehension and fear, which is natural when you know you are going to a place where heavy fighting and dying is taking place. Had I been in his shoes, I would have felt the same. When I learned later that he died on a plane loaded with Vietnamese civilians, I felt terrible about his loss.

*****

This article originally appeared on the Together We Served website. The author is the main editor for that website and has contributed many posts (Christy’s Collection) over the years. Here’s the direct link: https://blog.togetherweserved.com/2022/01/21/battle-of-ngok-tavak-kham-duc/

<><><>

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

I thought it was very factual but missed some things that happened. I was there in May of 68.

LikeLike

Bad. Inaccurate. Using discredited sources.

LikeLike

It was excellent reading. Fully enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Hero’s trying to make the best of a very bad situation… To all lost there RIP brothers

LikeLiked by 1 person

The article does not mention the Air Force combat controllers who were attempting to control the evacuation. They had been evacuated but in a colossal screw up were sent back in after everybody else was gone. A C-123 cargo aircraft piloted by Capt Joe Jackson landed under heavy fire to rescue the three AF CCT members as the NVA over ran the camp. Joe Jackson (later a Lt Col. was awarded the Medal of Honor for his action that day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For your consideration Reflections On My Small Part in the Battle of Dai Do Village Republic of South Vietnam April 20-May 4, 1968 My tour of duty in the combat zone of the Republic of South Vietnam began on April 12, 1968 when I arrived in Saigon. After five days of orientation at Headquarters, MACV, I departed for Cua Viet, the northernmost U. S. military post in South Vietnam. Our little base was located on a spit of sand at the mouth of the Cua Viet river which ran parallel to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) five miles to the north. Dong Ha was just a short distance upriver. I was assigned to CTF 543, Task Force Clearwater, to serve as Intelligence Officer. By the time I arrived at Cua Viet I was an experienced intelligence specialist (officer designator 1635). I had 6 years of experience in intelligence work and training in Washington, DC, in Japan, and at the U. S. Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Task Force Clearwater provided security on the Cua Viet River and the Perfume River utilizing various types of river patrol craft, most common of which was the PBR (River Patrol Boat). Task Force Clearwater also had two huge Patrol Air Cushion Vehicles (PACV) located on the Perfume River downriver from Hue.

During my three months at Cua Viet, I participated in numerous patrols on the rivers, in the air and on land with the Navy, the Marine Corps and South Vietnamese Navy (Junk Force). Late April 1968 began one of the most rewarding periods of my naval career. On 24 April I went on a night patrol on a river patrol boat up the river toward Dong Ha. We spotted two unidentified swimmers in the water but were unable to engage them. This was but one of numerous indicators that something big was about to happen on the river. Earlier our little base had begun receiving intense bombardment by North Vietnamese artillery – 85 mm, 122 mm, and the really big ones, 152 mm. These attacks usually occurred at night. The attacks resulted in 6 killed and 23 wounded in a little over two months. I reported these attacks by Flash Precedence message to Navy headquarters in Saigon stating that we were being hit by heavy artillery. Unfortunately, without physical evidence or corroborating evidence, my reports received little attention. In fact, the only answer I got was the speculation that we were being hit by rockets, not artillery. If we were being hit by artillery, that would mean that the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) would have to have moved artillery pieces into the DMZ and that, by definition, was forbidden, so the reasoning went. Therefore, we couldn’t have been hit by artillery fire. After one night attack, an unexploded 152mm artillery round was discovered embedded in the hardpan of our loading area. The Explosive Ordnance Demolition team placed shaped charges on the round and exploded it. I recovered the pieces and put them together like a jigsaw puzzle. Fortunately, the pieces were rather large and easily assembled. I asked my boss for permission to take it to Saigon. He allowed me to take along another man to help carry the heavy round which I had placed in a wooden box. We hitched a ride on a cargo ship to DaNang and caught a ride on a Marine Corps C130 cargo plane to Saigon. We marched into Commander Naval Forces Vietnam offices and placed the artillery round on the desk of the intelligence officer. I said something to the effect that here was proof of what we were being hit with. He stared in disbelief at the huge round on his nice clean desk. I left and went back to Cua Viet.I didn’t hear anything from Saigon about my visit, but a couple of weeks later, a B-52 strike (Arc Light) hit the DMZ. We couldn’t see or hear the airplanes, but we felt the earth shake from the bomb blasts and saw the huge billows of black smoke. We never were hit by artillery again. Shortly after I arrived on 17 April, I began to receive reports from the river patrol boats of increasing activity on the banks of the river. This was significant because there was a dusk-to-dawn curfew in force and because there had previously been little or no activity on the river banks at night. One of our PBRs reported seeing a small group of men on the north bank of the river. When they fired upon the group a fierce firefight resulted. There was a huge explosion on the bank near the men. The men broke off the firefight and fled.A day or two later two LCUs (small landing craft being used to ferry supplies upriver to Dong Ha) came under attack from the north bank of the river. One was hit by a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) resulting in three killed and eight wounded. Based upon these incidents and other indicators I predicted that something of significance was about to happen on or near our river. I just didn’t know what. I reported it up the chain of command.The following day a platoon of Marines was sent to the area of Dai Do Village to investigate the activity I had reported (the firefight and explosion). When the Marines crossed the river they were engaged by a large NVA force. The resulting firefight caused many casualties before they could retreat to the river and escape. In response, a combined force of Marines and ARVN (Army of Vietnam) crossed the river just downriver from Dong Ha. The battle that resulted lasted five days and was the largest ground action of the war up to that time. There were estimated 1500 NVA killed and 500 friendly forces killed. That came to be known as the battle of Dai Do Village. On May 5, after the fighting had died down, I went upriver with an Explosive Ordnance Demolition team to investigate the area near the mouth of a creek near Dai Do Village where our PBR had engaged the group of men in the firefight several nights earlier. We discovered five large anti-ship mines in the reedy shallows a few yards up the creek from the mouth. The mines were approximately 6 feet in length and 24 inches in diameter. We later determined that they were Russian HAT-2 mines. These mines were designed to sink large ships.In addition to the five complete mines, we found parts of a sixth. We concluded that the explosion during the firefight previously mentioned had resulted when an explosive part of that sixth mine had been hit by machine gun fire from our PBR. We also discovered rubber flotation devices designed specifically to support and move the mines into position in the river. The mines were recovered and sent to Saigon for study. The US had not previously seen the HAT-2 mine. We only had intelligence reports with sketches describing the mine and its capabilities.EOD Divers at Cua VietLate on May 5, I received word that the Marines had captured a North Vietnamese sailor that I might be interested in. I traveled to Dong Ha and interrogated the man. He revealed that he had been a member of a North Vietnam Navy special forces team sent across the DMZ to emplace mines in the Cua Viet River.The following day I returned to Dong Ha to further interview the man. I took him to the area on the river where the incident had occurred for an on-the-spot identification and explanation. He described what the team had done and planned to do. Based on the precursor incidents, the battle of Dai Do Village, and the interrogation of the North Vietnamese sailor, as well as the recovery of the HAT-2 anti-ship mines I pieced together the following. North Vietnam intended to invade and capture the northern half of Quang Tri Province as part of what came to be called the May Offensive. The plan called for a North Vietnam Navy special forces team to plant mines in the Cua Viet River just east of Dong Ha near Dai Do Village. The mines were intended to sink a large supply craft as it transited a narrow channel at a bend in the river. This was to occur on or about 1 May.Simultaneously, an NVA regiment was to swoop down and occupy both sides of the river at the site of the sunken boat. They intended to hold the area and prevent supply boats from taking arms and supplies to the Marines and ARVN in Dong Ha. Our PBR force prevented their placing the mines, thus thwarting their plan to sink a boat to block the river. When the Marine platoon went to the area where I had reported the activity on the north bank of the river, they encountered the NVA regiment. Because of the lack of communication between the NVA regiment and their navy special forces mining team, the NVA did not know that the mining of the river had not occurred as planned. Therefore, they marched across the DMZ and met our Marines at Dai Do Village. The result — The Battle of Dai Do Village. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Dai_Do———–The preceding is accurate to the best of my memory and my notes in my personal log covering that time period. Herman Woodrow Hughes CAPTAIN, US NAVY RETIRED

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reflections On My Small Part in the Battle of Dai Do Village

Republic of South Vietnam

April 20-May 4, 1968

My tour of duty in the combat zone of the Republic of South Vietnam began on April 12, 1968 when I arrived in Saigon. After five days of orientation at Headquarters, MACV, I departed for Cua Viet, the northernmost U. S. military post in South Vietnam. Our little base was located on a spit of sand at the mouth of the Cua Viet river which ran parallel to the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) five miles to the north. Dong Ha was just a short distance upriver.

I was assigned to CTF 543, Task Force Clearwater, to serve as Intelligence Officer. By the time I arrived at Cua Viet I was an experienced intelligence specialist (officer designator 1635). I had 6 years of experience in intelligence work and training in Washington, DC, in Japan, and at the U. S. Naval Base, Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Task Force Clearwater provided security on the Cua Viet River and the Perfume River utilizing various types of river patrol craft, most common of which was the PBR (River Patrol Boat). Task Force Clearwater also had two huge Patrol Air Cushion Vehicles (PACV) located on the Perfume River downriver from Hue.

During my three months at Cua Viet, I participated in numerous patrols on the rivers, in the air and on land with the Navy, the Marine Corps and South Vietnamese Navy (Junk Force).

Late April 1968 began one of the most rewarding periods of my naval career. On 24 April I went on a night patrol on a river patrol boat up the river toward Dong Ha. We spotted two unidentified swimmers in the water but were unable to engage them. This was but one of numerous indicators that something big was about to happen on the river.

Earlier our little base had begun receiving intense bombardment by North Vietnamese artillery – 85 mm, 122 mm, and the really big ones, 152 mm. These attacks usually occurred at night. The attacks resulted in 6 killed and 23 wounded in a little over two months.

I reported these attacks by Flash Precedence message to Navy headquarters in Saigon stating that we were being hit by heavy artillery. Unfortunately, without physical evidence or corroborating evidence, my reports received little attention. In fact, the only answer I got was the speculation that we were being hit by rockets, not artillery. If we were being hit by artillery, that would mean that the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) would have to have moved artillery pieces into the DMZ and that, by definition, was forbidden, so the reasoning went. Therefore, we couldn’t have been hit by artillery fire.

After one night attack, an unexploded 152mm artillery round was discovered embedded in the hardpan of our loading area. The Explosive Ordnance Demolition team placed shaped charges on the round and exploded it. I recovered the pieces and put them together like a jigsaw puzzle. Fortunately, the pieces were rather large and easily assembled. I asked my boss for permission to take it to Saigon. He allowed me to take along another man to help carry the heavy round which I had placed in a wooden box.

We hitched a ride on a cargo ship to DaNang and caught a ride on a Marine Corps C130 cargo plane to Saigon. We marched into Commander Naval Forces Vietnam offices and placed the artillery round on the desk of the intelligence officer. I said something to the effect that here was proof of what we were being hit with. He stared in disbelief at the huge round on his nice clean desk. I left and went back to Cua Viet.

I didn’t hear anything from Saigon about my visit, but a couple of weeks later, a B-52 strike (Arc Light) hit the DMZ. We couldn’t see or hear the airplanes, but we felt the earth shake from the bomb blasts and saw the huge billows of black smoke. We never were hit by artillery again.

Shortly after I arrived on 17 April, I began to receive reports from the river patrol boats of increasing activity on the banks of the river. This was significant because there was a dusk-to-dawn curfew in force and because there had previously been little or no activity on the river banks at night. One of our PBRs reported seeing a small group of men on the north bank of the river. When they fired upon the group a fierce firefight resulted. There was a huge explosion on the bank near the men. The men broke off the firefight and fled.

A day or two later two LCUs (small landing craft being used to ferry supplies upriver to Dong Ha) came under attack from the north bank of the river. One was hit by a rocket propelled grenade (RPG) resulting in three killed and eight wounded.

Based upon these incidents and other indicators I predicted that something of significance was about to happen on or near our river. I just didn’t know what. I reported it up the chain of command.

The following day a platoon of Marines was sent to the area of Dai Do Village to investigate the activity I had reported (the firefight and explosion). When the Marines crossed the river they were engaged by a large NVA force. The resulting firefight caused many casualties before they could retreat to the river and escape. In response, a combined force of Marines and ARVN (Army of Vietnam) crossed the river just downriver from Dong Ha. The battle that resulted lasted five days and was the largest ground action of the war up to that time. There were estimated 1500 NVA killed and 500 friendly forces killed. That came to be known as the battle of Dai Do Village.

On May 5, after the fighting had died down, I went upriver with an Explosive Ordnance Demolition team to investigate the area near the mouth of a creek near Dai Do Village where our PBR had engaged the group of men in the firefight several nights earlier. We discovered five large anti-ship mines in the reedy shallows a few yards up the creek from the mouth. The mines were approximately 6 feet in length and 24 inches in diameter. We later determined that they were Russian HAT-2 mines. These mines were designed to sink large ships.

In addition to the five complete mines, we found parts of a sixth. We concluded that the explosion during the firefight previously mentioned had resulted when an explosive part of that sixth mine had been hit by machine gun fire from our PBR. We also discovered rubber flotation devices designed specifically to support and move the mines into position in the river. The mines were recovered and sent to Saigon for study. The US had not previously seen the HAT-2 mine. We only had intelligence reports with sketches describing the mine and its capabilities.

Late on May 5, I received word that the Marines had captured a North Vietnamese sailor that I might be interested in. I traveled to Dong Ha and interrogated the man. He revealed that he had been a member of a North Vietnam Navy special forces team sent across the DMZ to emplace mines in the Cua Viet River.

The following day I returned to Dong Ha to further interview the man. I took him to the area on the river where the incident had occurred for an on-the-spot identification and explanation. He described what the team had done and planned to do.

Based on the precursor incidents, the battle of Dai Do Village, and the interrogation of the North Vietnamese sailor, as well as the recovery of the HAT-2 anti-ship mines I pieced together the following.

North Vietnam intended to invade and capture the northern half of Quang Tri Province as part of what came to be called the May Offensive. The plan called for a North Vietnam Navy special forces team to plant mines in the Cua Viet River just east of Dong Ha near Dai Do Village. The mines were intended to sink a large supply craft as it transited a narrow channel at a bend in the river. This was to occur on or about 1 May.

Simultaneously, an NVA regiment was to swoop down and occupy both sides of the river at the site of the sunken boat. They intended to hold the area and prevent supply boats from taking arms and supplies to the Marines and ARVN in Dong Ha. Our PBR force prevented their placing the mines, thus thwarting their plan to sink a boat to block the river.

When the Marine platoon went to the area where I had reported the activity on the north bank of the river, they encountered the NVA regiment. Because of the lack of communication between the NVA regiment and their navy special forces mining team, the NVA did not know that the mining of the river had not occurred as planned. Therefore, they marched across the DMZ and met our Marines at Dai Do Village. The result — The Battle of Dai Do Village.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Dai_Do

———–

The preceding is accurate to the best of my memory and my notes in my personal log covering that time period.

Pertinent photos will be furnished upon request

Herman Woodrow Hughes

CAPTAIN, US NAVY RETIRED

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, sir, for your account of this battle. You might also be interested in another article featuring those who were awarded the MOH. There are two videos in that article relating to the battle of Dai Do.

LikeLike

A Note from The Virtual Wall

”

1st Lt Horace H. Fleming was the pilot of a CH-46A (BuNo 151907) bringing reinforcements into the strongpoint of Ngok Tavak, about five miles distant from the border outpost at Kham Duc. Ngok Tavak had been attacked by elements of the NVA 2nd Regiment in the early morning hours of 10 May 1968, and by the time the two CH-46s arrived the camp was undering heavy rocket, mortar, and infantry attack. As Fleming lifted off, his aircraft was hit by enemy antiaircraft fire, severing a fuel or oil line (different accounts vary) and forcing him to land within the beseiged compound. As a second aircraft, a UH-1 Huey, hovered over the fouled landing pad in order to take on wounded, Fleming and one or two Nung soldiers mounted the skids but were unable to enter the crowded cabin. After the aircraft lifted off Fleming and the Nung(s) fell to their deaths in the NVA-controlled area outside the defensive perimeter.

“The Ngok Tavak defenders withdrew to the base camp at Kham Duc, arriving just in time to fight in the unsuccessful defense of that camp. 1st Lt Fleming is one of at least 39 Americans who died during the defeats at Ngok Tavak and Kham Duc, and one of the 32 whose remains have not been repatriated.” – copied from The Virtual Wall

LikeLike

Met a guy around 2003 who said he was at Ngok Tavak and escaped into the jungle with another guy. They made their way to the end of the airstrip at Kham Duc. I was an engineer at Kham Duc at this time. Several of us volunteered to go down the airstrip and pick up survivors. When we got there we waited a few minutes, no one was there and returned to the camp. It wasn’t until 2003 when I found out after this guy from Ngok Travak told me he was one of the guys waiting for us. He said Kham Duc was in more trouble than they were and decided to take their chances and wait to be extracted. We, the engineers were supposed to get on that first C130 that landed. We were waiting in the trenches closest to the airstrip. We were told the plane will land, go down the runway, turn around and come back preparing for a take off. The plane would not stop. It was taxing down the run way and when given the signal we were told to run on the airstrip and jump onto the opened

tail gate of the plane. When given the okay we were supposed to run toward the runway, and jump into the moving plane but before we knew it there were Vietnamese villagers and many other Vietnamese soldiers also trying to do the same thing. We were nudged out as they had the jump on us. Thank God this was the plane that was shot down apron taking off. It crashed not far from there. We believed we were going to die there, but a few hours we were told another C 130 was coming to try the same thing. This time we were lucky to get on the plane. Very one was quietly praying we did not meet him he fate of the first plane. We then were flown to Danang. All of this took place in the late afternoon on May 12 1968. I have another story to tell about another incident that happened a few days before the evacuation, but that’s another story.

LikeLike

The Battle of Ngok Tavak is written by Bruce Davies.

LikeLike

I’m intimately familiar with both these battles, the survivors and some families of those who perished. The book, “ The Battle of Ngoc Tavak “ is an excellent and accurate read. If ever there was hell on earth.

LikeLike

What a terrible battle!

LikeLike

Toughest of times!

LikeLike

Test

LikeLike

Talk about Holy Hell….

LikeLike

“VIETNAM BEYOND”by Gerald E. Augustine now availab

LikeLike

RIP Lest we forget.

LikeLike