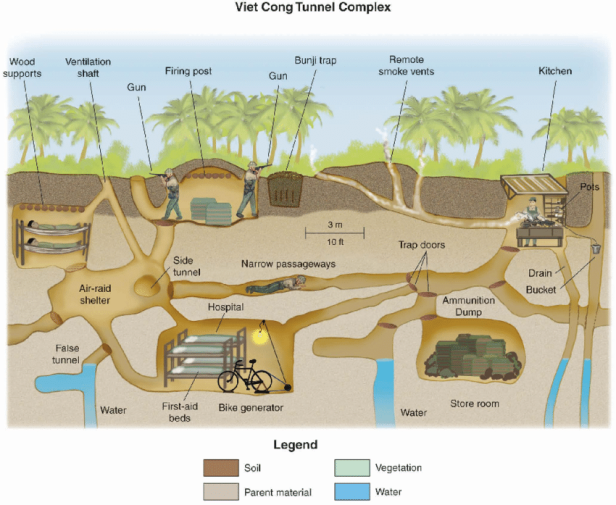

The tunnels were used by Viet Cong soldiers as hiding spots during combat, as well as serving as communication and supply routes, hospitals, food and weapon caches, and living quarters for numerous North Vietnamese fighters.

And while U.S. forces were establishing a foothold and then hunting down Viet Cong elements, the Viet Cong were digging literally hundreds of miles of tunnels that they could use to safely store supplies, move across the battlefield in secret, and even stage ambushes against U.S. troops. Read more here:

<><><>

In order to combat better-supplied American and South Vietnamese forces during the Vietnam War, Communist guerrilla troops known as the Viet Cong (VC) dug tens of thousands of miles of tunnels, including an extensive network running underneath the Cu Chi district northwest of Saigon. Soldiers used these underground routes to house troops, transport communications and supplies, lay booby traps, and mount surprise attacks, after which they could disappear underground to safety. To combat these guerrilla tactics, U.S. and South Vietnamese forces trained soldiers known as “tunnel rats” to navigate the tunnels in order to detect booby traps and enemy troop presence. Now part of a Vietnam War memorial park in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon), the Cu Chi tunnels have become a popular tourist attraction.

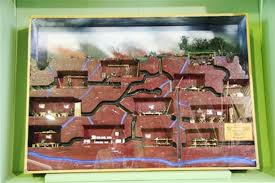

Communist forces began digging a network of tunnels under the jungle terrain of South Vietnam in the late 1940s, during their war of independence from French colonial authority. Tunnels were often dug by hand, only a short distance at a time. As the United States increasingly escalated its military presence in Vietnam in support of a non-Communist regime in South Vietnam beginning in the early 1960s, North Vietnamese and Viet Cong troops (as Communist supporters in South Vietnam were known) gradually expanded the tunnels. At its peak during the Vietnam War, the network of tunnels in the Cu Chi district linked VC support bases over a distance of some 250 kilometers, from the outskirts of Saigon all the way to the Cambodian border.

When the first spades sank into the earth around Cu Chi, the region was covered by a rubber plantation tied to a French tire company. Anti-colonial Viet Minh dug the first Vietnamese tunnels here in the late 1940s; intended primarily for storing arms, they soon became valuable hiding places for the resistance fighters themselves. Over a decade later, VC activists controlling this staunchly antigovernmental area, many being local villagers, followed suit and went to ground. By 1965, 250km of tunnels crisscrossed Cu Chi and surrounding areas – just across the Saigon River was the notorious guerrilla power base known as the Iron Triangle – making it possible for the VC guerrilla cells in the area to link up with each other and to infiltrate Saigon at will. One section daringly ran underneath the Americans’ Cu Chi Army Base.

Though the region’s compacted red clay was perfectly suited to tunneling and lay above the water level of the Saigon River, the digging parties faced a multitude of problems. Quite apart from the snakes and scorpions they encountered as they labored with their hoes and crowbars, there was the problem of inconspicuously disposing of the soil by spreading it in bomb craters or scattering it in the river under cover of darkness. With a tunnel dug, ceilings had to be shored up, and as American bombing made timber scarce the tunnellers had to resort to stealing iron fence posts from enemy bases. Tunnels could be as small as 32″ wide and 32″ high and were sometimes four levels deep; vent shafts (to disperse smoke and aromas from underground ovens) were camouflaged by thick grass and termites’ nests. In order to throw the Americans’ dogs off the scent, pepper was sprinkled around vents, and sometimes the VC even washed with the same scented soap used by GIs.

Did you know? “Tunnel rats,” as American soldiers who worked in the Cu Chi tunnels during the Vietnam War were known, used the evocative term “black echo” to describe the experience of being in the tunnels.

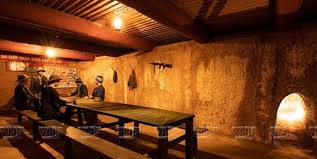

As the United States relied heavily on aerial bombing, North Vietnamese and VC troops went underground in order to survive and continue their guerrilla tactics against the much better-supplied enemy. In heavily bombed areas, people spent much of their life underground, and the Cu Chi tunnels grew to house entire underground villages, in effect, with living quarters, kitchens, ordnance factories, hospitals, and bomb shelters. In some areas, there were even large theaters and music halls to provide a diversion for the troops (many of them peasants) and their supporters.

In addition to providing underground shelter, the tunnels served a key role during combat operations, including as a base for Communist attacks against nearby Saigon. VC soldiers lurking in the tunnels set numerous booby traps for U.S. and South Vietnamese infantrymen, planting trip wires that would set off grenades or overturn boxes of scorpions or poisonous snakes onto the heads of enemy troops. To combat these guerrilla tactics, U.S. forces would eventually train some soldiers to function as so-called “tunnel rats.” These soldiers (usually of small stature) would spend hours navigating the cramped, dark tunnels to detect booby traps and scout for enemy troops.

In January 1966, some 8,000 U.S. and Australian troops attempted to sweep the Cu Chi district in a large-scale program of attacks dubbed Operation Crimp. After B-52 bombers dropped a large number of explosives onto the jungle region, the troops searched the area for enemy activity but were largely unsuccessful, as most Communist forces had disappeared into the network of underground tunnels. A year later, around 30,000 American troops launched Operation Cedar Falls, attacking the Communist stronghold of Binh Duong province north of Saigon near the Cambodian border (an area known as the Iron Triangle) after hearing reports of a network of enemy tunnels there.

After bombing attacks and the defoliation of rice fields and surrounding jungle areas with powerful herbicides, U.S. tanks and bulldozers moved in to sweep the tunnels, driving out several thousand residents, many of them civilian refugees. North Vietnamese and VC troops slipped back within months of the sweep, and in early 1968 they would use the tunnels as a stronghold in their assault against Saigon during the Tet Offensive.

During the American War, the villages around the district of Cu Chi supported a substantial Viet Cong (VC) presence. Faced with American attempts to neutralize them, they quite literally dug themselves out of harm’s way, and the legendary Cu Chi tunnels were the result.

In the early 60s, the ruling democratic regime patrolled mostly on the large roads and through cities because their heavy vehicles had trouble penetrating the jungles or making it up mountains.

By the time the U.S. deployed troops to directly intervene, regime forces had been overrun in multiple locations and had a firm foothold across large patches of the jungle, hills, and villages.

American attempts to flush out the Vietnamese tunnels proved ineffective. Operating out of huge bases erected around Saigon in the mid-Sixties, they evacuated villagers into strategic hamlets and then used defoliant sprays and bulldozers to rob the VC of cover, in “scorched earth” operations such as January 1967’s Cedar Falls. Even then, tunnels were rarely effectively destroyed – one soldier at the time compared the task to “fill[ing] the Grand Canyon with a pitchfork”. GIs would lob down gas or grenades or else go down themselves, armed only with a flashlight, a knife, and pistol. Die-hard soldiers who specialized in these underground raids came to be known as tunnel rats, their unofficial insignia “Insigni Non Gratum Anus Rodentum”, meaning “not worth a rat’s ass”. Booby-traps made of sharpened bamboo stakes awaited them in the dark, as well as “bombs” made from Coke cans and dud bullets found on the surface. Tunnels were low and narrow, and entrances so small that GIs often couldn’t get down them, even if they could locate them. Maverick war correspondent Wilfred Burchett, traveling with the NLF in 1964, found his Western girth a distinct impediment: “On another occasion, I got stuck passing from one tunnel section to another. In what seemed a dead end, a rectangular plug was pulled out from the other side, and, with some ahead pulling my arms and some pushing my buttocks from behind, I managed to get through “I was transferred to another tunnel entrance built especially to accommodate a bulky unit cook.”

Another American tactic aimed at weakening the resolve of the VC guerrillas involved dropping leaflets and broadcasting bulletins that played on the fighters’ fears and loneliness. Although this prompted numerous desertions, the tunnellers were still able to mastermind the Tet Offensive of 1968. Ultimately, the Americans resorted to more strong-arm tactics to neutralize the tunnels, sending in the B52s freed by the cessation of bombing of the North in 1968 to level the district with carpet bombing. The VC’s infrastructure was decimated by Tet, and further weakened by the Phoenix Program. By this time, though, the tunnels had played their part in proving to America that the war was unwinnable. At least 45,000 Vietnamese men and women guerrillas and sympathizers are thought to have perished here during the American War, and the terrain was laid waste – pockmarked by bomb craters, devoid of vegetation, the air poisoned by lingering fumes.

Cu Chi tunnels, Vietnam © daphnusia/Shutterstock

Living conditions below ground were appalling for these “human moles”. The tunnels were foul-smelling and became so hot by the afternoon that inhabitants had to lie on the floor in order to get enough oxygen to breathe. The darkness was absolute, and some long-term dwellers suffered temporary blindness when they emerged into the light. At times it was necessary to stay below ground for weeks on end, alongside bats, rats, snakes, scorpions, centipedes, and fire ants. Some of these unwelcome guests were co-opted to the cause: boxes full of scorpions and hollow bamboo sticks containing vipers were secreted in tunnels, where GIs might unwittingly knock them over.

Within the multi-level tunnel complexes, there were latrines, wells, meeting rooms, and dorms. Rudimentary hospitals were also scratched out of the soil. Operations were carried out by torchlight using instruments fashioned from shards of ordnance, and a patient’s own blood was caught in bottles and then pumped straight back using a bicycle pump and a length of rubber hosing. Such medical supplies as existed were secured by bribing ARVN soldiers in Saigon. Doctors also administered herbs and acupuncture – even honey was used for its antiseptic properties. Kitchens cooked whatever the tunnellers could get their hands on.

With rice and fruit crops destroyed, the diet consisted largely of tapioca, leaves, and roots, at least until enough bomb fragments could be transported to Saigon and sold as scrap to buy food. Morale was maintained in part by performing troupes that toured the tunnels, though songs like “He who comes to Cu Chi, the Bronze Fortress in the Land of Iron, will count the crimes accumulated by the Enemy” were not quite up to the standard set by Bob Hope as he entertained the US troops.

Cu Chi Tunnel, Vietnam © daphnusia/Shutterstock

There were hundreds of miles of tunnels, and most of them were nearly impossible to find. Meanwhile, many tunnel networks had hidden chambers and pathways within them. So, even if you found a tunnel network and began to destroy it, there was always a chance that you missed a branch or two and the insurgents will keep using the rest of it after you leave.

Today, tourists can visit a short stretch of the tunnels, drop to their hands and knees and squeeze underground for an insight into life as a tunnel-dwelling resistance fighter. Some sections of the tunnels have been widened to allow passage for the fuller frame of Westerners but it’s still a dark, sweaty, claustrophobic experience, and not one you should rush into unless you’re confident you won’t suffer a subterranean freak-out.

In the years following the fall of Saigon in 1975, the Vietnamese government preserved the Cu Chi tunnels and included them in a network of war memorial parks around the country.

*****

From admin: I’ve included a 41-page slide presentation here summarizing the tunnels in Vietnam; it also includes additional information beyond what was presented here in the article. Click below:

https://web.mst.edu/~rogersda/umrcourses/ge342/Cu%20Chi%20Tunnels-revised.pdf

Additionally, I’ve added a 16-minute video highlighting the tunnels in Cu Chi. Join this couple who take us on a guided tour of the complex:

<><><>

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occurs on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance.

My UNCLE by marriage was BOB BATTEN

Tunnel rat at chu chi

LikeLike

The big tunnels were the exception and not the rule I have a lot of tunnel experiences

LikeLike

I had a detach ment of 11 men we did nothing but seek intelligence on the the tunnels. We had a big room with a map of all the tunnels of south Vietnam and identified as to their use I wrote a manual explaining how they were booby trapped I went back to the tunnels in 1996

LikeLike

Brings back alot of memories was in the 25th infantry in 1969. We worked along the Cambodia border doing night ambushes. Cu Chi & Tay Nin our unit came across many tunnel entrance but didn’t have any tunnel rats in our unit so mostly dropped grenades in the hole! Great article very informative .

LikeLike

I wasn’t exposed to the tunnels when I was stationed in the Hue area in 68-69. My brother was a KIA in the Cu Chi area in early 1970 in a ambush which came out of the tunnels you described.

LikeLike

We always think of big elaborate tunnels like those at Chu Chi, but there were many much smaller ones. After we popped an ambush outside Phouc Vinh I tried to follow a fresh trail into one by the Song Be River that was so small that I got stuck about 20 feet down, even though I had no weapon and only weighed about 150. I decide that whoever was there could stay there and finally wriggled my way out uphill and backwards.

LikeLike

I served in combat with 196th L.I.B. and 4th I.D. 2/12th 1965-1967. Tay Ninh and Dau Tieng.

My book “VIETNAM BEYOND has just been published. on amazon or at 800 788-7654 m-f – 9-5..

I was there!!!!!

LikeLike

It was very good, my base camp was Cuchi 25th Division Armor. We would go out on patrol and we would come across a Tunnel complex and send down a Tunnel Rat, it took a toll on him after a while. This other unit sent a trooper in a tunnel and we heard a little noise and the ground heaved up he didn’t make it, he hit a booby trap, things happened in Vietnam and the American people had no idea what we, the Soldiers went through.

LikeLike

Do you respond to questions?

________________________________

LikeLike

Where did they get the electric from? God Bless you guys.

LikeLike

Golf 2/1 1st Marines 2nd platoon Sierra Squad Nam Grunt, tunnel rat my whole tour February 69 to February 70. Amazing what I found, small tunnels to warehouse size.

LikeLike

Very informative, served 68/69!

LikeLike

Stationed at FB Lanyard & Pace west of Tay NInh on Cambodian boarder. 23rd Artillery Group, 2/32nd

LikeLike

I served with B 2/12 Inf; 25th Inf. Jan. 69- Jan 70, seen these tunnels, one time by the HoBo Woods, 1st week in June one VC came up and began firing hitting my pant leg and shooting him in the back, we were able to thro a grand into the hole, web gear, body parts flew out of the tunnel.

LikeLike

Excellent information shared and appreciated by this veteran. Had no idea of the amount or intensity of tunnels we were up against. Thanks much. 2/22nd Mech 25th Inf Div. 69-70.

LikeLike

Randy I feel the same we were at Cu Chi , we shared a hootch at fsb Wood,

LikeLike

Randy Bill Blom

LikeLike

Impressive. I was a lieutenant in the 1st Division in 1966-67, and I vividly recall Cedar Falls, when I ran a number of ammo and supply convoys to Cu Chi, as well as the people taken out of the Iron Triangle to be resettled.

LikeLike

This to cherriesWriter; pdoggbiker: All Hail! I am line medic who seems to have an e-ddress herein: ‘my medic campgrounds’tagline: gunga Din syndrome! It’s a curse! but when I tried to edit same, to be a better ‘fit’, I got frozen on a blank ‘page 3’.Don’t know if my ‘comment’ was enabled to be received today, to this OUTSTANDING article. To the effect that — the humble trenching tool I took home as souvenir, end of ’68, was to me the Weapon that Won Victor & Nguyen of North — that war; over Buff and Puff even!

LikeLike

Good article. Served with the 1st Inf. stationed at firebase near NUi Ba Den. I crawled into several but never saw any large ones. We searched tunnels that only allowed us to move on hands and knees. Found a makeshift press type equipment and a few small VC pamphlets among other things. Last one had some inhabitants in an upper level so we didn’t stay for dinner. My partner and I didn’t we could crawl backwards so fast. Tunnel was blown up.

LikeLike

I have several aerial pics of Nui Ba Dinh mountain and Firebase I took from Huey. Send e-mail addr if you’d like them

LikeLike

My Vietnam Vet husband spoke of the tunnels often. He was Army attached to Marines field artillery wireman. He passed 6 yrs ago AO

LikeLike

I was a radio operator in Marine Wing Support Group – 17, based in Danang, March 69 to January 70. Not long before I left, there was a rumor that the VC were digging tunnels underneath the Danang airstrip. I never knew whether that was true but it did make this short-timer nervous about getting home. Semper Fi, Joe Benson

LikeLike

to big to be a “tunnel rat” Always support them in any thing they did. Crazy is the word I hung on to, but BRAVE is the best descrition.

LikeLike