This article is the result of reader comments following my past article, “12 Major Battles of the Vietnam War.” https://cherrieswriter.wordpress.com/2017/01/03/12-major-battles-of-the-vietnam-war/

There were many comments split between my Vietnam Facebook groups and following the posted article that challenged the word “Major” insisting that anytime participants were fired upon and placed in harms’ way, then in their minds, it wasn’t just a skirmish, ambush or sniper – to them, it was a major experience. Personally, I never knew the names of any of the Operations or battles that I had participated in. All I know is when the shooting started, it was a battle; doesn’t matter if it lasted five minutes or sporadically for a month.

I’ve listed those battles mentioned from your comments along with notes and pictures about each one. Due to its size, (31,000 words and 136 pages) – the equivalent of a short novel, I split the article into 3 parts so the page loads faster. I’ve added as much detail as possible to see the “big picture” and hope it meets with your approval. I also hope that readers find this article educational and learn more about the Vietnam War from the information provided. Kudos to anyone able to read the entire article in one setting!

Note that these engagements are neither listed chronologically nor are they in order of importance. They are only suggestions deemed important to mention from my readers. They are also posted in the order that I recorded them from your notes:

Part I

Operation Prairie I-IV

Battle of Con Tien

Battle of Dong Ha

Operation Allen Brook

Operation Hump

Battle of An Loc

Operation Lam Son 719

Part II

Battle of Quang Tri Province

Battle of Ben Het Special Forces Camp

Battle of Binh Ghia

The Hill Fights

Battle of Trang Bang

Battle of Tam Quang

Part III

Operation Cedar Falls

Operation Dewey Canyon

The Cambodian Campaign

Attack on FSB Jay

Attack on FSB Illingworth

Battle of Ap Gu

Operation Prairie I

This was a U.S. military operation in northern South Vietnam that sought to eliminate North Vietnamese Army (NVA) forces south of the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ).Over the course of late 1965 and early 1966 the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) intensified its military threat along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The tactical goal of these incursions across the 17th Parallel sought to draw United States Military forces away from populated cities and towns, a similar strategy would be employed during the final months of 1967 in order to maximize the impact of the upcoming Tet Offensive. In response, the Marines elected to construct and reinforce a string of firebases due south of the DMZ including installments at Con Thien, Gio Linh, Camp Carroll, and Dong Ha. To support the defense of the DMZ area, Marines were often relocated from the southern regions of I Corps. In addition to these firebases, U.S. forces also established an interconnected sequence of electronic sensors and other detection devices called the McNamara Line.

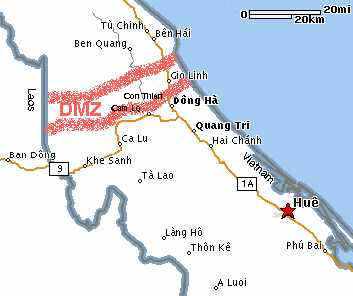

Map of the demilitarized zone and northern Quang Tri Province during the Vietnam War

The original actions in defense of the Vietnamese DMZ, officially designated as Operation Hastings, began on 15 July 1966. Operation Hastings was a strategic success for American and South Vietnamese troops as the estimated enemy casualties reached upwards of 800 enemy soldiers. The operation, however, was only scheduled to last slightly longer than three weeks reaching its conclusion on 3 August 1966.

Due to the initial, albeit brief, successes of Operation Hastings the United States elected to essentially renew the mission and rename it, Operation Prairie. Operation Prairie would cover the exact same areas along the DMZ that Operation Hastings had, as well as had the same mission. The formal objective of Prairie was to search the areas south of DMZ for NVA troops and eliminate them. Another purpose of Operation Prairie aimed to determine the extent of NVA and VC infiltration of northern I Corps, the area of South Vietnam stretching from the northern edge of the Central Highlands to the DMZ.

.

Over the course of the next few hours Major Vincil W. Hazelbaker landed his UH-1E helicopter under withering enemy fire to resupply the Marines. Hazelbaker then departed, reloaded his helicopter at Dong Ha Airfield, and bravely returned. After several unsuccessful landing attempts Hazelbaker finally safely landed on the ground, resupplied the troops a second time, however during the unloading of ammunition an enemy rocket impacted the rotor mast, crippling the aircraft. Hazelbaker then assumed command, as Captain Lee had been injured by a fragmentation grenade, and directed a napalm strike on the enemy position at dawn on 9 August 1966. Reinforcements finally arrived later that morning, secured the area, and aided in the evacuation of the remaining Marines in the afternoon. In total Team Groucho Marx and their reinforcements suffered thirty-two casualties, with five men killed, while they inflicted at least thirty-seven enemy KIAs (a support team later noted other bloodstains and drag marks indicating a much larger higher number of casualties). For the valiant actions occurring during the two-day fight, Captain Howard V. Lee earned the Medal of Honor and Major Vincil W. Hazelbaker was presented the Navy Cross.

On 15 September 1966, an additional 1,500 Marines landed from 7th Fleet ships off Quang Tri province to support two companies of the 4th Marine Regiment who were pinned down by a large force of NVA troops. The outnumbered American forces were unable to break out until 18 September 1966. Operation Prairie concluded on 31 January 1967 with a total of 1,397 known enemy casualties.

Operation Prairie II

The allied forces renewed the operation several times during the first half of 1967 beginning with Operation Prairie II, which spanned from 1 February to 18 March and accounted for a total of 693 enemy casualties.

Operation Prairie III

Operation Prairie III began just two days after the conclusion of Prairie II on 20 March and lasted until 19 April 1967 with an enemy casualties estimated at 250 soldiers.

Operation Prairie IV

Operation Prairie IV ran from 20 April to 17 May 1967 and featured heavy fighting east of Khe Sanh along the southern banks of the Ben Hai River, including five battalions of the 1st Division of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) and three battalions of Marines and the Special Landing Force. By the time Prairie IV wrapped up actions, a total of 164 American troops had been killed with approximately 999 wounded, while the NVA suffered 505 deaths with an unknown number of wounded.

Operation Prairie was undoubtedly a huge success for the American and South Vietnamese forces, however, its primary triumphs were overshadowed in the months and years that followed. The allied forces accomplished exactly what had been outlined in Prairie’s objectives: prevent enemy infiltration across the DMZ and Ben Hai River and determine the extent of their infiltration. Nevertheless, the NVA units merely fled over the DMZ to North Vietnam in order to regroup, re-equip, and then reenter South Vietnam later in 1967. One of the other purposes of Operation Prairie was to reduce the large investment of manpower that the U.S. forces had committed to protect the DMZ. Instead, the NVA strategy tied down a major portion of the Marine force in I Corps along the vast, barren tracts of land south of the DMZ, leaving population centers undermanned and under protected.

Battle of Con Tien

This battle occurred during Operation Prairie I and is included in the information above. Therefore, I’ve added a 25 minute documentary to tell this story.

Battle at Dong Ha

In the spring of 1968, after the Tet Offensive and before the opening of the Paris peace talks, the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and Vietcong made a determined effort to improve their bargaining position. They conducted 119 attacks on provincial and district capitals, military installations, and major cities in South Vietnam. The United States Marines maintained a supply base at Dong Ha in I Corps.

It was in the northeastern area of Quang Tri Province. Late in April and early in May, the NVA 320th Division, with 8,000 troops, attacked Dong Ha and fought a rigorous battle against an allied force of 5,000 marines and South Vietnamese soldiers. The North Vietnamese failed to destroy the supply base and had to retreat back across the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), leaving behind 856 dead. Sixty-eight Americans died in the fighting.

Operation Allen Brook

This was a US Marine Corps operation that took place south of Danang, lasting from 4 May to 24 August 1968.

Go Noi Island was located approximately 25 km south of Danang to the west of Highway 1, together with the area directly north of the island, nicknamed Dodge City by the Marines due to frequent ambushes and firefights there, it was a Vietcong and People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) stronghold and base area. While the island was relatively flat, the small hamlets on the island were linked by hedgerows and concealed paths providing a strong defensive network. Go Noi was the base for the Vietcong’s Group 44 headquarters for Quảng Nam Province, the R-20 and V-25 Battalions and the T-3 Sapper Battalion and, it was believed, elements of the PAVN 2nd Division.

On the morning of 4 May 1968 two Companies of the 2nd Battalion 7th Marines supported by tanks crossed the Liberty Bridge onto the island meeting only light resistance for the first few days. On 7 May Company A 1st Battalion 7th Marines relieved one Company from 2/7 Marines and Company K 3/7 Marines was added to the operation. By 8 May the Marines had lost 9 killed and 57 wounded and the Vietcong 88 killed. On the evening of 9 May the Marines encountered heavy resistance at the hamlet of Xuan Dai, after calling in air strikes the Marines overran the hamlet resulting in 80 PAVN killed.

On 13 May Company I 3rd Battalion 27th Marines was deployed to the Que Son mountains southwest of Go Noi moving east onto the island and the Marines on the island began sweeping west linking up at the Liberty Bridge on 15 May. Company E 2/7 Marines and the command group were airlifted out of the area on the evening of 15 May.

The Marines then began a deception plan crossing the Liberty Bridge as if the operation had concluded and then crossing back onto the island on the early morning of 16 May. At 09:00 on 16 May 3/7 Marines encountered a PAVN Battalion at the hamlet of Phu Dong, the Marines were unable to outflank the PAVN and called in air and artillery support as the battle continued all day. By nightfall the PAVN abandoned their positions leaving more than 130 dead while Marine losses were 25 dead and 38 wounded. The hamlet was found to contain a PAVN Regimental headquarters and vast quantities of supplies.

On the morning of 17 May 3/7 Marines moved out of Phu Dong patrolling southeast. Company I 3/27 Marines was leading the column when it was ambushed by a strongly entrenched PAVN force near the hamlet of Le Nam. The other Marine Companies attempted to assist Company I but the PAVN defenses proved too strong and artillery support was the only way to relieve the pressure on Company I. It was decided that Companies K and L 3/27 Marines would air assault into the area and the first helicopters landed at 15:00 and Company K broke through to relieve Company I at 19:30 while the PAVN withdrew. Marine losses were 39 dead and 105 wounded while PAVN losses were 81 killed. PFC Robert C. Burke a machine-gunner in Company I would be posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions during the battle.

On 18 May 3rd Battalion 5th Marines replaced 3/7 Marines and operational control passed to 3/27 Marines. At 09:30 the Marines began taking sniper fire from the hamlet of Le Bac (2). Companies K and L were sent to clear out the snipers but were quickly pinned down by another well-prepared PAVN ambush. Airstrikes and artillery fire was called in but due to the proximity of the opposing forces were of limited effect. At 15:00 Company M 3/27 Marines arrived by helicopter to replace Company L and cover the retreat of Company K and air and artillery strikes were directed against Le Bac (2). Marine losses were 15 killed, 35 wounded and over 90 cases of heat exhaustion while PAVN losses were 20 killed.

For the next 6 days the Marines continued patrolling, suffering frequent ambushes despite strong preparatory fires. The Marines altered their tactics so that when the enemy was encountered they would hold their positions or pull back to allow air and artillery to deal with the entrenched forces. From 24–27 May a sustained fight took place at the hamlet of Le Bac (1), only ending when torrential rain made further fighting impossible. By the end of May total casualties for the battle were 138 Marines killed and 686 wounded while PAVN/Vietcong losses exceeded 600 killed.

On 26 May the 1st Battalion 26th Marines reinforced the operation, while on the 28th 3/27 Marines was relieved by 1st Battalion 27th Marines and 3/5 Marines was returned to the Division reserve. During early June the 1/26 and 1/27 Marines carried out ongoing search and clear operations on the island with regular ambushes by small PAVN/Vietcong forces.

On 5 June as the Marine Battalions moved west along the island they were ambushed by a PAVN force at the hamlet of Cu Ban (3), due the proximity of the enemy forces supporting fire was ineffective and a confused close-quarters battle raged throughout the day until tanks allowed the Marines to overrun the enemy positions. Marines losses were 7 killed and 55 wounded while PAVN losses were 30 killed.

On 6 June 1/26 Marines was withdrawn from the operation and elements of the 1st Engineer Battalion arrived with orders to destroy the fortifications on Go Noi with 1/27 Marines providing security. On the early morning of 15 June a PAVN force attacked Company B 1/17 Marines’ night defensive position, the attack was defeated with 21 PAVN killed with no Marine losses.

On 19 June Companies B and D were ambushed by the PAVN at the hamlet of Bac Dong Ban, the fight lasted 9 hours before the Marines were able to overrun the PAVN bunkers. Marine losses were 6 killed and 19 wounded while the PAVN lost 17 killed.

On 23 June 2nd Battalion 27th Marines relieved 1/27 Marines on Go Noi. 2/27 Marines stayed on Go Noi until 16 July when it was relieved by 3/27 Marines. Marine losses during this period were 4 Marines killed and 177 wounded for 144 PAVN/Vietcong killed.

On 31 July, BLT 2/7 Marines which had just completed Operation Swift Play in the Da The mountains 6 km south of Go Noi arrived on the island and relieved 3/27 Marines.

Land clearing operations on Go Noi continued into August by which time much of the island had been completely leveled and seeded with herbicides. As enemy activity had been reduced to a minimal level it was decided to close the operation. While much of their infrastructure had been destroyed the PAVN/Vietcong continued to resist until the last as the Marines and Engineers withdrew across the Liberty Bridge harassed by sniper fire.

Operation Allen Brook concluded on 24 August, the Marines had suffered 172 dead and 1124 wounded and the PAVN/Vietcong 917 killed and 11 captured.

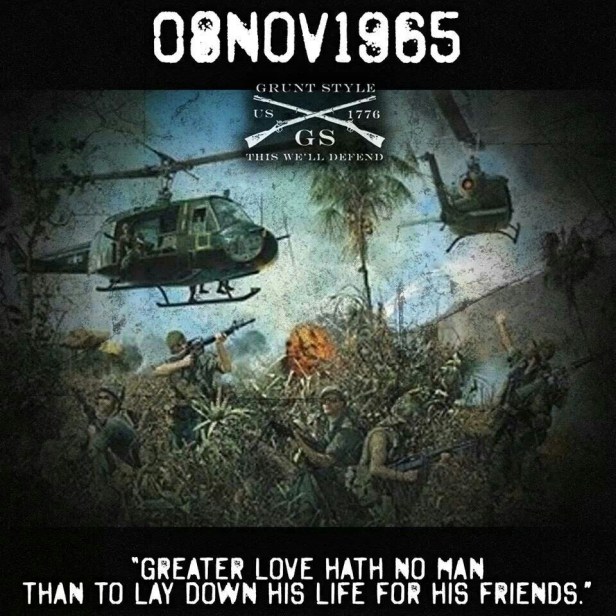

Operation Hump

This was a search and destroy operation initiated on 8 November 1965 by the 173rd Airborne Brigade, in an area about 17.5 miles (28.2 km) north of Bien Hoa. The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment deployed south of the Dong Nai River while the 1st Battalion, 503rd Infantry, conducted a helicopter assault on an LZ northwest of the Dong Nai and Song Be Rivers. The objective was to drive out Vietcong fighters who had taken position in several key hills. Little contact was made through 7 November, when B and C Companies settled into a night defensive position southeast of Hill 65, in triple-canopy jungle.

At about 06:00 on 8 November C Company began a move northwest toward Hill 65, while B Company moved northeast toward Hill 78. Shortly before 08:00, C Company was engaged by a sizeable enemy force well dug into the southern face of Hill 65, armed with machine guns and shotguns. At 08:45, B Company was directed to wheel in place and proceed toward Hill 65 with the intention of relieving C Company, often relying on fixed bayonets to repel daring close range attacks by small bands of masked Vietcong fighters.

B Company reached the foot of Hill 65 at about 09:30 and moved up the hill. It became obvious that there was a large enemy force in place on the hill, C Company was suffering heavy casualties, and by chance, B Company was forcing the enemy’s right flank.

Under pressure from B Company’s flanking attack the enemy force—most of Vietcong regiment—moved to the northwest, whereupon the B Company commander called in air and incendiary artillery fire on the retreating rebels. The shells scorched the foliage and caught many rebel fighters ablaze, exploding their ammunition and grenades they carried. B Company halted in place in an effort to locate and consolidate with C Company’s platoons and managed to establish a coherent defensive line running around the hilltop from southeast to northwest, but with little cover on the southern side.

Meanwhile, the Vietcong commander realized that his best chance was to close with the US forces so that the 173rd’s air and artillery fire could not be effectively employed. Vietcong troops attempted to out-flank the US position atop the hill from both the east and the southwest, moving his troops closer to the Americans. The result was shoulder-to-shoulder attacks up the hillside, hand-to-hand fighting, and isolation of parts of B and C Companies; the Americans held against two such attacks. Although the fighting continued after the second massed attack, it reduced in intensity as the Vietcong troops again attempted to disengage and withdraw, scattering into the jungle to throw off the trail of pursuing US snipers. By late afternoon it seemed that contact had been broken, allowing the two companies to prepare a night defensive position and collect their dead and wounded in the center of the position. Although a few of the most seriously wounded were extracted by USAF helicopters using Stokes litters, the triple-canopy jungle prevented the majority from being evacuated until the morning of 9 November.

The result of the battle was heavy losses on both sides—49 Paratroopers dead, many wounded, and 403 dead Vietcong troops as an estimate by the US troops.

Operation Hump is memorialized in a song by Big and Rich named 8th of November. The introduction, as read by Kris Kristofferson, is:

Battle of An Loc

The Battle of An Lộc was a major battle of the Vietnam War that lasted for 66 days and culminated in a decisive victory for South Vietnam. In many ways, the struggle for An Lộc in 1972 was an important battle of the war, as South Vietnamese forces halted the North Vietnamese advance towards Saigon.

On the evening of April 7, elements of the PAVN 9th Division overran Quần Lợi Base Camp. Its defenders, the 7th Regiment of the 5th Division, were ordered to destroy their heavy equipment (including a combined 105mm and 155mm artillery battery) and fall back to An Lộc. Once captured, the PAVN used Quần Lợi as a staging base for units coming in from Cambodia to join the siege of An Lộc. Key members of COSVN were based there to oversee the battle.

On April 8, the small town of Lộc Ninh was overrun and about half of the defenders escaped to An Lộc.

The ARVN defenders (8,000 strong) did have one card to play throughout the battle, the immense power of U.S. air support. The use of B-52 Stratofortress bombers (capable of carrying 108 MK82 (500 pound) bombs on one run) in a close support tactical role, as well as AC-119 Stinger and AC-130E Spectre gunships, fixed-wing cargo aircraft of varying sizes, AH-1 Cobra attack helicopters and Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) A-37s. These methods worked to blunt the PAVN offensive. At this stage in the war, the PAVN often attacked with PT-76 amphibious and T-54 medium tanks spearheading the advance, usually preceded by a massive artillery barrage. These tactics reflected Soviet doctrine, as the PAVN had been supplied with Soviet and Chinese Communist equipment, including jets, artillery, and surface to air missiles since the beginning of the war. The battle eventually stagnated and became a periodic trade of artillery barrages. This was most probably a result of casualties sustained in the frustrated attacks on heavily entrenched enemy positions in control of a withering array of supporting firepower.

The first attack on the city occurred on April 13 and was preceded by a powerful artillery barrage. The PAVN captured several hills to the north and penetrated the northern portion of the city held by the 8th Regiment and 3rd Ranger Group. ARVN soldiers were not accustomed to dealing with tanks, but early success with the M72 LAW, including efforts by teenaged members of the PSDF went a long way to helping the overall effort. The 5th Division commander, General Hung, later ordered tank-destroying teams be formed by each battalion, which included PSDF members who knew the local terrain and could help identify strategic locations to ambush tanks. They took advantage of the fact that the PAVN forces, who were not used to working with tanks, often let the tanks get separated from their infantry by driving through ARVN defensive positions. At that point, all alone inside ARVN lines, they were vulnerable to being singled out by tank-destroying teams.

April 15 saw the second attack on the city. The PAVN were concerned that because the ARVN 1st Airborne Brigade had air-assaulted into positions west of the city, that they were now coming to reinforce the defenders. Again the PAVN preceded their attack with an artillery barrage followed by a tank-infantry attack. Like before, their tanks became separated from their infantry and fell prey to ARVN anti-tank weapons. PAVN infantry followed behind the tank deployment, assaulted the ARVN defensive positions, and pushed farther into the city. B-52 strikes helped break up some PAVN units assembling for the attack. This engagement lasted until tapering off on the afternoon of April 16.

Unable to take the city, the PAVN kept it under constant artillery fire. They also moved in more anti-aircraft guns to prevent aerial resupply. Heavy anti-aircraft fire kept VNAF helicopters from getting into the city after April 12. In response, fixed wing VNAF aircraft (C-123’s and C-119’s) made attempts, but after suffering loses, the U.S. Air Force took over on April 19. The US used C-130’s to parachute in supplies, but many missed the defenders and several aircraft were shot down or damaged. Low altitude drops during day and night did not do the job, so by May 2, the USAF began using High Altitude Low Opening (HALO) techniques. With far greater success, this method of resupply was utilized until June 25, when the siege was lifted and aircraft could land at An Lộc. Over the entire course of the resupply effort, the garrison recovered several thousand tons of supplies—the only supplies it received during the siege.

On May 11, 1972, the PAVN launched a massive all-out infantry and armor (T-54 medium tanks) assault on An Lộc. The attack was carried out by units of the 5th and 9th PAVN divisions. This attack was repulsed by a combination of U.S. airpower and the determined stand of ARVN soldiers on the ground. Almost every B-52 in Southeast Asia was called in to strike the massing enemy tanks and infantry. The commander of the defending forces had placed a grid around the town creating many “boxes”, each measuring 1 km by 3 km in size, which were given a number and could be called by ground forces at any time. The B-52 cells (groups of 3 aircraft) were guided onto these boxes by ground-based radar. During May 11 and 12, the U.S. Air Force managed an “Arc Light” mission every 55 minutes for 30 hours straight—using 170 B-52’s and smashing whole regiments of PAVN in the process. Despite this air support, the PAVN made gains, and were within a few hundred meters of the ARVN 5th Division command post. ARVN counter-attacks were able to stabilize the situation. By the night of May 11, the PAVN consolidated their gains. On May 12, they launched new attacks in an effort to take the city, but again failed. The PAVN launched one more attack on May 19 in honor of Ho Chi Minh’s birthday. The defenders were not surprised, and the attack was broken up by U.S. air support and an ambush by the ARVN paratroopers.

After the attacks of May 11 and 12, the PAVN directed its main efforts to cut off any more relief columns. However, by the 9th of June this proved ineffective, and the defenders were able to receive the injection of manpower and supplies needed to sweep the surrounding area of PAVN. By June 18, 1972, the battle had been declared over.

The victory, however, was not complete, QL-13 still was not open. The ARVN 18th Division was moved in to replace the exhausted 5th Division. The 18th Division would spread out from An Lộc and push the PAVN back, increasing stability in the area.

On August 8, the 18th Division launched an assault to retake Quần Lợi, but was stopped by the PAVN in the base’s reinforced concrete bunkers. A second attack was launched on August 9 with limited gains. Attacks on the base continued for 2 weeks; eventually one-third of the base was captured. Finally, the ARVN attacked the PAVN-occupied bunkers with TOW missiles and M-202 rockets, breaking the PAVN defense and forcing the remaining defenders to flee the base.

The fighting at An Lộc demonstrated the continued ARVN dependence on U.S. air power and U.S. advisors. For the PAVN, it demonstrated their logistical constraints; following each attack, resupply times caused lengthy delays in their ability to properly defend their position.

Operation Lam Son 719

Despite equivocal results in Cambodia, less than a year later the Americans pressed the South Vietnamese to launch a second cross-border operation, this time into Laos. Although the United States would provide air, artillery, and logistical support, Army advisers would not accompany South Vietnamese forces. The Americans’ enthusiasm for the operation exceeded that of their allies. Anticipating high casualties, South Vietnam’s leaders were reluctant to involve their army once more in extended operations outside their country.

The Ho Chi Minh Trail was an ever-changing network of paths and roads. For North Vietnam, keeping the Ho Chi Minh Trail open was a top priority. American intelligence had detected a North Vietnamese buildup in the vicinity of Tchepone, Laos, a logistical center on the Ho Chi Minh Trail approximately twenty-five miles west of the South Vietnamese border. The Military Assistance Command regarded the buildup as a prelude to a North Vietnamese spring offensive in the northern provinces. Like the Cambodian incursion, the Laotian invasion was justified as benefiting Vietnamization, but with the added bonuses of spoiling a prospective offensive and cutting off the Ho Chi Minh Trail. This would be the last chance for the South Vietnamese to cut the Ho Chi Minh Trail while American forces were available to provide support.

Phase I, designated DEWEY CANYON II, began at 0001 local time on 30 January, as US troops maneuvered to secure western Quang Tri province. An assault airstrip became operational at Khe Sanh by 3 February; Route 9 was repaired and cleared to the Laotian border by 5 February. Behind this cover, the better part of two South Vietnamese divisions massed at Khe Sanh in preparation for the cross border attack.

Because of security leaks, the North Vietnamese were not deceived. Within a week South Vietnamese forces numbering about 17,000 became bogged down by heavy enemy resistance, bad weather, and poor attack management. The ARVN had run into a superior North Vietnamese force fighting on a battlefield that the enemy had carefully prepared. In midsummer 1970, the People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN) General Staff began drawing up combat plans, deploying forces, and directing preparation of the battlefield. By 8 February 1971, when the ARVN crossed the Laotian border, the North Vietnamese, by their own account, had massed some 60,000 troops in the Route 9-Southern Laos front. They included five main force divisions, two separate regiments, eight artillery regiments, three engineer regiments, three tank battalions, six anti-aircraft regiments, and eight sapper battalions, plus logistic and transportation units-according to North Vietnamese historians “our army’s greatest concentration of combined-arms forces . . . up to that point.”

Aided by heavy U.S. air strikes, including B-52s, and plenty of artillery and helicopter gunship support, the South Vietnamese inched forward and after a bloody, month-long delay, air-assaulted on March 6 into the heavily bombed town of Tchepone. This was the last bit of good news from the front. This was the RVNAF’s last chance to make a dramatic impression upon the North Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese by now had massed five divisions with perhaps 45,000 troops-more than twice the ARVN force in Laos-for counterattacks. The North Vietnamese counterattacked with Soviet- built tanks, heavy artillery, and infantry. They struck the rear of the South Vietnamese forces strung out on Highway 9, blocking their main avenue of withdrawal. Enemy forces also overwhelmed several South Vietnamese firebases, depriving South Vietnamese units of desperately needed flank protection. The South Vietnamese also lacked enough antitank weapons to counter the North Vietnamese armor that appeared on the Laotian jungle trails and were inexperienced in the use of those they had. U.S. Army helicopter pilots flying gunship and resupply missions and trying to rescue South Vietnamese soldiers from their besieged hilltop firebases encountered intense antiaircraft fire.

On March 16, ten days after Tchepone was taken, President Thieu issued the order to pull out, turning aside General Abrams’ plea for an expansion of the offensive to do serious damage to the trail.

The ARVN withdrawal, conducted mainly along Route 9, ran from 17 until 24 March. A North Vietnamese ambush on 19 March littered the road with wrecked vehicles. Artillery pieces were abandoned, and a good many men had to make their way on foot to landing zones for evacuation. American media carried pictures of ARVN soldiers clinging to the skids of US helicopters.

The South Vietnamese lost nearly 1,600 men. The U.S. Army’s lost 215 men killed, 1,149 wounded, and 38 missing. The Army also lost 108 helicopters, the highest number in any one operation of the war. Supporters of helicopter warfare pointed to heavy enemy casualties and argued that equipment losses were reasonable, given the large number of helicopters and helicopter sorties (more than 160,000) that supported LAM SON 719. The battle nevertheless raised disturbing questions among Army officials about the vulnerability of helicopters in mid- or high-intensity conflict to any significant antiaircraft capability.

Watch a short 5-minute video from an American pilot who participated in the operation. Afterward, click on the back arrow key to return to this article:

NOTE: There are volumes of books that list every battle / operation of the war. This was not my intent here.

Information used for the series of battles in this article was obtained from The History Channel, Military Channel, YouTube, Tropic Lightning News, Wikipedia, and Vietnam Magazine.

Click below for more articles in this series:

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

Hi, JP,

I read part one of your article and have the rest saved on my reading list. My friend died in 1968, and it must have been during one of these battles. I couldn’t see one of the video posted, but I could see the one posted with Operation Hump.

When I see the count of all the men that were lost, I could cry. I do know that my friend’s father was totally broken when he lost his only son. He never recovered from that loss and his will to live just went away.

Thank you so much for taking the time to do this.

Think about writing the battles as a book. I know it would be a lot of work, but think about it.

Take care, Partner. I’m glad you made it back.

Shalom shalom

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Pat!

LikeLiked by 1 person

1st. Cavalry Division ( M.G. Roberts Commander ) Baiting Operation – started March 26 , 1970 , C Co. 2nd / 8th Recon found the enemy , March 29 , 1970 F.S.B. Jay Battle , and then April 1 , 1970 Of F.S.B. Illingworth Battle – really BAD Baiting Operation – 42 Americans Died and 137 Wounded Soldiers / Purple Hearts . Memorial at Fort Sill , Oklahoma – 50 years later – NO Unit Battle Unit Award ribbons !

LikeLike

Thank you Karen! So sorry for your loss!

LikeLike

I’m a widow of a Marine of the Vietnam war…he served with India 3/1 and Mike 3/1 in 1969……wounded twice…once with India and once with Mike……I enjoyed reading your articles…although it made me feel a little sick…thinking about what so many went through and endured….and what my husband went through and saw……he had PTSD very bad….nightmares and night sweats…but he was a good man and we were married 30 years before he died May 21, 2002….he will always be my Hero….”Semper Fidelis”…………

LikeLike

Very good

LikeLike

Very good wish I could talk to you 860 774 4736

LikeLike