By this article, it appears that Australia treated their returning Vietnam Veterans far harsher than those returning to the United States. It’s taken decades, but one former Digger took on the government to make things right. Here’s his story:

The author, serving with 10 Platoon, D Company, the 4th Battalion, 1969

The same sentiment surely applied to the soldiers from Australia who also went to fight the war — the flowers of the nation’s youth. Surely, its finest young men.

And indeed, that was the case. Because the fact was, only the very best of men could get to the killing fields of Vietnam. Make no mistake about that. The Jungle Training Centre at Canungra made sure of it. And I’m not just talking about the fighting man of our Army — the infantryman — because even the cooks and cleaners and bottle-washers had to prove themselves at that testing ground, before they left Australia.

To put it simply, weak men, or cowardly men, or men deficient in some other area, never made it to Vietnam, or at least not onto its shores. The processes of elimination weeded them out beforehand.

So yes, the finest of men fought in that war. Over 58,000 of them were Australians, according to the Vietnam Veterans’ Nominal Roll. Indeed, the “flower of our youth.”

A typical Australian infantry platoon — the recon Platoon of the 5th Battalion led by Lt Michael von Berg MC (far left of the back row) in 1966. Photo courtesy of Daryl Henry, a Canadian War Correspondent

They are locked away in jails, in clinics, and in mental asylums, and in each case represent a greater percentage of the otherwise ‘normal’ members of society. Many live out their lives in isolated makeshift camps in remote country areas across all states of Australia, armed and dangerous in many instances. There is anecdotal evidence that some live on boats in the Whitsundays, coming to shore only for re-supply purposes, and in secure camps in other, isolated regions. Others never set foot outside of their homes. Only about 12% are married to their first wives, and for many of them it’s only because of the good graces of the particular woman — a special breed.

Most of the men are holding onto a seething anger, without really understanding why — an anger slowly eating away what is left of their health, and souls.

So, how is this so? How is it possible that the ‘flower of our youth’ has become such a tormented group, in just over three decades?

As a returned veteran of that war myself, a regular soldier who joined the Army willingly and asked specifically to serve as infantryman, and who was subsequently wounded in action, I have particular views on the reasons why this has happened.

The author, as forward scout with C Company 9th Battalion in July 1969

Not only did he have to face new, improved weapons of waging war, the Vietnam veteran also fought in an environment where he had to endure nature’s worst — the fire-ants, snakes, scorpions and leeches, even tigers and monkeys and wild pigs on occasion, and at the other end of the scale, minuscule parasites that entered the body through the tightest of openings. He fought in sauna-like heat and humidity in the dry season, and put up with the torrential monsoon storms of tropical Asia during the wet.

Then there were the sights and sounds of war itself, the death of mates, the torn-apart bodies, the makeshift graves, and all the variables of such combat. For one man it was to stand on a mine and have your legs blown off; for another, it was to fill a canteen with water from a creek as a dead body floated past; for another it was to kill off a wounded enemy soldier as he defiantly tried to throw yet another grenade even as he died; for another it was to sit at a the machine-gun of a chopper as it loaded men aboard, knowing they were sitting ducks; for another it was just the never relenting realisation that the enemy could strike him at any time at any place and that there was no refuge; for another, it was the fear of his ship being sunk; for another, it was to go down into underground tunnels, or having to defuse mines; for another, it was to handle body bags and severely wounded men; for another, it was to know he had drunk a chemical cocktail that will likely up and strike him in days to come; and for yet another it was to have his body torn open by high-impact bullets. And so on.

The result of a machine-gun bullet on Private Don Tate on July 1969- a bullet that shattered his hip bones, requiring hospitalisation for more than two years, and leaving him permanently disabled

Viet Cong bodies following the successful night ambush at Thua Tich by the 2nd D&E Platoon on May 29th 1969

Some of what the veteran experienced, he had been trained for, but the truth about soldiering is that the reality of war is a far greater burden than the expectation of it. The worst aspects of soldiering, and the true horror of warfare itself, was fully revealed as he watched his fellow soldier and enemy die alongside him in the most savage type of bloody combat. Then, if he was lucky and survived the contacts and ambushes and battles, but was physically wounded, he suffered the ignominy of being packed like a sardine into the dirty holds of lumbering old cargo planes for the three-day trip home to hospitals in Australia, and thinking his war was over.

But it wasn’t.

I ended up taking that same route home myself, and well remember that trip home with about forty other wounded men. There we were, piled two and three high in those dirty old planes with bottles of blood and urine dangling everywhere, and with wax stuffed in our ears to drown out the sound of the engines — a hell of its own.

For wounded men, this was the final indignity. Not only would the wounds of many of us get more infected during the flight, we came to realise very quickly that now we were second-class soldiers, and would be second-class citizens when we got home.

We had given the war machine our bodies. Now we were superfluous to both the Army, and the country.

The veteran was not aware of it at the time, but soon learned, that the wounded and dying were essentially smuggled back into the Military Hospitals, away from prying media eyes, and aware that newspapers only printed a doctored list of casualties each day, generally only listing casualties from their own states on many occasions, or staggering the casualty lists over a number of days to allay concern about the number of men falling. Couldn’t have the public getting too outraged, you see.

But what he didn’t know then, but would learn very quickly, was that if he joined the list of wounded men, or the queue of men whose health would deteriorate so quickly later on, he could not only look forward to a life of relative poverty, but a life of battles with those insensitive, recalcitrant bureaucracy supposedly meant to support him — The Department of Veterans’ Affairs and the Australian War Memorial could not know that they would falsify reports, hide information, and battle him every inch of the way for meagre pensions to compensate him for his sacrifices, or assist him to validate aspects of his war service.

In my case, because of maladministration and a cover-up of atrocities that concerned a second unit I’d fought in — the 2nd D&E Platoon, my service history was bastardised. It took me 29 years to prove to the Army that I’d served in the 9th BattalIon despite a plethora of documentation proving that I had. The Army eventually corrected its error, updated the Nominal Roll, and sent me a letter of apology from a current, serving General (Fergus McLachlan).

But the damage was done. There are some who have a lot to answer for.

My personal situation aside, the fact is that the young man, now a war veteran, and no longer the same young man who had left his country’s shores a year earlier, came home.

If not a casualty like myself, he either flew home in half a day by jet, or took a week or so by supply ship. Straight from the battlefield to normal life again, although by now his sense of normalcy had new parameters.

Now, he found he had new battles to fight.

Already traumatised by experiences which had been terrifying, dehumanising, and soul-shattering, he was met at airports and sea ports with open hostility and disgust from the society he had risked his life for. There were no welcome home, mates. No well dones. No victory parades. No sir. Or not for a quarter of a century, at least.

Instead, he confronted other armies.

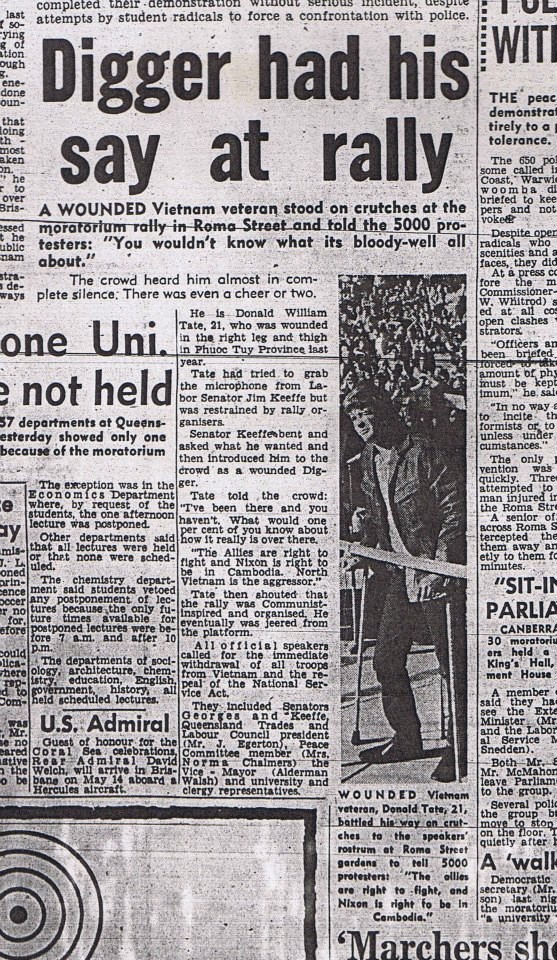

First, there was the Moratorium marches — peace protestors made up of friends, family and workmates unable to differentiate between the war they were objecting to, and the warrior who had fought it. They mocked and jeered him. Threw red paint at him in one instance, or pig’s blood. Called him “baby-burner”. Spat at, and abused him in ways no other returning soldier from this country had ever endured.

Many veterans didn’t stand up to the Moratorium marchers. I did.

When Prime Minister Billy Hughes sent men of to World War 1, he told the Australian public ‘…we say to them, You go and fight, and when you come back we will look after your welfare…’ and he was a man of his word, initiating the first repatriation benefits for returned veterans. But successive Prime Ministers and their fat-arsed Ministers and bureaucrats of that portfolio have been lesser men and women, and in no way have they honoured Hughes’ pledge to the Australian public.

Then, he faced the greater army — society at large, armed with the weapons of public indifference and disregard for what the digger may have gone through. Instead of acclaim for a job well done, he was told that he hadn’t really fought in a war at all, it had been a ten-year police action, and that he wasn’t as good a soldier as his father or father’s father had been anyway. He was ridiculed in that bastion of the returned veteran — the Returned Serviceman’s League — for losing a war, a first in the nation’s history.

He could argue that he had well and truly subdued the enemy in the particular region allocated to Australia in the war, but it would do him no good. The veterans of the earlier wars, even those who hadn’t actually fired a shot in anger took great delight in putting down the Vietnam veteran as an inferior man. Subsequently, any pride he may have felt for what he had done, at putting his life on the line for his country, was stripped away from him.

Came home too, to find the available jobs taken by men who hadn’t fought in the war. Men who got their degrees and diplomas while he trod the bloodied paddy fields and jungle tracks of Vietnam, then who would lord it over him, and dictate his life in a plethora of bureaucracies for evermore. Tough luck, mate. It was every man for himself.

The veteran never really came to terms with the reaction he received back at home, never understood or comprehended the intensity of the response from his fellow Australians. But over the years, he was able to rationalise a little of it, mulled it over while the bitterness festered.

He was already aware, of course, of the political history surrounding Australia’s involvement in the war.

The thinking veteran suspected that Prime Minister Menzies’ excuse for committing us to war was probably based on falsehood, and that the S.E.A.T.O and A.N.Z.U.S treaties were international jokes, but young men can be excused their naiveté. Years later he learned that Menzies deliberately lied to the Australian public in relation to our involvement in the War, but the damage was done by then anyway, and it mattered not. There has never been a war fought without political hypocrisy of some sort.

He watched the politicians send their own sons out of the country on extended European jaunts while the sons of lesser men were selected to fight and die. He suspected that the birth dates of prominent leaders of both government and industry somehow would never be plucked from the national service ballot — that lottery of death. And some even knew that Menzies himself, as a twenty-year-old, had opted not to enlist when Australia needed volunteers for the World War 1 killing fields.

Nothing unusual about any of that, of course. That’s the way of politicians of all persuasions.

He had seen the same politicians fly into Vietnam by the first-class jet on ‘fact-finding’ missions. Knew men like Jim Cairns were having trade talks with the enemy, even as Australians bled on that foreign soil. Heard stories of how Andrew Peacock landed by helicopter three times so photographers could get the best angles and profiles like McArthur had done many years before in the Philippines. And knew that Malcolm Fraser was not telling all he knew about the Agent Orange scourge that would reap such a horrific whirlwind decades later.

And then, as the years flew by, he watched a succession of indifferent, cowardly politicians crush the veteran’s spirit through the insensitive administration of the Department of Veterans Affairs. Rarely does that portfolio enjoy a Minister of substance and maturity- look at the lot we’ve had to endure……Billson, Griffin, Snowden, Ronaldson, Payne, Chester, and co. We hold our collective breaths waiting for a real man to fill that position.

Most Veteran Affairs Ministers are more concerned with junkets and jaunts to foreign battlefields instead of tackling the substantial decline in veteran pensions caused by the slash and burn approach governments have had with respect to veterans’ compensation for war wounds, and superannuation. Veterans seethe at this, knowing that politicians’ superannuation has increased by 120% in the last twenty years, while that of veterans has gone up less than half of that.

Finally, the veteran learned that he was probably poisoned in the most insidious of ways while he fought in Vietnam.

In truth, he had fought in a War in which something like 40 billion litres of assorted poisons, insecticides and pesticides were sprayed over the land in the defoliation processes code-named Operation Ranch Hand (or Operation Hadesas it was more correctly called earlier). He breathed in the poisons, showered with waters infected by them, drank them, and even helped spray them himself (never being told of what dangers he was exposing himself to). Even sailors couldn’t escape the scourge of Agent Orange, because they not only loaded and unloaded the poisons, they too, drank water brought to them from Vung Tau — waters already polluted by the poisons.

He was not to know that they would prove to be lethal, and that he could expect to manifest all kinds of debilitating illnesses before they killed him years down the track, or if not that, they could drive him insane. Or leave a legacy of horror to live on in his children and grandchildren for generations to come.

But he knows some of that today, thanks to gutsy crusaders like Jean Williams (Cry in the Wilderness) and Dr. John Pollack, among many others. Knows that certain chemical warfare files he was part of have been classified as “Never to be Released to the Australian Public” — courtesy of Prime Minister Bob Hawke, or at least not until 2020, by which time the veteran will most likely be dead. These include the so-called Malarial Files — the official record of the testing processes carried out using the veteran as an unwitting guinea-pig.

Friedreich Nietzsche, in The Antichrist said that evil was whatever springs from weakness, and in this respect, the weakness of subsequent Australian governments to fully reveal the truth about what chemical companies were allowed to do this country’s fighting men is evil personified, and the actions of weak and cowardly men.

So yes, the Vietnam veteran has much to be angry about. It’s why the platitudes he hears like ‘Put it behind you!’ cuts him so deep. They are logs on his shoulders difficult to dislodge, but the thing is, repressed anger or sadness can’t be repressed forever.

At some point, the demons are released. It’s why so many men have chosen that final alternative and taken their own lives, or live lives festering with an assortment of illnesses. It’s why so many die so young.

So there he sits, the Vietnam veteran, all these years on.

Psychologically unbalanced by the actual horror of war and his exposure to a bizarre array of toxic chemicals while fighting it, alienated and ostracised by family and friends because the war changed him so remarkably, disregarded by the very society he had gone off to defend, physically broken by the use of various experimental drugs he was forced to take, and wounded by bullet, steel fragment or booby trap, he watches the world go by without him, and his resentment and anger become manifestly more obvious.

‘O war! Thou son of hell!’ wrote Shakespeare. How apt those words for the man who went off to fight in Vietnam.

This article originally appeared on Medium.com on 10/31/2018.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I‘ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

Outstanding to say the least. I served with Victor Coy under command of 2RAR May 70/71

LikeLike

It is upsetting how our Aussie brothers were treated upon arriving back home. I thought that we were treated badly! They were hard charging troops who fought with honor for the most part except for a situation or two.

LikeLike

So so sad and despicable that these heros were abandoned . Thank you to you all….I’ll be forever grateful.

LikeLike

Excellent article. Like we in the US, you guys are fighting the same war, it never seems to stop. The BS from the VA, and trying to get care still continues. I was proud to have worked with some Aussies from Vung tau. I hope they all made it back home.

LikeLike

It is so strange to me that the only soldiers welcomed home were those fighting for societies in which contrary opinions are stomped on.

LikeLike

Good and Accurate article.

The treatment was much the same in Minnesota in the USA. I was deprived of my medical care by the V A. They blinded me in one eye by turning me away, and I was treated like shit.

I was harassed out of my first engineering job as a “baby killer”.

I took it off my resume that I was a veteran and then I LIED about why my leg was screwed up and why I was blind in one eye.

I’m glad I’m old and don’t have long to go!

LikeLike

Surprising and not publicly known off the treatment they received as Vietnam Veterans.

LikeLike

Thankyou, John, for putting all that together.

The link was sent to me by my father in law – an RAN clearance diver of 9 tours, who is one tough cookie, but still has demons he’s been able to keep in check. One of the ‘lucky’ ones.

Like many have said – a hard read, but something all Australians need to know. It was a bad background colour to my youth, even with my parents shielding us from the worst of it, but the gaps have slowly been filling in.

A very dear friend was directly affected by the trauma passed on by his returning Veteran father, who’s story he slowly pieced together after decades of silence.

Thanks again, and will be sharing the link with my family and friends.

LikeLike

What Ive just read is “nothing but the truth so help me god”. 5PL B coy 2rar 1967-1968

LikeLike

Further to my comments, My future Son in Law on his first and only visit to us in 1998 opened up the conversation with my Wife and I to say “you are a Baby Killer and your Wife is a Whore for marrying you!” so as result of that we have not seen my Daughter or my Son In law since then.

We where not invited to the Wedding and do not know if we are Grandparents. This child was not born during my time in SVN and has no idea of what it caused to us in the Australian Armed Defence Force and still affects us.

LikeLike

Well spoken ,a very good article,

LikeLike

I recently went on a trip to New Zealand. It is my understanding that many Kiwi’s served in Vietnam in the Australian Army. In Auckland, NZ, there is a very large War Memorial Museum. It is organized very nicely by the timeline of battles fought. I walked along and saw all the wars and battles that the Australian Army had fought in from the Boer War to Korea, there were displays and photos of actions. I was interested in the Vietnam era because I had served near an Aussie unit. When I reached the timeline where Vietnam should have been, it suddenly jumped to serving under the blue beret, being part of a United Nations force. There was no photos or even a mention about Vietnam in their timeline. The only time Vietnam is listed is on a memorial wall to all from New Zealand military that died in wartime. On my way out of the museum I was stopped by a man who wanted me to take a survey regarding the museum. I told him I only had one remark. Why was there no reference to Vietnam in their timeline? Not even one photo, only the list of names on a wall. Was your country, is your country ashamed of those who served in Vietnam? He simply looked at me with no response. This article explains what was and is occurring to our brothers in that part of the world.

LikeLike

Good on you, Don. Keep it up, mate! Don’t let them forget!

LikeLike

Hard to read. Would have hoped that our Ausie brothers would have been treated differently than we were, but it appears that they had it even worse. Those of us that are left all old men and women now but let us pledge to never turn our backs on our younger veteran brothers and sisters – to never treat them the way we were treated.

Welcome home everyone. We did a damn good job and for that we do not have to bow to anyone.

LikeLike

A true gut wrenching story that affects all our Vietnam returned service men and women I have spent over 30 years suffering the affects ofAgent Orange the last 13years I have spent most of my time useless in bed reading a library or seeing doctors and having operation so now we have anew healthy minister his name is health minister Hunt and he will be as useless as all the other health ministers

LikeLike

Nothing J Chester mp is the minister for veterans affairs from2019 and he will do nothing either they are all hand sitters. Only one who tried was Christopher Payne but they put him in the position he was better resigning

LikeLike

I think this is very accurate

The forgotten veterans

Who really cares!!!!

I was diagnosed with ptsd by a physician in 2007 and am still trying to get a full pension.

You would have no idea the shit I am going through.

Was their any thought when our youth was taken away from us and were told to fight in a country that most of us had never heard of.

Who really cares!!!!!

LikeLike

I think this is very accurate

The forgotten veterans

Who really cares!!!!

I was diagnosed with ptsd by a physician in 2007 and am still trying to get a full pension.

You would have no idea the shit I am going through.

Was their any thought when our youth was taken away from us and were told to fight in a country that most of us had never heard of.

Who really cares!!!!!

LikeLike

Thank you for the article.

LikeLike

Made me reflect on my life. I am now 73 and served with the R.A.N.H.F.V.

LikeLike

The brutal truth.

LikeLike

Having known a few of Australia’s finest, I admit total surprise, disappointment, and sadness. I had always thought that we, the American soldiers, were the only ones treated with disdain and disrespect. I will just say to every Aussie bvb and ass still kicking, tell those mindless morons to push off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Being a Vietnam era veteran of the USMC I had no idea that our Aussie veterans suffered and continue to suffer so much. While stationed in Okinawa in 1963-64 we (advisors) trained Aussies to fight in ‘Nam. All that changed in ’65 when we joined them as combatants . Someone needs to right this wrong as our veterans down under suffer from benign neglect.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The author “hit the nail on the head “! This article states the facts clearly and succinctly. I wish every individual were forced to read it. WELL DONE BROTHER!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am an Aussie Vietnam Vet so can recognise myself and a lot of mates in this story. What wasnt said was that the Labor politicians (our version of US ‘liberals’) were encouraging unions to strike against us, and supporting students who were collecting money to buy ammunition and medical supplies for the VC.

No mail deliveries, no supplies, no beer (we had to beg beer and ammunition off the US stores), and school teachers at home harrassing our kids. We even had our own Jane Fonda in the guise of communist sympathesisers in the press who wrote how wonderful the North was and how bad we were.

The greatest indignity is that our unit received commendations from US commanders (we were under operational control of US unit) but were knocked back by the US Government because we were Australian, and by the Australian Government because we were assigned to a US unit.

Hopefully the same never happens to our younger veterans.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for supporting this article, Phil. God Bless.

LikeLike

Don was correct about the Australian Army battalions doing Canungra but for myself I was in the Royal Australian Air Force and I had just returned from Ubon Ratchathani in Thailand after six months there (250 of us with five thousand USAF across the airfield) nine months later I was posted for 12 months to Vung Tau/Phan Rang my jungle training consisted of one day at a Rifle Range out the back of RAAF Base Pearce Western Australia fired an assortment of weapons and was told OK you can go to SVN now! 67-68 Ubon, 69-70 SVN fifteen months later RAAF Base Butterworth malaysia 71-72. typical RAAF send me to SVN after one days firing of weapons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very interesting stories that I think should be some way teaching the older children in school what these heroes had to do like it not they were sent there to do a job & they had survive

LikeLiked by 1 person

Danang, 1965-1966: Via the “Dog Patch” Gate @ the airfield turn right and a few clicks down the road was the Aussie Compound. They were professional Soldiers, all seasoned NCOs. Advisers to the Vietnamese forces. Some Taiwan Merc’s & Korean Rangers were in that area too. This article is surprising. Those Aussie NCOs were totally professionals & Gung Ho in their job. High Moral reined. Semper Fi! from a retired Marine, 1958-1986.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article,I was chief Ammo Inspector,at Qui Nhon Ammo Base depot,from Dec 67 to Jan 69,I never knew,that the Australian VN brothers,were treated as bad as us . crying damn shame,I am 100% disabled,due to agent Orange,I’v had both vocal cords removed,and now have a hole in my throat to talk thru,with the help of an electronic hand held machine,And,I talk like a robot,Welcome home my Aussie brotyhers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

WOW

Been there, 68-69, Aussie docs stitched up my head, best article ever.

The Aussie’s were the best brothers there with us. 👍🙏🏻

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. the ones who were not there will never understand. RVN 68_69

LikeLiked by 1 person

SAD But an excellent article

God Bless & keep all of you

Was’nt aware that you all

Had to suffer like our men!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Wwll done, fight not iver just because you are home

LikeLiked by 1 person

Having known a few of Australia’s finest, I admit total surprise, disappointment, and sadness. I had always thought that we, the American soldiers, were the only ones treated with disdain and disrespect. I will just say to every Aussie bvb and ass still kicking, tell those mindless morons to push off.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Pddogbiker, Thank you for all the stories that you are sharing with us Vietnam vets. I was in country from Nov 68 to nov 69, I served with 9th avn bn of the 9th ID from Dec 1 to July 69 on Dong Tam, 4th corps in the Deta, 9th ID was deactivated and sent to Hawaii. I was transferred to 3/5 Air Cav on Dong Tam, we stayed for one month to guard the Helipad, we didn’t fly anymore missions out of Dong Tam. Then on Aug 1st 3/5 Air cav was sent to Vinh Long, and attached to 7/1 Air cav under the first aviation Brigade.I was a crew chief on a Huey Cobra for my last 3 months with the 9th avn bn .I was looking up info on Huey Tail rotor chain and the maintenance on them, and came across a guy from Australasia on the net who interviewed me about the Huey tail rotor chain. He said he is writing a book all about the Huey tail rotor chain. He posted my interview on the internet, and he titled it, Bill Vaughan author at The Huey Bracelets project. It is on the internet with me and pictures of my Cobra.Â

Bill Vaughan, Author at The Huey Bracelets Project – Jan 12, 2015 - Bill Vaughan in front of bird with Huey bracelet … âAll UH1 and AH1 Hueys during the Vietnam error used a Tail Rotor chain to change the pitch …hueybracelets.com ⺠2015/01/12 ⺠100-hour-maintenance

100 Hour Maintenance – The Huey Bracelets Project – Jan 12, 2015 - Bracelet made from tail rotor chain of Huey helicopter in Vietnam, with clasp installed by. My bracelet with new clasp. Bill Vaughan MechanicMissing: author â| Must include: author Images for bill Vaughan author of the Huey tail rotor bracelet project View allMore images for bill Vaughan author of the Huey tail rotor bracelet projectReport images

| | | | bill Vaughan author of the Huey tail rotor bracelet project – Google Search

|

|

|

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is an excellent post, John. I wasn’t aware that Aussie Vietnam vets were treated like this. Thanks for sharing Donald Tate’s story.

Looking forward to our talk on Spotlight Honors Feb. 20.

Bests,

Ron Yates

On Sun, Feb 2, 2020 at 1:40 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

> pdoggbiker posted: ” Donald William Tate, my long-time friend from > Australia, fellow author, and Vietnam Veteran, offers a personal look at > how Vietnam Veterans were treated in Australia since the war ended. It’s > not pretty! The author, serving wit” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for this article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a great piece of writing and it is all so very true.vietnam vet 68/69,1fd. sqn. rae. fsb,coral,ect.

LikeLike

Wow. Very interesting article. I was not aware of the plight of our Aussie Nam vet brothers. Thanks for publishing this John.

LikeLiked by 1 person