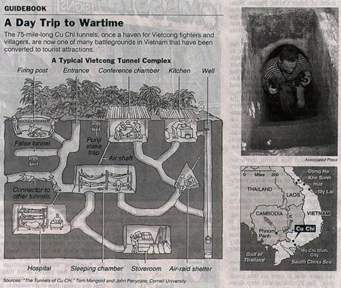

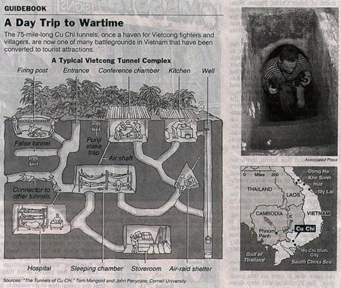

The tunnels of Củ Chi are an immense network of connecting underground tunnels located in the Củ Chi District of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam, and are part of a much larger network of tunnels that underlie much of the country. The Củ Chi tunnels were the location of several military campaigns during the Vietnam War and were the Viet Cong’s base of operations for the Tết Offensive in 1968.

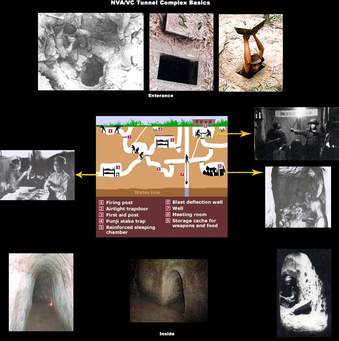

The tunnels were used by Viet Cong soldiers as hiding spots during combat, as well as serving as communication and supply routes, hospitals, food and weapon caches and living quarters for numerous North Vietnamese fighters. The tunnel systems were of great importance to the Viet Cong in their resistance to American forces and helped to counter the growing American military effort.

LIFE IN THE TUNNELS

American soldiers used the term “Black Echo” to describe the conditions within the tunnels. For the Viet Cong, life in the tunnels was difficult. Air, food, and water were scarce and the tunnels were infested with ants, venomous centipedes, scorpions, spiders, and vermin. Most of the time, soldiers would spend the day in the tunnels working or resting and come out only at night to scavenge for supplies, tend their crops, or engage the enemy in battle. Sometimes, during periods of heavy bombing or American troop movement, they would be forced to remain underground for many days at a time. Sickness was rampant among the people living in the tunnels, especially malaria, which was the second largest cause of death next to battle wounds. A captured Viet Cong report suggests that at any given time half of a PLAF unit had malaria and that “one-hundred percent had intestinal parasites of significance”.

The tunnels of Củ Chi did not go unnoticed by U.S. officials. They recognized the advantages that trapdoor held with the tunnels and accordingly launched several major campaigns to search out and destroy the tunnel system. Among the most important of these were Operation Crimp and Operation Cedar Falls.

Operation Crimp began on January 7, 1966, with Boeing B-52 Stratofortress bombers dropping 30-ton loads of high explosive onto the region of Củ Chi, effectively turning the once lush jungle into a pockmarked moonscape. Eight thousand troops from the U.S. 1st Infantry Division, 173rd Airborne Brigade Combat Team, and the 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment combed the region looking for any clues of PLAF activity.

The operation did not bring about the desired success; for instance, on occasions when troops found a tunnel, they would often underestimate its size. Rarely would anyone be sent in to search the tunnels, as it was so hazardous. The tunnels were often rigged with explosive booby traps or punji stick pits. The two main responses in dealing with a tunnel opening were to flush the entrance with gas, water or hot tar to force the Viet Cong soldiers into the open, or to toss a few grenades down the hole and “crimp” off the opening. This approach proved ineffective due to the design of the tunnels and the strategic use of trap doors and air filtration systems.

However, an Australian specialist engineering troop, 3 Field Troop, under the command of Captain Sandy MacGregor did venture into the tunnels which they searched exhaustively for four days, finding ammunition, radio equipment, medical supplies, and food as well as signs of considerable Viet Cong presence. One of their number, Corporal Bob Bowtell, died when he became trapped in a tunnel that turned out to be a dead end. However, the Australians pressed on and revealed, for the first time, the immense military significance of the tunnels. At an international press conference in Saigon shortly after Operation Crimp, MacGregor referred to his men as Tunnel Ferrets. An American journalist, having never heard of ferrets, used the term Tunnel Rats and it stuck. Following his troop’s discoveries in Củ Chi, Sandy MacGregor was awarded a Military Cross.

View of kitchen area within the tunnel system

From its mistakes and the Australians’ discoveries, U.S. command realized that they needed a new way to approach the dilemma of the tunnels. A general order was issued by General Williamson, the Allied Forces Commander in South Vietnam, to all Allied forces that tunnels had to be properly searched whenever they were discovered. They began training an elite group of volunteers in the art of tunnel warfare, armed only with a gun, a knife, a flashlight and a piece of string. These specialists, commonly known as “tunnel rats”, would enter a tunnel by themselves and travel inch-by-inch cautiously looking ahead for booby traps or cornered PLAF. There was no real doctrine for this approach and despite some very hard work in some sectors of the Army and MACV (Military Assistance Command, Vietnam) to provide some sort of training and resources, this was primarily a new approach that the units trained, equipped and planned for themselves.

Despite this revamped effort at fighting the enemy on its own terms, U.S. operations remained insufficient at eliminating the tunnels completely. In 1967, General William Westmoreland tried launching a larger assault on Củ Chi and the Iron Triangle. Called Operation Cedar Falls, it was similar to the previous Operation Crimp, however on a larger scale with 30,000 troops instead of the 8,000. On January 18, tunnel rats from the 1st BN 5th Infantry Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division uncovered the Viet Cong district headquarters of Củ Chi, containing half a million documents concerning all types of military strategy. Among the documents were maps of U.S. bases, detailed accounts of PLAF movement from Cambodia into Vietnam, lists of political sympathizers, and even plans for a failed assassination attempt on Robert McNamara.

By 1969, B-52s were freed from bombing North Vietnam and started “carpet bombing” Củ Chi and the rest of the Iron Triangle. Ultimately it proved successful. Towards the end of the war, the tunnels were so heavily bombed that some portions actually caved in and other sections were exposed. But by that time, they had succeeded in protecting the local North Vietnamese units and letting them “survive to fight another day”.

Throughout the course of the war, the tunnels in and around Củ Chi proved to be a source of frustration for the U.S. military in Saigon. The Viet Cong had been so well entrenched in the area by 1965 that they were in the unique position of locally being able to control where and when battles would take place. By helping to covertly move supplies and house troops, the tunnels of Củ Chi allowed North Vietnamese fighters in their area of South Vietnam to survive, help prolong the war and increase American costs and casualties until their eventual withdrawal in 1972, and the final defeat of South Vietnam in 1975.

Below is an excellent video all about the CuChi Tunnels and the bombing Campaign, it is a video produced by a tour company in Cu Chi Vietnam very informative it is 48 minutes long.

If you’d like to read another of my articles that tell about those brave US soldiers who entered these tunnels to investigate (Tunnel Rats) then please click on this link:

https://cherrieswriter.com/2012/08/04/the-vietnam-war-tunnel-rats-guest-blog/

This post, by Commander Webb, was featured on the website of “Naples Museum of Military History” on July 16, 2018. To view it and many other veteran and war articles, please visit them at:

https://naplesmuseummilitaryhistory.org/

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or change occurs on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

Great

LikeLike

Excellent

LikeLike

I was in cu chi May 68-69 with 3/4 CAV. Glad we spent more time out in the bush. Everyone used to wonder how they got inside the 5th wire. They were already inside it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was stationed with an rf pf Arvin unit in an outpost in cu chi for six months. Glad I made it home had no idea of the extent of these tunnel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Fantastic I was in Nha be i remember the bombing in 68-69 bless everyone of you guys for doing that job I’m sure you saved my life thank you

LikeLike

I was the original tunnel rat for the 25th infantry, company C, 1st battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment. I went there on ship from Hawaii 1/1966 with the whole Division. I searched and destroyed tunnels to clear a base camp and also cleared and destroyed tunnels in hobo woods, iron triangle etc. glad to be home!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, sir!

LikeLike

I was there 25th id in 1966 7tn Bld 11th arty

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. I was stationed in ch lia

LikeLike

It was hell for all those who had to go through then, Thanks for filling in the details

LikeLike

My father, CPT (at the time) Herb Thornton was known among US forces as “the Father of the Tunnel Rats,” having led the first organized US Army tunnel team during Operation Crimp in January 1966. He and many other brave tunnel rats are written about in Tom Mangold and John Penycate’s book, “The Tunnels of Cu Chi – The Untold Story of Vietnam.”

I was present when the authors first contacted my Dad about their plans to write their book and after the phone call, Dad sort of blew off the notion that a book would actually be published. As an aside, Dad often commented that the thing that scared him the most about going into the tunnels was having B-52 strikes in the area, fearing the tunnel might collapse on them.

LikeLike

Was stationed with 4th of 9th Infantry 25 division at Cu Chi 1970 heard about tunnels

From out side of wire into base camp didn’t think it was that elaborate , found a cache

By falling into a entrance, while tamping down Elephant grass in what looked like a deserted village had old rice and rucksacks ,

We flew in a shape charge and brought it’s

Roof down.

LikeLike

I was with “A” battery 3/13 artillery, 25th infantry based out of Cu Chi from 10/1/1968 to 12/1969. I passed thru Cu Chi when I went on RNR other than that I was in the area near Trung Lap. Had many fire missions supporting troops in that area. Also went out on direct fire missions trying to destroy some of those tunnels. I don’t think we did much good the tunnels were just too big. Good article and informative video.

LikeLike

Good, but you left out where the 62 nd LANDCLEARING BATTALION in 69-70 leveled Cu Ci, Ho Bo Woods xnd thr Iron Trisngle . Thank you very much !!

LikeLike

I have a picture of my brother Lonnie Robbins coming out of one of those tunnels ten minutes before he was KIA in the Ho BO woods of Chu Chi. I have spoken to the solider and the medic that was with him. These were the bravest of the brave.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was stationed with the 25th in Cu Chi in 1969-1970 and was amazed to find out about the tunnels and how they were used up until the end of the war. It seems that we could never keep them out. I was in a helicopter repair unit and often rode shotgun on the truck that went to Saigon to pick up parts. Saw a lot more than I want to remember and was happy to make it back. I have to add, I disagree with oneoldokie1 on his final comment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I personally never got near or saw, any of those tunnels. I did while there, hear about them. I was in transportation. We had 1/2ton to 5ton trucks. We hauled various types of cargo from the Port of SAIGON, to many outlying Combat Bases. After havin been in country for almost 6months. My Company, the 543d TC. merged with the 572d TC. Then we took all trucks & equipment to, the Port Of Saigon. And a few days later, we 2 Companies boarded C-147z at TonSan Nhut, and flew north to a landing zone near Quang Tri. From the LZ, we went a few mles to an open spot & set up Camp. First thing we did was, set-up perimeter of defense. Then a few days later, all our trucks & eqiuipment arrived at, a port. We retrieved all the necessary trucks ETC then continued our daily duties. My last but not least word is, all AMERICANS who were killed in the NAM. They all died for, nothing. Say / Think, as you wish.

On Mon, Nov 12, 2018 at 6:22 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

> pdoggbiker posted: “The tunnels of Củ Chi are an immense network of > connecting underground tunnels located in the Củ Chi District of Ho Chi > Minh City (Saigon), Vietnam, and are part of a much larger network of > tunnels that underlie much of the country. The Củ Chi tunnels wer” >

LikeLiked by 1 person