John A. Lucas

This article clarifies the role of the Army’s 1st Cav Bravo Blues unit in Vietnam. The author, a former officer in the Blues, reflects on those soldiers who fought with him and died more than fifty years ago. It’s long, but well worth reading.

The Bravo Blues were part of the 1st Squadron, 9th Cavalry. 1/9 Cav was the reconnaissance arm of the First Cavalry Division. It had three Air Cavalry troops. Each was the reconnaissance arm for a brigade. I served with B (“Bravo”) Troop (B/1/9 Cav).

The Air Cav troops of the Vietnam era were unique organizations in the history of warfare. Nothing like them existed previously. To my knowledge, none like them exists now. Each troop had four platoons – the Red, White, and Blue platoons, and Blue Lift. The colors are derived from the colors associated with different branches of the service. When addressing the platoon leaders for the Cobra, LOH, and Infantry platoons, no one ever called them by name or rank. They were always referred to by everyone simply by the color of their platoon.

Red is the artillery’s color. Thus, the Red platoon was our airborne artillery, and in 1970, it consisted of AH-1G Cobra attack helicopters. Each gunship was armed with pods of 2.75-inch rockets, sometimes a 20 mm cannon, and a turret under the nose that could house both a 7.62 mm Gatling gun (known as a minigun and capable of shooting 100 rounds every second) and a rapid-fire 40 mm grenade launcher. The miniguns fired so fast that you could not distinguish individual shots – they just sounded like a buzz saw. Bzzzzzzzzzzit. My estimate for the cyclic rate of fire for the 40 mm grenade launchers is about 120 rounds per minute, or two grenades per second. Bap, bap, bap, bap. The pilots could choose which weapons to have installed in their turrets. Some opted for two miniguns, but most had both a minigun and a grenade launcher. These were fired by the co-pilot, who sat in the front seat.

The scout or White platoon consisted of OH-6A scout helicopters known as “little birds” or LOHs (for “light observation helicopter”), pronounced “Loach.” A LOH normally flew with a crew of two – a warrant or commissioned officer pilot and a sergeant who served as the gunner. Being a gunner on a LOH with the 1st Cav was about as high-risk as it gets. The gunner sat in the door opening behind the pilot. There was no seat; his legs dangled over the edge of the bird. By today’s standards, a LOH gunner was a low-tech weapon system – he had an M-60 machine gun and a wooden box filled with explosive, smoke, and white phosphorous (WP) grenades. My friend Jon Swanson was “White” for much of my time with B/1/9. Jon was killed in Cambodia on February 26, 1971, along with his gunner, Larry Harrison, in an action for which Jon received the Congressional Medal of Honor and Larry the Silver Star. Good men, both, and sorely missed.

The Blue Platoon was an infantry platoon with blue as its color. I led the Bravo Troop Blue platoon, also known as the “Blues.” The “Blue” just prior to me was my friend Mike Nardotti. Mike was a stud, no doubt about it. He was my classmate at West Point, where he was an All-American wrestler (recently inducted into the National Wrestling Hall of Fame. No one messed with Iron Mike. Mike was wounded pretty badly and evacuated back to the States. But he recovered and ultimately retired from the Army as a two-star general. The young lieutenant who replaced me at the end of my tour was also badly wounded and had to be medevac’d back to the States with very serious injuries. I was lucky. Of the five lieutenants whom I knew about who led the Blues in 1970 and 71, I was the only one who was not evacuated on a stretcher. There were others; those are just the ones I know about.

The Blues were a heavily armed and aggressive group of men. Mike had trained them well by the time I took over. Being in the Blues was a sufficiently high-risk activity that no one was forced to join. Everyone was a volunteer – you had to volunteer to be in the Blues. When I say that the Blues were heavily armed, that is an understatement. Although we were only one small platoon, we had almost as much firepower as a line infantry company with 100+ men.

I took 21 Blues on operations every day. That number was dictated by the lift capacity of our UH-1B “Huey” helicopters from Blue Lift. We had three Hueys available every day. They flew only for us and the Ranger LRRP teams.

Our three Hueys could each carry seven men, plus their crew: a pilot, co-pilot, and two door gunners. When carrying a fully loaded infantry company, however, they could usually carry only 4 or 5 men. That was because the line infantry companies were typically inserted for two to three weeks of operations and carried full rucksacks, with much more gear, food, and water than we did. In contrast, we typically only carried one or two one-quart canteens, our personal weapons, and all the ammunition and grenades that we could manage. We did not carry shovels, multiple days’ worth of food and water (which were necessary during the dry season), mortar and mortar shells, claymore mines for night defensive positions, or other gear that a regular infantry company would typically carry.

Because a typical rucksack carried by a line infantryman, with food, water, and lots of ammunition, weighed around 75 pounds, if you put five fully loaded grunts in a Huey, the extra weight would be about equal to an additional two more lightly loaded troops. So, by going light, we could load two more fighters on a Huey for a total of seven (plus the crew of four).

The Blues were divided into three 6-man squads plus a three-man “headquarters” element consisting of Blue, the platoon sergeant (“Blue Mike”,) and an RTO. Each six-man squad was built around two three-man fire teams. Each fire team consisted of an M-60 machine gunner, a rifleman, and a rifle-grenadier who carried an M-203, a standard M-16 rifle combined with a 40mm grenade launcher. Our 21-man Blue platoon was equipped with six M-60 machine guns, six 40mm grenade launchers, and fifteen M-16 rifles.

As I said, we had plenty of firepower. Some guys also carried specialized personal weapons. One

sergeant always carried a sawed-off M-79 grenade launcher. It had the stock sawed off, leaving only the pistol grip and a shortened barrel. The whole thing, fully loaded, probably didn’t weigh more than two pounds. Plus, we had our birds overhead with their added firepower.

Even though 1/9 Cav was denominated as the division’s reconnaissance unit, it didn’t just do recon. They fought. The tactics were built around the “Pink Teams.” Combine a Red bird (Cobra gunship) and a White bird (LOH), and what do you get? Presto! A PINK team! Throw in an attached squad of Blues on a Huey is flying with them, and what do you get? (Hint: Red + White + Blue) A Purple team (I know, groan)! The Pink team typically operated with the LOH flying at tree-top level just above the triple canopy jungle.The pilot would use the rotor wash from the helicopter blades to blow aside the treetops and foliage, allowing him and the gunner to see down into the jungle below. If they saw something, they shot it up (we always operated in free-fire zones), marked the target with a smoke or WP (white phosphorous) grenade, and got the hell out of the way so that the Red bird could roll in with its rockets, cannon, and heavier firepower.

The Blues had three common missions. The most typical was to be inserted by air (or sometimes by rappelling down ropes from a hovering helicopter) when a Pink team found something. That

“something” could be anything from unfriendly people with AK-47s who took offense at the snooping of the Pink team, to a freshly used trail or bunker complex that indicated an enemy unit in the area.

The second most common mission was as the quick reaction force (“QRF”) for the Ranger teams. The Rangers, or LRRPs (for Long Range Reconnaissance Patrols), operated in four- to six-man teams. Their mission was to operate deep in the enemy’s area, far from US units and usually beyond the protection of US artillery. The Ranger company was commanded by my friend, Pete Dencker. Pete was also my classmate at West Point, where he played on the varsity football team. Another stud.

Because they were so small, if a LRRP team made contact with the enemy, they could get in hot water quickly. Often, their first contact with the enemy would come in the form of a sudden eruption of heavy gunfire in the dense jungle, from 15 to 50 feet away. Due to the lack of visibility and chaos, they often might not initially know if they were facing three, thirty, or three hundred enemy soldiers. They didn’t have the luxury of waiting too long to find out. Their immediate protection was the QRF — the Blues. The Blues could be on the Blue Lift Hueys and en route to the Rangers within about 1 minute of receiving the radio call. The Blues got into a lot of fights by assisting the Rangers. It was on just such a mission on December 6, 1970, that Iron Mike was seriously wounded, both by RPG (rocket-propelled grenade) shrapnel in the neck and back and a gunshot through the arm. After being wounded, Mike crawled forward under fire to pull back a severely wounded Ranger. Mike was later awarded a Silver Star and was inducted into the Rangers Hall of Fame for his actions that day. The Ranger he tried to save was SGT Omer Carson, who died of his wounds the next day.

SGT Omer Carson, RIP (Photo from Faces on the Wall)

I took over the Blues in December 1970 after Iron Mike’s wounding and evacuation. One of my first unconventional missions was the second night I was in the unit. Several of the officers and men decided that Iron Mike needed the chance to say goodbye to his Blues, even though he was hospitalized with serious wounds. I was asked to join the group, so we got in a Huey and went to the Long Binh hospital. There, with zero authority, we nonchalantly made our way to the ward where Mike was bedridden. With Mike still in his bed, we wheeled him out of the hospital and loaded him into the waiting Huey. Then we flew back to Bearcat so he could say goodbye to his Blues. After Mike became a general officer, I sometimes enjoyed telling other soldiers how I had once helped General Nardotti go AWOL.

The other most common mission — although thankfully less frequent than the first two — was going to the assistance of pilots and aircrew who had been shot down. If a helicopter was shot down, the small crew deep in Indian country needed help fast. Blues were on the way pronto. When LRRP teams or downed aircrews were in trouble, they often weren’t near a landing zone that could accommodate helicopters. That could mean that the Blues had to rappel into the contact area. Today, the Rangers and Delta Force “fast rope” out of the aircraft to get to the ground quickly. That is much more efficient, but back then, the Blues had to rappel, so they always carried gloves, a carabiner, and a short rope to make a “Swiss seat” for rappelling.

When I arrived, I heard a lot about a soldier who was on extended leave at the time. His name was Ken Perry. I think that it was Perry’s second or third extension, which meant that by the time he was killed in December 1971, he had considerable time in combat, with no time “in the rear with the gear.” When I got to the unit, the men told me about Perry, and it was all along the lines of, “Wait till you meet Perry. He is incredible.”

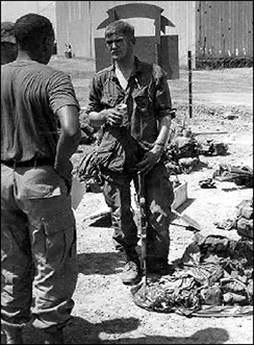

L. to R., Blue (John Lucas), RTO Dwight Craddock, Ken Perry, and Brawley.

Before Perry returned from leave, I heard lots of stories about him from the other Blues. It is not an exaggeration to say that he was a legend in the unit. One of the first things I remember hearing about him was that other troops called him Genghis Perry or the Savage Mongol. That was because Perry identified as a pure warrior and wanted to be like one of the feared members of Genghis Khan’s Golden Horde. When he took his 30-day extension leave, instead of flying home to California or going to one of the R&R destinations favored by young bachelors, such as Australia or Bangkok, Perry went to Japan. The Blues were all convinced that it was because Perry wanted to go to another Oriental culture, which he thought was as close as he could get to Genghis Khan’s empire, and Japan was the only place he could visit that was anywhere close to Mongolia.

When Perry returned from his leave, I was his platoon leader for the next 8 months. He was the most aggressive soldier I had ever encountered. He was absolutely fearless, at least as far as anyone could tell. With all his extensions, he had more combat experience than anyone, except our Montagnard scout, Dieu Luong.

My favorite recollection of Perry was from one day, sometime in 1971. He often walked point because that was where initial contact with the enemy was most likely to occur. Walking point in a combat zone when you can come under fire or spot the enemy any second, will definitely get your adrenaline going. I would rotate the point squad so that each squad walked point only every three days. When it was his squad’s turn, Perry always wanted to be the lead man on point. Right at the tip of the spear. One day, he came to me and told me that he didn’t want to walk point anymore – he wanted to walk “drag.” You could think of it as being “in the rear,” although “the rear” typically meant that at first you were maybe 50 yards or so from the people shooting at us.

I thought to myself that Petty had been in combat for going two years or more, had paid his dues, and if he wanted to walk drag, I would let him. But I did ask him why he wanted to change. His reply floored me. He said, “Well, Blue, I like to run through the fire. We usually make contact at the front, and if I am in the back at first, it gives me more distance to run through the fire to the point of contact.” That was Perry in a nutshell – where most people’s instinct when coming under hostile fire, especially from automatic weapons at short range, is to hit the ground or seek cover, Perry wanted to run through the fire. Like I said, Perry was afraid of nothing.

In the early 70’s, the Army in Vietnam was beset with racial problems and strife, particularly in rear areas. I did not experience any racial issues in the Blues, but when we returned to our rear base area (usually in Bearcat) after being in the boonies all day, the situation with the rear echelon troops could be different. There was a lot of racial tension, even murders, in the rear areas.

My tour ended, and I returned home in September 1971. Perry was killed three months later, on December 2. I don’t know the details of the fight, but I have little doubt that he was killed while running through the fire. I understand that the lieutenant who replaced me as Blue was seriously wounded that day, and another sergeant from the Blues, Schyler Watts, was also killed.

RIP SSG Schyler Watts, March 2, 1945 – December 2, 1971

Years later, I found Perry on the website “Faces on the Wall.” It is essentially an electronic replica of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. It includes photos of the KIAs, along with comments and remembrances from family, friends, and even strangers. I ran across a thoughtful remembrance of SGT Ken Perry from one of his high school classmates, named Ken Reeves. Here is what he said: “Ken was bullied and made fun of and treated like he was mentally challenged. I can only hope that those guys will recognize his ultimate sacrifice and realize this man was a hero. He rose through the ranks of the military and distinguished himself. I was one of those who sometimes made fun of Ken, and yet, I am not a veteran. I have lived a decent life, but I remember Ken and I think how I wish I could shake his hand and apologize for being a stupid kid who didn’t consider the real character of a dedicated soldier and a person of tremendous qualities who served his country for me and so many others could live on. Bravo to you, Ken. All these years, I have thought of you and appreciated you. Rest In Peace. Thank you for your sacrifice.”

RIP Ken Perry, Nov. 16, 1950 – December 2, 1971

And I say, thank you, Ken Perry, Schyler Watts, Omer Carson, Jon Swanson, Larry Harrison, and all of you who sacrificed so much. I love you all.

This author contributed earlier articles on this website. If you want to check them out, click on the links below:

https://cherrieswriter.com/2025/06/28/courage-and-coolness-in-a-pressure-cooker-a-vietnam-war-story/

Bravo Blue is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber: https://substack.com/@johnalucas6/posts

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

I was a 1st Cav LRRP ’68-’69. It was always good to know the Blues were ready to jump in when things got interesting.

LikeLike

Sorry Ken Perry, blame my old age no disrespect.

LikeLike

RIP Let We Forget, Mike Perry

LikeLike

Thank you.

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

Well written!

I knew an enlisted “Iron Mike” M60 “Hog” gunner during my two month stint in the AMERICAL walking point for 2Plt C Co 1-20 11 Bde – NOT in rotation. I was willing to risk going first every day because I felt most qualified philosophically – I was an existentialist. I knew also from hiking the Tetons with the Sierra Club 2 years before that weight was going to be a consideration; the SGT negotiated the deal that allowed me to carry no common gear or extra ammo, and privileged me with an air mattress (usually a “no-no” in the Bush).

Iron Mike was always willing to walk second slack, right behind SGT. What a comfort he was! I remember that part of one ear was missing: shot away during his baptism of fire. Guess he thought he led a charmed life.

We both stood down in early October when AMERICAL went back to the World, but I wasn’t short enough to DEROS.

LikeLike