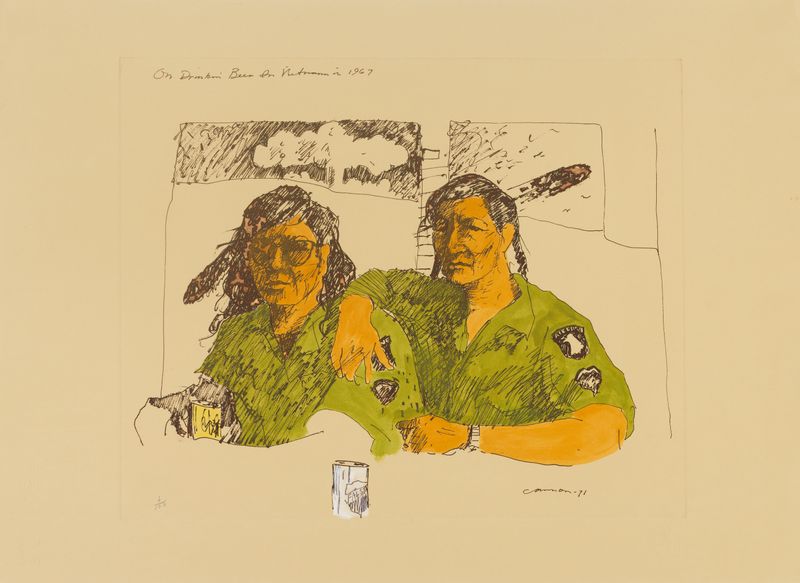

T. C. Cannon (Caddo/Kiowa, 1946–1978), On Drinkin’ Beer in Vietnam, 1971. Lithograph on paper, 48 × 76 cm. Collection of Museum of Contemporary Native Art.

This print depicts the artist and his friend from home, Kirby Feathers (Ponca), at a Vietnamese bar. Though stationed just miles apart, they only met once in Vietnam. Cannon was conflicted by his service; a mushroom cloud—a symbol of that conflict—appears in the background. Cannon was a member of the Kiowa Ton-Kon-Gah, or Black Leggings Warrior Society.

Approximately 42,000 American Indians—one of four eligible Native people compared to about one of twelve non-Natives—served in the armed forces during the war in Vietnam (1964–1975). Many were drafted, but many volunteered, often citing family and tribal traditions of service as a reason.

Native Americans served valiantly in the Vietnam War as they have in all of the United States’ conflicts.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Department of Defense did not keep records on the numbers of Native Americans who served in the armed forces, but scholars estimate that as many as 42,000 Native Americans served in the Vietnam War. Unrecognized by the Department of Defense or service branches, these Native American servicepeople were sometimes mislabeled as whites, Latinos, or even Mongolians. Although exact numbers are impossible to verify, some studies find that Native Americans were more likely to serve in combat units. One assessment of 170 Native Vietnam veterans found that 41.8 percent of those surveyed served in infantry units, while nearly another quarter served in airborne or artillery units. Several sources insist that 232 Native Americans died in the Vietnam War and are listed on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC.

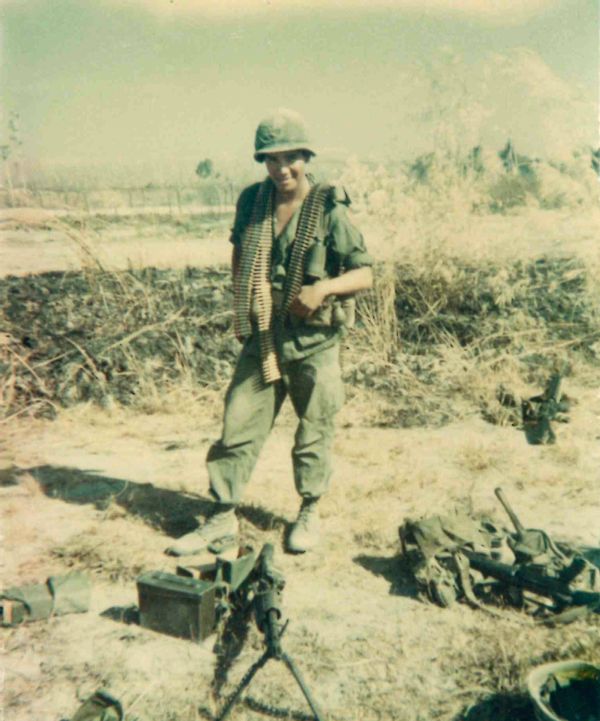

Courtesy of Harvey Pratt

Harvey Pratt (Cheyenne and Arapaho, b. 1941) holds a Naga knife—a Southeast Asian knife used for cutting through vegetation—during the camouflage and evasion portion of ambush training for his service in Vietnam in 1963.

Motives for Service

Native Americans enlisted or accepted induction into the military during the Vietnam War for a variety of reasons. Patriotism and concern for democracy’s survival in the Cold War inspired many Native Americans in the same ways that these motivations affected members of all races and ethnicities in the United States. Other sources of inspiration may have been more specific to Native communities’ traditions and cultures. Historically, in Native societies, most men share the collective responsibility of protecting the tribe or community from outside aggression. Native American beliefs commonly insist that military service and the experience of combat steels young men, transforming them into future leaders. Proximity to danger, violence, and death, these traditional views maintain and implant wisdom, acumen, and respect in those who pass the test of combat. Furthermore, in some Native communities, traditional practices require that men demonstrate martial and religious prowess to be considered full-fledged members of the nation.

During the Vietnam War, young Native Americans surely heard stories of their fathers’ and grandfathers’ service in the world wars and Korea, and they viewed the conflict in Southeast Asia as their opportunity to demonstrate prowess and earn the esteem of their elders and peers. Moreover, some Native societies traditionally afforded young, unmarried men little social prestige within the tribal community. For young men in these environments, military service offered an opportunity to escape their hometown and return as an independent and mature member of the tribe or community.

Potawatomi Traveling Times

Ernie Wensaut (Forest County Potawatomi, b. ca. 1945) checking his gear before a patrol mission near the Cambodian border in the highlands of Vietnam in March 1967. A member of Company C, 2nd Battalion, 10th Infantry, 1st Division (also known as the “Big Red One”), Wensaut was an M-60 machine gunner whose weapon, nicknamed “The Pig,” fired 500 to 600 rounds per minute.

Additionally, some Native Americans may have enlisted or accepted induction because they believed they owed service to the United States due to treaties that their nations had concluded with the Federal Government in the past. These individuals likely acknowledged that the United States repeatedly broke its treaty promises with Indian nations, but members of these nations may have remained committed to upholding the alliances their ancestors had made with the United States. Lastly, there surely were some Native Americans who volunteered for military service during the Vietnam War to escape poverty and the lack of opportunities in the cities, small towns, and Indian Reservations where they lived.

“Indian Scout Syndrome”

In Vietnam, Native American servicepeople faced racist attitudes held by non-Native officers and enlisted men. Some scholars have labeled this prejudice “Indian Scout Syndrome.” This racist caricature, which existed long before the Vietnam War, assumed that Native Americans possessed superior senses and an instinctive understanding of nature. Therefore, all Indians were natural scouts, trackers, or snipers. This stereotype sometimes led to higher numbers of Native Americans being assigned to the most dangerous duties in combat units, such as having to “walk point” or go on reconnaissance patrols. Some Native Americans embraced this warrior image and volunteered for the most dangerous missions.

Sergeant Billy Walkabout, a Cherokee from Oklahoma who served as an Army Ranger with the 101st Airborne Division, was the most decorated Native American serviceman in the Vietnam War. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for heroic combat actions outside of Hue in November 1968. Although numerous Native Americans, such as Walkabout, took pride in the warrior ethos, many Native Americans likely fell victim to a different type of discrimination.

Accounts from Vietnam reveal that some officers assigned Native Americans to the most mundane and menial tasks as a result of stereotypes that regarded Indians as untrustworthy, lazy, or stupid. Anxieties prompted by cultural and racial differences between the Americans and Vietnamese even found their way into the Vietnam-era parlance used by service people. Firebases were colloquially known as “Fort Apaches,” and former Communists who chose to collaborate with the South Vietnamese or Americans were “Kit Carson Scouts.” The phrase “Indian Country” referred to remote areas in the Vietnamese jungles and mountains infested with the Viet Cong or North Vietnamese. Patrols in “Indian Country” likely meant ambushes and booby traps, and since these encounters happened far from urban areas, media reporters, and high-ranking officers, the normal rules of engagement sometimes were believed to be suspended.

In one study, some Native American veterans expressed dismay that atrocities they had witnessed in Vietnam’s “Indian Country” mirrored crimes the United States government had committed against their own people. To some observers, the war in Southeast Asia resembled a foreign invasion in which outside militaries targeted civilians, stole land, and resettled survivors in refugee camps. Meanwhile, some Native servicepeople expressed sympathy for indigenous Montagnard peoples, who wished to maintain their independence, practice their traditional lifestyles, and remain outside of the conflict. Native American cultures often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat

Native American societies often practice traditional martial rituals for warriors before they depart for war and when they return from combat.

Cultural Attitudes and Practices in War

These practices existed long before the 1960s—there are accounts of similar rituals during World Wars I and II—but Native Americans continued these traditions during and after the Vietnam War. Numerous nations require veterans to perform ceremonial and religious functions at powwows and tribal gatherings. In many cases, older males count coups or recount stories of martial prowess to reinforce tribal solidarity, language, history, and identification with the homeland. Other ceremonies mark the transition from war to peace and vice versa. The Navajo, for example, have been known to perform a dance ceremony called the “Enemy Way” for members of the tribe on their departure and return from war. This ceremony reenacts a traditional story as a means of suspending the rules prohibiting violence before the warrior departs, and it restores the rules of peacetime upon the warrior’s return. Navajos and Cherokees employ similar ceremonies intended to exorcise the demons of war from those reentering the peaceful community. In other nations, medicine men or shamans perform rituals to help individuals heal the scars of combat or protect loved ones at the front. Elders and parents often provide gifts and tobacco and say prayers to ensure protective medicine watches over warriors when they are away. Although servicepeople in the Vietnam War departed and returned at different times, evidence suggests that Native American communities continued to employ traditional ceremonies throughout this era. The practice of certain rites and traditions may have become more widespread after the war as a result of the hardships suffered by Native service people in Vietnam.

Courtesy Donna Loring

Donna Loring, 1966.

Loring (Penobscot, b. 1948) served in 1967 and 1968 as a communications specialist at Long Binh Post in Vietnam, where she processed casualty reports from throughout Southeast Asia. She was the first female police academy graduate to become a police chief in Maine and served as the Penobscots’ police chief from 1984 to 1990. In 1999, Maine governor Angus King commissioned her to the rank of colonel and appointed her his advisor on women veterans’ affairs.

Native American veterans of the Vietnam War stand in honor as part of the color guard at the Vietnam Veterans War Memorial. November 11, 1990, Washington, D.C. (Photo by Mark Reinstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Coming Home and Recovery

Several studies have found that Native Americans suffered from the physical and psychological traumas of combat at higher rates than other servicemembers following the Vietnam War. Poor employment prospects on reservations and in rural areas, combined with inadequate access to medical and psychological care, exacerbated the problems many Native veterans faced. A widespread reluctance to speak with outsiders or admit to shameful behavior or conduct encouraged some Native American veterans to forego programs designed to help them cope with the traumas of combat. Several sources indicate that alcoholism and substance abuse among Native American Vietnam veterans was widespread, especially during the first two decades following the conflict.

The United States government failed to devote special attention to the plight of Native veterans until the 1980s. Despite these difficulties, the Vietnam War inspired many Native American veterans to reconnect with their cultures and reinvigorate their communities. The war and emergence of social justice movements politicized Native veterans in new ways, and many veterans became active in tribal governments and cultural associations. During the decades following World War II, the Federal Government slowly eliminated many aspects of tribal sovereignty during a process named Termination. The goal of Termination was to assimilate Native Americans into mainstream American society by breaking up the reservations. Native Americans resisted these infringements on their rights by strengthening tribal governments, protesting injustice, battling these policies in courts, and restoring tribal customs, languages, and education. Historians have labeled this period of Native activism the Red Power movement. Many Native activists who took part in the 1970s Red Power movement were Vietnam veterans, including a large number of the American Indian Movement (AIM) protestors who organized the Wounded Knee standoff against federal law enforcement agencies in 1973. This violent occupation and standoff resulted in a 71-day siege and the death of two protestors.

Most Native Vietnam veterans, however, affected positive change through peaceful methods. They took on prominent roles in tribal councils on reservations or became participants in cultural or social justice organizations in towns and cities. Some of the most prominent of these voluntary associations are known as warrior societies, which were established by many nations and tribes throughout the United States and Canada during the 1970s and 1980s. In many nations, such as the Kiowa, Comanche, Lakota, Chippewa, and Cheyenne, certain tribal functions can only be performed by veterans. Vietnam veterans have fulfilled and continue to serve in these leadership roles in the present day.

National Native American Vietnam Veterans Memorial, located at The Highground in Neillsville, Wis.

This post originally appeared on THE UNITED STATES 50TH VIETNAM WAR COMMEMORATION website: https://www.vietnamwar50th.com/assets/1/7/NativeAmerican_Posters_FINAL.pdf

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, and change occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

Thank you so much for this precious article. I am an American citizen and US veteran who is updating my novel about the Vietnam War (based on the real life testimony of a veteran who fought in Vietnam): I was drawn to this story of yours because the veteran who told me his story mentioned a soldier he worked with in Germany who was called Cornsilk (in 1970), who was from a reservation in Oklahoma. My book sells online with the title ‘The World, the Flesh and the Devil’.

LikeLike

I hope you will consider this, even though it was published previously on my Substack.

If you like it, I have a few more.

https://johnalucas6.substack.com/p/a-vietnam-story-courage-and-coolness

John

https://johnalucas6.substack.com/

LikeLike

John, I just came across this message and plan to use your post as one of my weekly submissions on my website. Thank you for submitting. I’m most appreciative~ / John

LikeLike

Happy you liked it. I have some others that may be of interest. Is there a better email to use to send them to you?

thanks. John

LikeLiked by 1 person

john.podlaski@gmail.com

LikeLike

I served with two Kiowa in our Speical Ops team. To me they looked and acted no different than any other American boy who entered the war. Whether it was because of their heritage or natural ability, both were remarkable individuals, demonstrating almost magical abilities. But then again, all who I stood beside were amazing. Funny thing though, I never thought of their American Indian heritage when conducting a mission. In that case we would all sacrifice for one another to ensure no man was left behind. God bless every man and women who entered that dreadful place, and God bless America.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s another good example of really interesting information about our history without ignorant and biased media morons!

LikeLiked by 1 person

With the raw material not a bad job, but hiccupping back to “studies” was repetitive and boring. Some home grown stuff would have been better. As we all know, in the current state of sociology, all remains to be over turned.

LikeLike

thanks for the in-depth reporting.

LikeLike

Good article, In 1970 I was a m60 gunner in Quang Tri Vietnam. as an Army grunt. My assistant gunner was a full blooded Navago. He was a fine soldier and as good as any other race guy that I worked with. Roger later became involved with the Indian Affairs Dept of the state of Arizona. A good man.

LikeLike