This author provides a brief synopsis of just three hours in the life of one relatively unknown veteran in Vietnam. Well worth a read!

By John A. Lucas

During this Veterans’ Day week, it is fitting to remind ourselves that Veterans are among us every day. Most readers probably know some, perhaps many. Even so, there are many who have served with honor and distinction, but you would never know it. Any who have been in combat are typically not overly eager to tell their stories. Some things are better kept to oneself.

Despite that reluctance, however, know that veterans are everywhere among us. They are diplomats, doctors, and lawyers. They are brick workers, truck drivers, and electricians. They are people who make the country work.

Some have served in combat. Some have not. But all answered the call to serve the nation, and the surpassing majority did so with courage and honor.

Some people, no doubt, do not know many veterans, even if they are neighbors, customers, coworkers, or just someone encountered for a brief conversation in a parking lot. A manager at your local Home Depot may be a veteran of the bloody battles in Fallujah. Your administrative assistant’s father, whom you may have met only briefly, may have been decorated for heroism under fire in the terrible fighting in the Ia Drang Valley in 1965.

If you knew who these extraordinary people were, what they have seen and done, you would want to know more. So, this is my effort to fill that gap just a little bit by telling the story of some of the vets among us and what they endured on one night in Vietnam.

The account below tells the story about one relatively unknown battle and about people who are unfamiliar to most. But that is my objective. The surviving veterans of that night are spread across this country, and, for the most part, if we see them on the street, sit next to them on a train, or even meet and speak with them regularly, we have little or no inkling of what they have done in the service of our country.

And, frankly, many of them would prefer to keep it that way. But if you have the chance to draw them out in conversation, you may be glad that you did. But if you do, please ensure that any questions are appropriate and respectful. Don’t even think of asking, for example, “Did you ever kill anyone?” Anyone who wants to talk about such things is either a little unbalanced or, all too often, a big fat liar.

I am providing a brief synopsis of just three hours in the life of one relatively unknown veteran, which tells only a fraction of his and others’ stories.

August 24,1969, Thừa Thiên–Huế Province, Vietnam

In the early morning hours of August 24, 1969, a company of about 90 courageous soldiers from a highly trained, elite unit crept through the darkness to prepare for an attack on their enemies’ position. These men were members of an elite, highly trained unit, courageous soldiers all. Like the skilled professionals that they were, they had reconnoitered their target for several weeks. They knew the location of every enemy position and weapon. They even had sketches of individual soldiers on the base. They had repeatedly timed and measured the duration of certain activities in the enemy encampment. They rehearsed their assault over and over. Repeated rehearsals were necessary because they would attack under the cover of darkness in an effort to gain surprise and create maximum confusion and fear in their enemy.

Like the men of the 101st Airborne Division in the last hours before they parachuted into Normandy on June 6, 1944, these men knew that many of them probably would not live through the next few hours. Mouths were dry and hearts were racing as adrenaline pulsed through their bloodstreams. But, overcoming their fear and tension, they pressed onward to accomplish their mission. Like soldiers throughout the ages, they did it because of discipline buttressed by their loyalty to their comrades and friends with whom they would fight. And like soldiers of all time, some lived and some died.

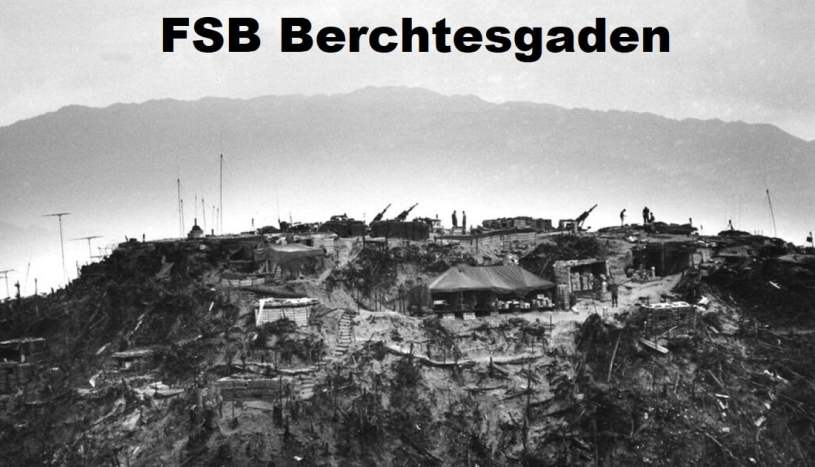

The attacking soldiers were members of a highly trained North Vietnamese sapper battalion. More died than they had anticipated or planned because their target was Fire Support Base Berchtesgaden, held by the men of Company B, 1st Battalion of the 506th Airborne Infantry. They were part of the famed “Band of Brothers” from the 101st Airborne Division, who had previously occupied Berchtesgaden, home to Hitler’s Eagle Nest. This is their story, as told through the eyes of a young platoon leader who had been in Vietnam for less than two months. His platoon bore the brunt of the North Vietnamese Army’s attack.

Here is his story, as told in his own words.

A Vet’s Story

Republic of Vietnam, 1969. I arrived in-country on June 28. After 3 days of orientation at Bien Hoa, I reported to my unit, 1/506 Infantry, 101st Airborne Division in I Corps. My company was based at Fire Base Currahee at that time, which was located in the Ashau Valley, a mountainous area west of Hue, not far from the Laotian border. As I got off the Huey, I saw about 10-12 body bags (with remains) ready to be picked up.

During July, we were in the “bush” conducting search and destroy operations, making sporadic contact every few days, usually brief encounters. We lost one soldier who was walking “point” when he was ambushed, sustaining an abdominal wound from an AK-47 round, which exited through his back. He remained conscious for the 30- to 40-minute period it took for a medevac to arrive. We learned the next day that he had died. Three or four other soldiers were wounded during the month, one of whom suffered his third wound (by AK-47) to his buttocks, after which he was assigned to the rear area at Camp Evans and did not have to return to the “bush.”

On another occasion, during a combat assault on a “hot” LZ (landing zone), the Hueys were not able to land due to nearby trees, so we jumped out from about 10-12 feet in the air. In the second Huey, one of the soldiers who carried the M79 grenade launcher jumped out, and when he landed, there was a loud “crack.” His femur had fractured (compound fracture). After securing the LZ, the platoon medic splinted the leg with an inflatable splint, and we called for a medevac. The medivac was able to land just barely avoiding the trees.

FSB Berchtesgaden and defensive planning – Hueys picked up B Company and flew to our new destination, Fire Base Berchtesgaden, located on a medium-sized hill (Hill 1030) in the general area where we had been in July. The company that had been there in July rotated out to the “bush.” My 1st platoon occupied the southwest section of the perimeter and had 8-10 bunkers for 3-4 men each, as well as a command bunker. All of these structures were fortified with sandbags, empty ammunition boxes filled with dirt, and topped with 4-to 6-foot-long steel planks.

We made daily improvements to the bunkers. To our front, the terrain sloped gently for 20-30 meters, then fell off more steeply and was no longer visible. Trip wires and triple concertina wire were inspected and improved daily. We set up claymore mines at dusk. Weapons maintenance and cleaning were done daily. Ammunition was kept as clean as possible and in plentiful supply.

Squad leaders, the platoon sergeant, and I were constantly monitoring these areas. After dark, the platoon sergeant and I made rounds of each bunker twice.

Every night at dusk, Company CO (CPT Roger John, graduate of Texas A&M ‘61, on his second tour) met with platoon leaders and First Sergeants to discuss the plan for the night. This included supporting artillery and air support, Cobras on station, “Spooky” and Huey gunships on station, etc. The plan also included 2-3 “mad minutes” at irregular intervals, typically at least 2-3 hours apart. [Author’s note: A “mad minute” was when all personnel opened fire simultaneously with all available weapons. The purpose was to catch any approaching but still undetected enemy unaware and inflict casualties, and disrupt a possibly planned attack.]

At our meeting on August 23, we discussed these plans, including the times of the mad minutes. Each night, our mad minutes would occur at different times, but we had developed a pattern of having them about 2-3 hours apart. At our meeting that night, the time of 0300 was chosen for a mad minute. I was concerned that the enemy may have picked up our pattern of waiting several hours before repeating a mad minute. I mentioned my concern about the pattern and suggested that we have another mad minute at 0315 instead of waiting several hours before the next one.

I returned to my platoon and continued making preparations for the night, including making rounds of our bunkers. Sometime around 0100, I returned to the command bunker where the platoon medic was situated. I took a short nap but awoke with a bad dream of sappers infiltrating our perimeter and overrunning our position.

The attack – At 0300 on August 24, the “mad minute” started. It was done in one minute without incident. All was quiet. At 0315, we began to fire the second “mad minute.” After a minute, most sectors began to get quiet. However, the bunkers on the left side of the perimeter (approximately 50-60 meters away from where I was located) continued to fire. The platoon sergeant was in one of those bunkers and reported there were “gooks in the wire,” just a few meters in front of the bunkers. They were firing AKs and throwing satchel charges, which they carried in a bag strapped to their body. I was in the command bunker at the time and radioed the platoon sergeant that I was coming over to his position to get a better idea of the situation.

On my way to his bunker, incoming mortar rounds began coming in all along our bunker line. Several hit quite close to me and caused me to lose about 95% of my hearing, leaving a loud residual ringing in both ears that made further radio communications difficult.

By this time, the platoon and company were on full alert, returning fire, detonating claymores, and throwing grenades. The night was very dark, without any moonlight. Trip flares provided some light. We immediately requested illumination rounds from the mortar section, and these were up within minutes. The two-man searchlight team turned on the searchlight. Coordination with CPT John was ongoing, and decisions were made for close artillery and air support. Mortars and rockets continued to fall on our positions.

With my RTO [Author’s note: [the RTO is the radio-telephone operator] I made my way to the left end of the platoon bunkers where the sappers were first seen. I sent the platoon sergeant back to the command bunker. Other bunkers were reporting receiving both small arms fire and satchel charges. One satchel charge fell into the bunker 1-2 meters in front of me, where two men were returning fire. One of the men shielded the other with his body as he reached for the satchel charge and threw it back toward the sappers. It exploded almost immediately, about just a few meters in front of them. That man continued to fight with great courage throughout the night and was recommended for the Silver Star for his actions.

Our platoon continued to return fire, and we soon had artillery and Cobra gunship support. We were able to coordinate directly with the gunships and give immediate feedback for fire adjustments. Our vision was much better now that illumination was in place.

About this time, we received word that a large NVA unit had been spotted on the other side of Hill 1030. Additional artillery fire was called in by CPT John. That area of the perimeter did not have sapper infiltration.

Our platoon continued to repel the sappers that were in front of us. Mortars and rockets continued for about 2-3 hours. Three men in the platoon were killed by a mortar explosion while they were carrying a wounded buddy up the hill to be treated by “Doc.” Twelve others were wounded and treated by our platoon medic. DOC was a CO (conscientious objector) and initially did not carry a weapon. After about a month in the jungle, he started carrying an M-16. During the several hours of the battle, Doc treated twelve wounded men with tourniquets, bandages, splints, IVs, and morphine. Any help from other soldiers was strictly OJT [Author’s note: On-the-job training]. I recommended Doc for the Silver Star. Several men had serious wounds. All wounded were evacuated later that morning. The Platoon Sergeant lost his foot when a mortar exploded on the command bunker. When contact ceased three hours later at 0616, a sweep of the perimeter revealed 31 enemy KIA, and various weapons, including 8 RPG [Author’s note: Rocket-propelled grenade] launchers.

An NVA lieutenant was captured. His notebook revealed a detailed drawing of our platoon area, including bunkers, the location of trip wires and concertina wire, and even observed behaviors of many of the men, such as who stayed awake, who slept, who listened to their transistor radios, and who spent time cleaning their weapons, among others. On one page was a drawing of a man with lieutenant insignia (me).

This author’s additional observations

The unnamed 1st Platoon Leader who penned the above recollection of the battle of FSB Berchtesgaden is a long-time personal friend. We were in the same cadet company at West Point.

It is doubtlessly true that his actions that night saved a number of American casualties. It is especially notable that, as a relatively new lieutenant in a unit that had recently returned from the massive fight at Dong Ap Bia, commonly known as “Hamburger Hill,” my friend had the good judgment and initiative to speak up and point out that the unit needed to change its established practice of conducting a mad minute at intervals of several hours. He correctly noted that the enemy might take advantage of the predictable lull when many soldiers were going back to sleep by stealthily infiltrating and launching their surprise attack. It was that unexpected mad minute, only 15 minutes after the prior one had concluded, that surprised the enemy, interrupted their attack, and doubtlessly saved many American lives.

His 1st Platoon was the focus of the enemy attack. They lost three killed and twelve wounded, for a casualty rate of over 40% in just three hours of fighting. If not for the unit pride, discipline, and competence of the 101st Airborne, AND my friend’s cautionary note about the mad minute, it could have been far worse.

Characteristically, when I told my friend that I wanted to write a short article about this, he asked that I not use his name. Similarly, both in talking about the fight and in memorializing his memories of it, he did not mention that he had been awarded a Bronze Star Medal for valor for his actions that night. I had to drag that information out of him.

He pointed me to the pictures below, which he discovered on the Internet, and told me that they appear to be part of his 1st Platoon perimeter on FSB Berchtesgaden. Take a few minutes to look at it and try to imagine what it was like to be a teenager there in the dark at 3:00 a.m., with 90 men trying their best to kill you. Just try it.

My friend did not make a career in the military but ultimately went to medical school and retired from his practice several years ago. I doubt that many, if any, of his former patients or staff have any inkling of his background. And that is sort of my point today — Veterans are among us, but, for the most part, we do not know who they are or what they have done. But they deserve our respect and gratitude, even if they are reluctant to share it, as is my friend.

The author has previously contributed articles to this website. If you wish to read another of his articles, click here: https://cherrieswriter.com/2025/06/28/courage-and-coolness-in-a-pressure-cooker-a-vietnam-war-story/

Bravo Blue is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber: https://substack.com/@johnalucas6/posts

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

In hindsight, it’s usually the small decisions that make the larger differences. Good call on the routine change up. Nothing we did that was repetitive ended well.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Gale Fechik. 1st ANGLICO

Story so vivid it is easy to picture. Any time I meet a Veteran that served before my service in country I thank them for “softening up the enemy “. Truly believe they served in “Hell” compared to my personal duty and by their diligence and sacrifice my duty was easier.

Again, from the bottom of my heart, I believe I’m here today due to the thousands of Vietnam Veterans that served and preformed with diligence to make sure as many as possible survived. Job very “Well Done”.

LikeLike

Good rendition

Been there survived—lost brothers

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good and accurate story about typical happenings in 69-69. As an advisor to an ARVN artillery unit, our firebase was subject to similar circumstances. My own experience, however, involved a “sleeper” who cut the wire on our firebase in Laos. Six hours of close quarters and “danger close” supporting American artillery resulted in 30 wounded or dead. My higher sent his personal bird to extract me under fire to a triage and the hospital ship offshore.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you

LikeLike