Imagine you are touring Italy and a stranger joins you at your table during lunch. After some small talk, he wants to share his Vietnam War experience with you. He has to tell his story, and you listen intently for the next two hours. Later, his memories will need to be paid forward.

How the traces of the Vietnam War never end.

By David Gerstel.

Two of the men in this story I never met. The third was a stranger who introduced himself in Sarnano. His name was Joe. We had drinks at an outside bar under a large umbrella in the medieval village, which I was

visiting as part of a slow food tour and introduction to Le Marche. We began with bruschetta, focaccia, and triangles of pecorino cheese with honey that ran to the edges of a black Japanese slate. I took notes on thin napkins. Our conversation lasted more than two hours, and he was sitting silently when I left, continuing to drink an excellent Rosso Piceno wine.

We discussed Sarnano’s history and character. I thought he was moving in the direction of an invitation to dinner, which I was expected to pay for. After the second glass of wine, he changed the conversation to the story of his life. Joe said, concentrating on the table, “The journalist Mark Jury died at the end of August of this year. I did not know him or The Vietnam Photo Book, but had seen his photographs in magazines long ago. “Vietnam”, Jury is quoted as saying in the NY Times obituary by Clay Risen, “caught up with me.” Our lives were touched by the news of his death and the reference to the passing in 2016 of Michael Herr, the author of Dispatches.

Joe: “I was at sea, east of Suez on an American Export Line vessel, the steamship Exemplar, in the summer of 1965. It was the India run, and we spent more time in Calcutta than New York, berthed at the Kidderpore Locks for so long that some crew had apartments and wives. This was my second or third India voyage after a year on passenger ships and time in the Med. My parents received a letter from the local Selective Service office. It would have to wait until the voyage ended. At 23 years old, I was a merchant marine officer on voyages to countries that few Americans cared about.

“The India ship paid off in New York on a Thursday, cash in our pockets, a great deal of cash. By law, we were paid in US dollars at the end of a voyage. Seamen are wards of the government, along with Indians. The government does not think much of either group.

“The letter was short. I could sail on ships to Vietnam or be drafted into the army. They had no reference. Door number 1, door number 2. I chose the first because the pay was better.

“The subway brought me to the operations manager’s office of the company in Lower Manhattan, from which you could see Miss Liberty. I waved to her every time we headed up the Hudson River to the company’s piers in Hoboken. Francis Xavier O’Bryn glanced at the letter with the government stamp and the signature of a clerk who decided the fate of men and boys he would never meet beyond their zip codes. He said there was a ship to Vietnam on Saturday. Two days between voyages. No time for a Broadway play. I went to the doctor to be vaccinated.

“We loaded at Hoboken and went coastwise to Philadelphia, Savannah, New Orleans, Beaumont, Texas for ordnance, tanks and bulldozers, beer and peaches, air conditioners and china dishware, condoms

and medical supplies, coffins; the necessities and accessories of war. Our voyage was going to take 6 to 7 months. I don’t remember if we went through the Panama Canal or around the Cape of Good Hope. It was a long way to the sound of cannons.

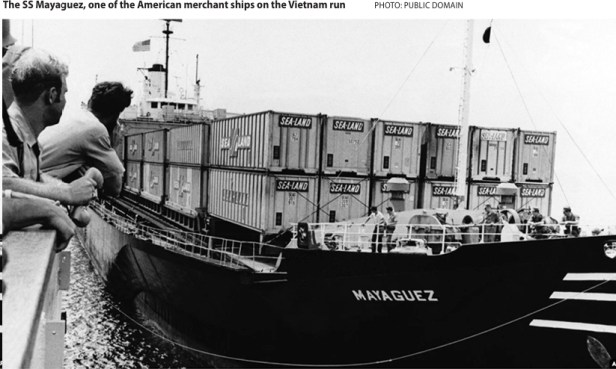

Michael Herr, author of Dispatches PHOTO COURTESY MICHAEL HERR

“Ships were in high demand and short supply that year. Every available freighter was chartered for Vietnam. The companies were going to make a fortune. Any mate, engineer, or seaman who could walk found a ship. Some had sailed in the Atlantic convoys to England and Russia from 1941 to the surrender of Germany. All the deck officers on my ship had unlimited master’s licenses and could have been in command. The crew was experienced with a few like me, young. Vietnam was a birthday cake with candles and gift wrapping. The North Vietnamese had no submarines and no aircraft to sink merchant ships. We were all going to make it through.

“Some Captains never drank, others never stopped. I sailed with one who was falling down drunk for six months without a day off, and every officer took the ship away at least once. Johnny Walker Red Label scotch was a dollar and a half, duty-free. In Saigon, the Captain closed the ventilators and ports to his cabin for fear of VietCong hand grenades. Never mind that the temperature reached 120 F and there was no air conditioning. We laughed. In that moment, we loved the war.”

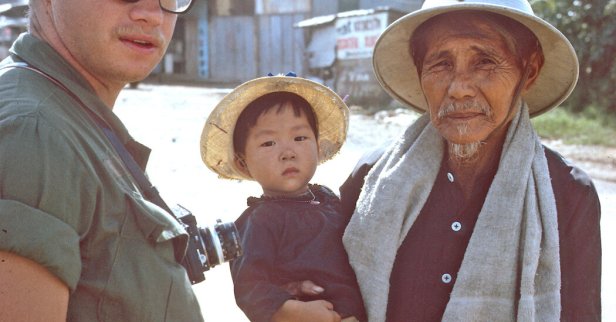

Mark Jury: According to his biography, he joined the army to become a combat photographer. He had no restrictions and went where he wanted, from the Continental Palace in Saigon to triple canopy jungle and rice fields, hot landing zones, search and destroy missions, and the Brown Water Navy. He took great and terrible photos, saw combat, and too many bodies. He ran towards the sound of gunfire. It took ten years for him to feel the effects of Vietnam. Then he began to drink and broke down.

Mark Jury – His stark photographs captured the Vietnam experience

Michael Herr: Late in 1967, according to the New York Times, he persuaded the editor of Esquire, Harold Hayes, to send him to Vietnam. It was shortly before Khe Sanh, one of the war’s bloodiest battles, and the Tet Offensive, a North Vietnamese campaign against targets in the South. Writing for a monthly magazine, Herr was an oddity in the press corps; one soldier asked if he would be reporting about what they were wearing, and the American commander, General Westmoreland, wondered if his assignment was to produce articles that were “humorous.” Yet he struggled. “The problem with Vietnam is that if your body came back, your mind came back too. Within 18 months of coming back, I was on the edge of a major breakdown. It hit in 1971, and it was very serious. Real despair for three or four years; deep paralysis. I split up with my wife for a year. I didn’t see anybody because I didn’t want anybody to see me.” It was writing Dispatches that brought it on, the memories and people asking about Vietnam. What he had seen went into the book, and there was nothing left. The first question is always: How many did you kill?

Joe: “I stayed in Vietnam for three years, back and forth across oceans. For the most part, it was easy, waiting to be discharged, watching the sunrise, and doing the job. That left time to lend a hand and fly supplies to fire support bases on C-130s from Da Nang, join the Koreans on sweeps through rubber plantations, be ambushed on the streets of Saigon and Cholon, or be killed in a cargo hold 50 feet below the freighter’s steel deck.

“Once or twice, I went out with American troops, pretending to be a warrior. We ran the river to Saigon under machine gun fire. None of it seemed real and I wanted more, a speaking role in the movie. I was a participant in the great adventure, excited and exhausted. I carried a union card with benefits.

“Vietnam was a roulette game. The bowl was dark and the hooded croupier dressed in black. All the segments on the spinning wheel were shadowed. The gamblers stood around, played with their cigarettes, gum, and weapons, and listened to rock and roll. You were not surprised when the ball stopped. It was continuous play, and your bet came up before the sun. No one wanted to win but you had to play. The newspapers at home had casualty lists bordered by thick black lines, but papers were not delivered to the casino. The notices were never read. Death was an empty space on the field.”

Jury and Herr wrote other books, but their lives were built in Vietnam. The tragedy, the legacy, even the laughter, was Vietnam.

Joe: “My war ended and other mates replaced me. I was back on the India run, done what the government said was my duty in the South China Sea, and carried the same germs of the disease that afflicted Jury and Herr. But I was unsure if it was Vietnam or dysentery from bad shrimp in Bombay at the Chinese restaurant near the Gateway to India that caused the pain. I worked the ship.”

In Vietnam, you learned caution and courage, deeply buried the dread that settled like fog in low valleys. Yesterday was gone and you forgot the day ahead. Some men wrote home every day, others never. They thought luck was with them. Until it wasn’t. Personal items were put into a cardboard box with a tag; socks and sweets were divided among the other men.

You did not realize when you came home that Vietnam was a finishing school for the remainder of your life. You weren’t smart enough for that. It made you different, tougher, more afraid and less. You pushed boundaries because Vietnam had none. You saw what men could do.

Joe: “Years later I left the sea and went far from the watery part of the world, work on the land carrying freight. Vietnam came with me. The infection continued to grow, invisible to an X-ray. Eventually, it would show a darkness on the negative held to light, but the terror on the edges was missed.”

Joe kept speaking, unwilling, unable to stop. I asked him why he was telling me all this. His answer was, “Because I will not see you again. Maybe the drinks and I needed to talk after I saw Jury’s obituary and read about Herr because I am tired and you are here, and there is no one else. Bad luck for you. And you are paying.” I was the audience and stenographer.

He said a few participants in Vietnam were fortunate and able to speak, Jury through his camera, Herr on a typewriter. Others had someone to listen to or say get over it, deal with it, and move on. Joe’s war was replayed in his car, at the stream where he fished, at breakfast in a diner with bacon and eggs, a baseball game on a windy day, in bed. There was remission from time to time.

Awareness came slowly; he changed jobs and cities, and abandoned friends. His wife left with the children, saying his war was behind her. Eventually, he bottomed out, gave up the companionship of men, and drifted away and downward. He had his devils, and together they visited his youth in the eastern seas, needing no guide or compass. The difficulty was returning.

He had to find a simpler world and so came to Italy, recalled from his days at sea, retreated to a village built on a rock one thousand years ago, and met a tourist in the historic center.

I had a room at the Hotel Terme off the Piazza della Libertà, which has tall trees and many benches, the statue of a priest paid for by a doctor in Toronto, and a bathing pool for birds. It is a peaceful spot. There is a memorial carved from Carrara granite that names the Sarnano men dead in the Nazi war. From the restaurant in the hotel, I ordered dinner, asking that it be brought to my room with a liter of wine.

My travels continued and I came back to Sarnano after two months. I had seen Ascoli Piceno, Urbino, the wonderful bronze horses in Pergola, and many other towns and villages. Asking for Joe, the bar owner said he had died in a fall, an accident late at night on the steep turning steps to the Piazza Alta

and the Chiesa di Santa Maria. I knew it was not accidental. He died of wounds.

It was a year before I understood what Joe had spoken about under a setting sun beneath the Sibillini mountains. I make an effort now to remember him, as well as Jury, Herr, and the others who lived that time. Joe’s life and memory have been paid forward, a good thing. I wish it could be more.

A quote on the internet, “Not everyone who lost his life in Vietnam died there, not everyone who returned from Vietnam ever left there.” Amen to that.

For Roni and Florence

David Gerstel is an American expat who has lived for many years in Sarnano, a small town nestled among the hills of the Province of Macerata, in the Italian region of Marche. It’s the middle of nowhere, but the center of everything.

dgerstel@securenet.net

This article originally appeared in THE AMERICAN, the transatlantic magazine July – August 2025/ Here’s the direct link:

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you’re interested in learning more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog to receive notifications by email or your feed reader whenever a new story, picture, video, or update is posted on this website. The subscription button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

This is wonderfully written. I’ve always considered myself very lucky to have lived a life relatively free of the Vietnam War’s worst torments – both physical and mental. But that’s not entirely true. Joe’s tale and this author’s description of it do a masterful job of describing the long term effects, thankfully without the details. Thank you Mr. Gerstel, and I’m sure Joe would thank you, too.

LikeLike

1st ANGLICO

May be a short read but it is packed with truth. Read it at least five times to absorb all the minutiae. The author states he “paid it forward “for Joe, the stories subject. It solidifies my experiences there. As too often uninitiated folks that’ll listen to my tales will give the “side eyed”glance suggesting the tales voracity. I do know my truths as they are indelibly tattooed in memory but time passes and one starts to question oneself. Thanks Mr. Gerstel and John for adding foundation to my memories.

LikeLike

xlnt and real.,

LikeLike

thank you.

LikeLike