I received this article from one of my blog followers who entered the US Navy after completing his medical internship. He served in Vietnam and witnessed a bombing raid on the Da Nang airbase in 1973. This is his memory of the event:

By Sidney W. Bondurant

I was a Navy medical officer in Vietnam. I finished high school in 1964. college in 1967, medical school in 1971, and my internship on 1 July 1972. I had thought that with all those 2-S draft deferments, I would have gone through the “Vietnam Era” without having to participate in the war. Didn’t work out that way. I had joined a Navy program called the Ensign 1915 Program while in medical school, since I needed the money and knew I would get drafted anyway after finishing my internship. That way, I got to choose the Navy and avoid the Army. My Dad had been an infantry company commander in the South Pacific in WWII, and I knew that the Army was not going to be my cup of tea.

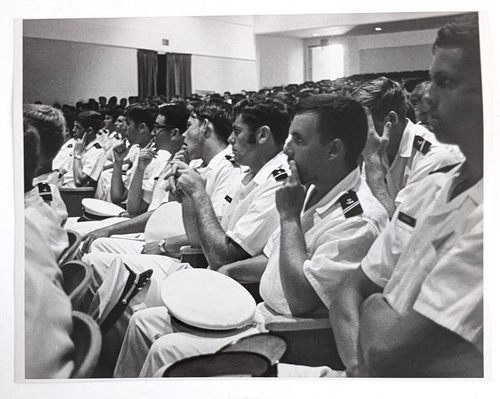

About six weeks before my internship ended, I got a big envelope in the mail with a set of orders telling me to report to Commander, Destroyer Squadron SEVEN no later than 0800, 3 July 1972. That gave me 48 hours to get from Sacramento (where I did my internship) to San Diego and transition from a civilian doctor to a US Navy doctor. When I got there I found my new boss and was told to go across the bay to Coronado to attend the “Orientation Course for Newly Commissioned Medical Officers” also know as “knife and fork school” since it was to teach us what we needed to know about our new life, its customs, etiquette, requirements, etc. It was a two-week course.

They had us in a classroom sitting at tables with a name plate on it, all in alphabetical order. The guy one seat over from me was named Brumfield. On Monday of week two, he did not show up. I leaned over to the next guy and said, “Hey, where’s Brumfield? This isn’t like college. You don’t get to cut classes here.” He looked at me, somewhat surprised, and replied, “You didn’t hear what happened? Some guy came up to him in the BOQ Friday night and handed him a set of orders. He’s probably in Saigon by now.” By Friday, half the class was gone, either in or on the way to Vietnam. That orientation course was all the “basic training” I got. I guess the Navy did not think we medical officers needed to know much past our medical education and skills.

I reported back to my unit after finishing the course and was told that we had been informed that we “Might have to deploy to Vietnam, but it would be maybe a year later.” Then it was, “We will definitely be going, but not until next winter sometime.” Then it was, “They have moved the date to this fall.” Then it was, “Pack your bags, we are leaving Sunday.” As the medical officer, one of my responsibilities was to be sure all the squadron staff were up to date on immunizations. I had been careful to do this, except for one staff member who had procrastinated. Me. I had to get a whole bunch of shots on Friday before our departure on Sunday. On Saturday, I had a temp of 101 and felt like I had gone a few rounds with Muhammad Ali.

On Sunday morning, I was aboard the USS Fanning (DE-1076) and underway for Vietnam. I had a lot of interesting experiences over there. Here is one of them:

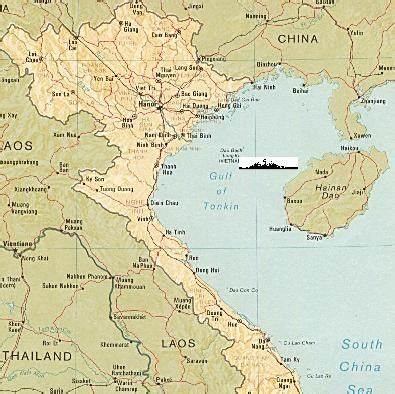

When the USS Fanning pulled into Subic Bay late in 1972, I got orders to immediately report to the Cubi Point airfield and fly to Da Nang, Vietnam. After a couple of days there, I flew out to the USS Reeves (DLG-24) at North SAR Station just off Haiphong, North Vietnam.

My responsibilities there were many and varied. Primarily, I was the Navy Search and Rescue medical officer required on board the Reeves when we would try to rescue pilots who had been shot down on bombing missions over North Vietnam. But if we were not running bombing missions on a particular day, I was the universal itinerant doctor to be used wherever needed in the Gulf of Tonkin.

That part of my duty had taken me back to the USS Fanning for something (I don’t remember what) for a day, and I was on board as the Fanning was pulling into Da Nang harbor to pick up and deliver the ship’s mail.

As the ship was sailing into the middle of the harbor, LT Mike Burt, CHC, USN (the chaplain), and I were on the deck sightseeing. Suddenly, there were explosions and smoke at the western end of the base, and the Fanning made a sharp 180-degree turn to head back out to sea. The CO of the Fanning did not know just what was going on but whatever it was, being in a confined harbor was not a good position for a warship to be in if it was going to get into a fight with some airplanes Getting out to the open ocean would give the Fanning more room to maneuver and defend itself. Mike and I ran back inside and got the story that Da Nang was under air attack. Flash radio traffic was flying from Da Nang around the world about an air raid on Da Nang. This had never happened before, although rocket and mortar attacks were a regular event every week. In fact, Da Nang was known to the troops as “Rocket City.” Everybody was trying to figure out exactly what was going on, but it was mostly confusion for a few minutes.

Over in Da Nang there was even more confusion. There had been a reported enemy rocket attack on Da Nang, and radar had thought it had pinpointed the enemy rocket launch site. There were several aircraft, F-4 Phantoms and A-7 Corsairs, in the air at the time, all armed with bombs, and the air controllers sent data to those aircraft to position them to bomb the suspected rocket launch site. It was an overcast day, and the pilots were all from bases other than Da Nang and were unfamiliar with the base layout and terrain. Well, somehow the data got garbled, and the planes were sent to bomb the South Vietnamese Air Force fuel farm at Da Nang Air Base. It was an all-service effort with USAF, USMC, and USN planes unloading 34 five-hundred-pound bombs on the fuel farm. It was a pretty spectacular sight!

Just as the bombs started falling, there was a Pan Am Airways charter flight on the runway going through its final preflight check before takeoff. Pan Am had the contract to deliver mail from the USA to Vietnam, and this was an everyday thing for this civilian aircraft to come into Da Nang, deliver the mail, then leave. When the bombs started falling, it was obvious to everyone on the base that the fecal material had hit the oscillating air circulation device. That Pan Am pilot was not about to hang around as the whole western end of the base was blowing up, so he shoved the throttle down and roared down the runway to get out to sea and away from Da Nang as fast as he could.

Out to sea about 25 miles or so, the USS Fox (DLG-33) was sailing to assume duty as PIRAZ station. PIRAZ stood for Positive Identification Radar Advisory Zone. It was the ship that acted as an air controller for planes heading into North Vietnam on bombing missions.

The Fox had powerful radars that swept the sky 24/7 and knew a lot about what was or what should be happening in the sky for hundreds of miles around itself. The nerve center of a Navy combatant ship is the CIC (Combat Information Center), and they were the first to really respond to what was happening in Da Nang.

“Combat to bridge. Captain, we have a contact, Skunk Alpha, coming out of Da Nang, moving slowly. He has no IFF.” All unknown contacts were called Skunks, and Alpha meant it was the first one of those seen that day. IFF was Identification Friend or Foe and was a signal all aircraft put out to identify themselves to military ships. Skunk Alpha was climbing slowly and turning from an easterly course toward a northeasterly course.

“Radio to bridge. Captain, we have flash traffic from Da Nang saying the base is under bombing attack. Multiple aircraft involved.”

“Bong Bong Bong” (sound) over the 1MC loudspeaker throughout the ship, followed by a voice saying, “General Quarters, General Quarters, all hands man your battle stations. This is NOT a drill.”

By this time, the Fox Commanding Officer, Capt. R. C Collins was at his GQ position in CIC issuing orders. The Executive Officer, CDR A. R. Heck, was now on the bridge at his GQ position. “Birds on the rails” was the first order, and four Terrier anti-air missiles went out from the ammo locker and onto the launch rails. “Prepare for missile launch.”

The slow-moving Skunk Alpha coming out from Da Nang had all the radar appearance of a Russian Bear bomber. It had not been seen before on the Fox radar, and the presumption was that it had flown low down the coast from North Vietnam, made a bombing run, and was now trying to get back to North Vietnam. It still had no IFF.

Fortunately, Capt. Collins was a pretty cool-headed guy, and his next question to CIC was, “Do we have any aircraft in the area who are in range to get a visual ID on Skunk Alpha?”

Combat to Captain, “Yes sir. We have an A-7 that can do that.”

Captain to Combat, “Get him going that way and give me a report as soon as he has him sighted.”

It was not too long before the A-7 Corsair pilot reported, “Skunk Alpha is a Boeing 707 with tail markings of Pan Am Airways.” Everyone in the USS Fox CIC had a kind of gasp and a sense of relief that their CO was a sharp, unflappable dude.

Captain to Combat, “Get on the frequency to the mail flight and ask him to check his IFF.”

Within seconds, Skunk Alpha was transmitting an IFF signal showing he was friendly. It was clear that during that rush to get out of Da Nang, the Pan Am pilot had failed to complete his preflight check, and one of the things omitted was the IFF check. He probably never knew how close he came to getting a Terrier missile into his Boeing 707.

It was a day of multiple “friendly fire” incidents. The Da Nang fuel farm was bombed, but fortunately, no one was killed. One guy broke both ankles jumping into a bunker to avoid the shrapnel, and some others had minor injuries. No aircraft were shot down, but one came really close to getting shot at with a missile that rarely missed. A lot of fuel was burned up.

Right after all this, I got sent back to the Reeves, and the next month I was transferred to the Fox. So I was a sort of participant and got the rest of the story from guys who were all involved in it.

I never heard if anyone found out who gave the wrong location for the VC rocket launch site or if the bomber crews got into trouble for the mistake. It was probably a series of mistakes, which made it harder to blame any one person for what happened. Fortunately, the commanding officer of a USN warship did not make the mistake of shooting down a civilian airplane. I doubt he ever got any recognition for that.

And that is the story of the Great All Service Air Raid on Da Nang. More information about the actual bombing and investigation can be found here: https://blackpony.org/dball.htm

Any of my readers witness this event? Please comment below.

*****

Thank you for taking the time to read this. If you have a question or comment about this article, scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video, or change occurs on this website—the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience. Before leaving, please click HERE and choose the one item that best describes you. Thank you in advance!

Very interesting reading. I suspect there are a lot of scenarios lke this one if all be told. would be hard not to happen with all the activity going on.

LikeLike

LikeLike

Interesting reading long story kind of sounds much like when Camron Bay was hit and blown up back in 1969 as a board LPH landing platform Hilo The time the Cam Ranh Bay would be blown up we sit out in the harbor and watch the ceiling getting blown up wondering why we weren’t doing anything to help wasn’t wasn’t able because we had no way to get out there and help but yet we could hear the conflict going on over there over the radio

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wasted my time reading it. You are a joke.

LikeLike

Interesting back story about a Navy medical officer’s introduction to Vietnam and the confusion of war (aka the fog of war). One mistake followed almost by another diagnosed by a commander who knew enough and had time enough to double check on the identity of a possible target. His cool head avoided spoiling the afternoon for the mail delivery plane.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative A long time after the war’s end I learned of a friendly fire incident. It was between a B-57 Bomber of the 8th or 13th Bombardment Squadrons ( I was a ground weapons crewman for both well before the incident) and a U.S. Coast Guard Cutter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Humans make mistakes. BB’s or A Bombs. Enemies or Friendlies. No plan is perfect. Thank God that tragedy was avoided.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Written very factually. S**t happens. The CO kept his cool. That’s the guy you want leading you.

LikeLiked by 1 person