High school kids in the 80s didn’t have a clue as to what soldiers experienced during the war. After our visit and presentation, students talked about it for weeks. Here’s what we did…

During the 1980s, on behalf of the Vietnam Veterans of America, Chapter 154, I visited the local high schools and spoke to the twelfth-grade history classes about my experiences in Vietnam. My presentation usually began with a photo slide show synchronized to Billy Joel’s song, “Goodnight Saigon.” To support this new educational venture, fellow chapter members joined me in contributing personal pictures from their tours which were then converted into slides for the projector’s carousel. Back then, most history books and classes taught very little about the war and how it affected mostly the “Baby Boomer” generation. This was just one way of getting the word out.

These teenage students were in awe during the presentation, staring at the screen – faces exhibiting a mix of emotions. There were no undertone comments or stirring in the room; the students sat transfixed by the images before them and remained extremely attentive during the one hour we were there.

When informed that the soldiers in the slide show were only a year older than most of them, the students all looked to one another in disbelief. Heads began shaking vigorously, and comments like, “no way, not this kid!” turned into a chorus. Video games had not yet been invented, so this was new territory for them.

Team ready to fly out to next mission – author is far right

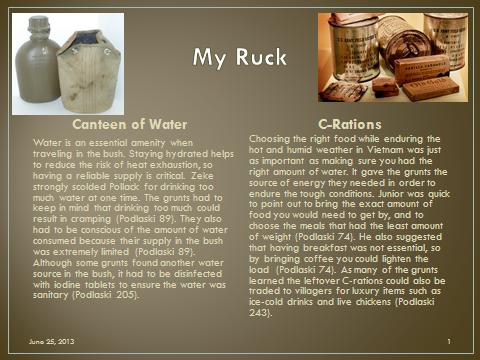

It was difficult for the students to fathom that food, water, clothing and personal hygiene products were not readily available in the boonies. For the infantry soldiers, meals consisted of canned c-rations; the menu and amount depended upon how much a soldier wanted to carry on his back over the next 3 – 4 days.

Doesn’t sound like much, but to press my point, I suggested that the next time they went to the supermarket, they should try collecting a dozen different meals in various-sized cans – taking enough to last 3 to 4 days. I offered up examples like cans of spaghetti or ravioli, tuna, veggies, soups, fruit, and meats; all should be placed in a single container and weighed to see what the total might be. Weight meant everything in the bush and having to carry any more than what was absolutely necessary was senseless to the grunts. The bare necessities alone that they carried were ammunition, grenades, trip flares, hand flares, claymore mines, poncho and liner, mortar round, a 100-round belt of machine gun ammo, weapon cleaning equipment, and personal stuff inside a waterproof ammo can. Add to it food, water, a steel helmet, a weapon, and more ammunition.

Speaking of water, let’s not forget that water is a necessity – so how much should they carry? Note: each quart of water weighs a little over two pounds. During the dry season, water sources were not readily available and each soldier had to carry a minimum of six one-quart canteens just to get him through to the next resupply – three or four days later. So, in rationing water, the ability to take care of personal hygiene needs such as washing faces, hands, hair or feet was a rare occurrence.

Filling canteens at the bottom of a B-52 bomb crater at the beginning of the monsoon season

During the monsoon season, it rained daily for months, and the water was plentiful. Bomb craters filled with water and became sources for both drinking water and bathing.

Canteens filled from these craters or streams had to be treated with iodine tablets to kill parasites and other “organisms and swimming stuff” before consuming – floaties and all. The water was often a murky color and had a slight odor, but after thirty minutes, it was supposedly safe for drinking. I’ve seen times when we ran out of drinking water the day before and came upon a pond or trickling stream to fill canteens. This was a critical time and extremely difficult for us to wait the allotted time before taking a drink. Those who couldn’t pay a price

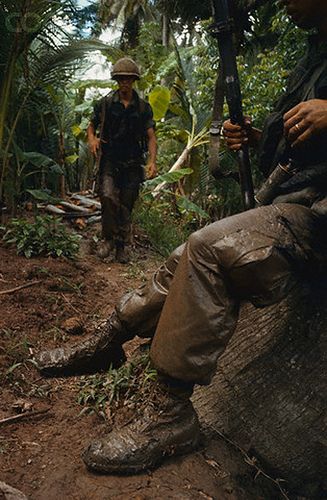

No time to bathe on patrol – troops simply cooling off

soon afterward – suffering intestinal inflammation and other maladies. Packets of Kool-Aide, lemonade, Tang and others helped to camouflage the metallic taste and “floaties” when iodine tablets were used.

Side note: We now know that the defoliant, Agent Orange, had leeched into the groundwater and streams, and rinsed from vegetation when we used to “catch” cold, refreshing rainwater as drops fell through the trees and surrounding foliage during the monsoon season. I don’t think Iodine tablets were strong enough to protect us though!!

The jungle fatigues worn by soldiers were lightweight and designed to dry quickly. However, during these humps through the jungle, fatigues were continuously soaked through with sweat, ripped by thorny vines, worn out by repeated crawling on the ground, and were never available in your size. Extra clothing, sometimes, came out on the resupply, but normally only enough for usually half of the men. As a result, only the worst cases got replacements. Everyone else had to wait their turn until the next resupply. It was not uncommon to wear the same fatigues for three weeks or more. By that time, most were a whitish color from evaporated sweat, stiff and brown from dried mud and sometimes blood, and every pair was ripped and torn throughout. The standing joke was that once removed, the trousers could stand on their own accord.

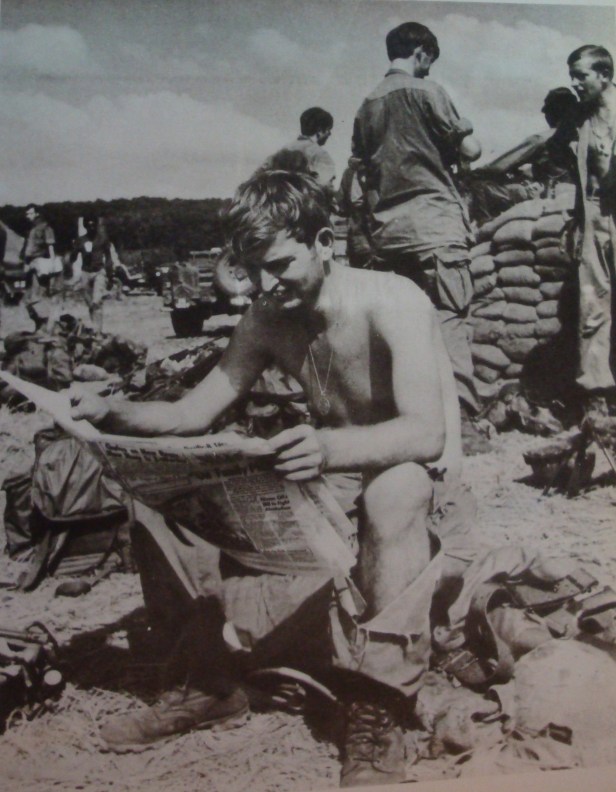

Troop awaiting his turn in the shower at the firebase after returning from a month-long mission

Grooming was another luxury that most of us didn’t have time for. We didn’t carry combs or hairbrushes, shaving equipment, soap, deodorant, toothpaste, and toothbrushes were used to clean our weapons and ammo. Smells carried in the jungle, enabling anyone to zero in on your position – even if they couldn’t see you.

Rice paddy water was full of feces etc. and unsafe to drink even with iodine – smells as bad as it looks

It was best to smell like the rotting jungle you lived in and offer up an identical scent. There was nobody to impress in the bush, and most if not all, could care less. At times, we were able to smell approaching enemy soldiers because of their diet of fish, rice and fermented sauce, and sometimes, the scent of burning weed when they smoked it.

Returning to the firebase after a month in the jungle was well received by everyone – except helicopter crews and those in the firebase; all giving us a wide berth and staying as far away from us as possible. The stench of returning warriors was unbearable to those greeting them at the gate. Many of us laughed because we didn’t notice anything different in the way we smelled, however, we were quick to note a clean and sterile, soapy smell as we entered the compound. It’s weird but true.

Community shower at the firebase – an exhilarating experience after returning from a mission

Food, water, and clothing were in abundance at the firebase – everyone could eat, drink and shower as much as they chose. This short visit only lasted three days. Then it was time to leave on another month-long jungle adventure.

These are the simple things in life that most people take for granted. Have you ever had to go a day or two without food or water because you didn’t pack enough? What about wearing the same clothing continuously for a couple of weeks or more? How about not bathing, washing or brushing your teeth for weeks at a time? It is difficult to imagine living like this, but to the young soldiers in the Vietnam jungles, this was a way of life. Unfortunately, these conditions contributed to a malady of skin diseases such as boils, ringworm, jungle rot, severe rashes, trench foot, and infected cuts and lesions. Nobody was spared. It was not pretty!

The school, later informed us that we had made quite an impression on the kids as they continued to talk about our visit. As a result, they asked us to return the following year but warned us that they were going to expand it to the entire high school student body. That was great news! I continued to use vacation days to address the schools and received a warm reception from the students during the next few years. My role soon evolved into the need for a “Speaker’s Bureau” in the chapter – adding members and duplicating the slides and projectors as more and more schools asked for us. I soon stepped down and let the “Cherries” carry the baton forward. The students of the era were a hungry bunch, soaking up every word and wanting to learn more and more about what we did in the war. In fact, I’d be willing to bet that many of the same students probably became soldiers themselves and participated in the Iraq invasion in the not-too-far future. NOTE: The VVA Chapter Speaker’s Bureau continues to this day and visits with dozens of schools every spring.

Below are three High School Student essays in part

On a personal note, I’ve learned that several high schools in the country were making my book, “Cherries”, mandatory reading in their history class. Teachers have sent me questions from students, copies of their completed projects (which I’ve shared on this website), and recently, introduced me to Skype so I could communicate with the class directly. I couldn’t be more proud.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

I didn’t plan on getting caught up in reading this post but it was so riveting and exciting that I couldn’t help myself. Every school in the country should offer a course like this. Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Have to say, I love these stories. I started in the Infantry business in 1984. Everything important I learned from Viet Nam vets. In 1984 at the Infantry Officers Basic course, they set up a training course for about a week. Us new lieutenants had to go through different stations clearing a trench, take out a bunker, react to fire, etc. Every station had a Viet Nam vet, E6 or E7 in charge of each station. There were maybe 10 stations, all basic Infantry tasks. Some of those NCO’s complained about it. It was not a demanding assignment for them – just make sure the Infantry tasks were done right and do an AAR with us afterward. But, as young LT’s, we loved it. It was great training and those vets always took it seriously. You all did great.

Tom

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, bro!

LikeLike

My sons teacher in I believe jmaybe 6th grade had asked them if any ones dad was in Nam and would they come talk to the class so I did and they to sat and listened to my talk and asked some good questions. I remember one girl asked me multiple times about how we got along with there being different races of people and I answered each one of her questions with we had each other’s backs and color had no meaning. Probably around 1991 and very little if anything was taught about Nam so I was appreciative that the teacher had asked me to speak to them. Therapeutic for me

LikeLiked by 1 person

Know this, so many troops had it worse than I and I salute them all. For me staying clean meant primarily two ways. I was an English speaking radioman with 1st ANGLICO working with ROK Marines in the Que Son Mtns. My primary duty was to communicate with Chopper Pilots, Medevacs and spotting gunfire. The routine was sitting on a hilltop with 12-15 other ROK’s and watch. Our water was delivered by Chinook in a net. The containers were 155 howitzer shell canisters. I got two to last two days but one never knew the weather or possible circumstances that would allow for the next delivery. So of course one would ration it. Hot, to say the least on the hilltop and without shade. Mostly all of natures shade had been blown away years earlier. There was scrub brush so to speak were folks could hide somewhat. The metal canisters served as an incubator for growth in the water. The water was never “clean” of microbes and algae upon arrival and got more putrid over the two days but it was sort of potable. Yes, added the iodine tabs but mostly boiled it using heat tabs before drinking. You remember the coffee/cocoa packs in the c-rats. By the second day the water in the second canister was actually starting to jell with brownish algae. Forgot to mention years later I calculated each canister held approximately two measly gallons, really not enough for the heat but it barely sufficed. Though I was medevacked twice to DaNang from drinking that water. FUO they called it in the malaria ward, fever undefined origin. Oh, oh I knew the origin for sure. Anyhow by day two if you were sure the resupply of water was on its way I’d pour the left over water into my “pot”, helmet and bath as best I could. After ten days my duty was done and another 1st ANGLICO Marine would replace me and I’d be dropped off in camp at Hoi An to take a real shower get fed real food with cold milk and white bread. They’d give me a couples days to decompress and visit China Beach and swim but dodging the floating Portuguese Man of War jellyfish. Then back to my home base outside of Dien Ban with the ROK’s. I and another ANGLICO guy, Nate Turner of Saginaw, Michigan had a shower stall built with a fifty gallon drum on top. The routine was fill the drum in the morn allowing the days sun to warm it and near dusk shower and wash the days filth/sweat off. You know, Navy shower style, get wet, shut off water, soap up and turn on water and rinse. How I stayed “clean”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

As a grunt with C company 1st bn 27th infantry 25th division I can relate to this message I believe that a vet can tell youngsters what they went through , but unless they actually have actually witnessed combat they still can’t know.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right on!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great read. Good depiction. Realistic. Only from a grunt. A2,503d,173d Abn,66/67

LikeLiked by 1 person

And that my friends is why I haven’t missed a day without a shower in over fifty years :).

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was the life a grunt for a year. Hoss 173rd

LikeLiked by 1 person

That was the life a grunt for a year. Hoss 173rd

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am glad the military learned from this war. I was sent to Iraq, almost twice. Glad we became technically advanced with our tactics and methods of survivability. I would of hated fighting in Iraq as we fought in Vietnam or any past war. So salute to those soldiers who died and survived for us to become great on the battle field. Salute

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nam I corp and north of Phu Bai to DMZ. On the money . Thank You

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was ten years old during the height it. Remember it well. Had friends in school that had brothers over there. One came home and one didn’t. God bless you and all the other men and woman that served.

LikeLiked by 1 person

My husband’s Dad and Uncle served there also many of other friends of ours , like most they didn’t talk much about it just now and than . Thanks to all who went and did their duty to keep us FREE!! Because you never got the Welcome HOME YOU DESERVED!!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

These are the stories that must be told. More importantly it has to be told by the soldiers who were there. They are the only ones who can be believed. I wish this was mandatory curriculum in all schools. Thank you for bringing out the realties of the Vietnam war. You are all heroes to millions of Americans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think more schools should have Vietnam vets give talks about their experiences during the Vietnam war😢

LikeLiked by 1 person

Vietnam = Ukraine

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are right on about the Rems staying away from us when we were in for a 3 day stand down. I remember cooking steaks and a mortar landing on the other side of our compound. Everyone from the rear was running like crazy for shelter, and we stayed there with our steaks. They all thought we were crazy and maybe we were, but nobody was getting my steak. Ha

Doyle, 1st 505th, 82nd Airborne 68/69. Keep up the good work and welcome home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have wondered many times through the years how soldiers eat and clean themselves while out fighting. Now I know and it makes me sick what our boys went through. I appreciate them even more than I did before and I’m so sorry that any of you had to go through what you did.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve always been interested in reading or hearing about Vietnam cuz my older brother served over there in 1968 during Tet. He doesn’t talk about it cuz,he says, it’s to painful.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I TO WENT TO HIGH SCHOOLS (2) FOR 8 YEARS TO TAKE OVER THE HISTORY CLASS. SHOW AND TELL WAS 300 ROUNDS OF M16 AMMO, DUMMY FRAGS, HELMET, PICTURES OF GRUNTS LIKE ME IN THE 1ST AIR CAV. A GOOD EXPIRIANCE FOR THEM AND ME.WISH I STILL DID

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very informative…So sad to see what our troops endured❗️

LikeLiked by 1 person

I think you hit the nail on it’s head, we spent about 3 months out at a time and the Maps didn’t like us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Auto correct, not Maps, MPs

LikeLiked by 1 person

Terrific article. Tells it exactly like it was. Thank you

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very correct letting their generation know what soldier’s do to make our country safer

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was an A-37 pilot at Bien Hoa. We had individual rooms in the hootch, a bar with plenty of beer, showers, and maids to wash our uniforms. Each room had a fridge and air conditioner. Here’ the kicker. One day I wound up chatting with some grunts from the other side of the base and I asked them how they withstood their “hikes” out in the jungle, you know, leeches, punji stakes, bullets flying, bad food, etc.? I told them I could never do what they were doing. They looked at me in amazement and said “we would NEVER do what you do!” What? They explained, “when we’re being shot at, there are 1000 of them and 1000 of us. When you show up they all stop shooting at us and they all shoot at you!” Crap, never thought of it that way, but I can say that there were days when I felt like I could step out of the jet and walk on the tracers, they were going by so thick. I was lucky to come back with my Purple Heart, I guess. It’s just your point of view.

LikeLiked by 2 people

196th Light Infantry 3/21 “C” Company. I served in Vietnam for the full year of 1969. My company took 43 KIA, 2 MIA, and 65 WIA. We had two Metal of Honor recipient, a few Silver Stars and many Bronze Stars for valor. I was a M60 machine gunner “The Pig”. When I arrived in country I weighted about 180 LBS. When I left country one year later I weighted in at 135LBS. Thank GOD for LRPs (Long Range Patrol Rations) or I would have come home at about 125 LBS. Besides carrying the M60 which weigh about 23 pounds I usually carried 200 rounds of linked ammo. I would carry more if I knew we were going to a hot LZ. As I gained more experience I would carry at least 4 grenades and sometimes a claymore mine. I learned to carry these weapons because in a large fire fight the NVA liked to get fight close so that our Artillery, Spook, etc. would not effect them. My backpack usually weighed in at 70 LBS with the M60, etc. I would also carry 2 quarts of water, one on my belt with my 45 pistol and the other on my rucksack. .

Our company would stay in the field for 90 days and then go on stand down in the rear for three days. We would fatten up a little and be sent to the field again. Some times in those 90 days we would go to an LZ and stand guard for two or three days. We were pretty much sleep deprived for those 90 days.

A few other things to mention:

*One or two towels were very important to carry

*The Monsoons rain were also cold. When they first came in you

would just take the cold and shiver.

*Guard duty every night for at least 2 hrs.

* Move almost every night to another night logger and dig in a new

fox hole. This constant moving would be exhausting. But had to be

done. You did not want to stay more than a night so that the NVA

would set up an ambush.

* Try to carry bug repellent in our helmet strap.

* Suicide was a problem. It all depended on the amount of sustained

action you were involved in.

There are many other things that could be added but these are just a few.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Brings back the horrible memories but everyone should read and know what it was like.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was great opens up your eyes to what these s soldiers had to deal with everyday I wad in during the Vietnam war but was station in the states I was in the infantry drove a personal carrier and was in the motor pool I can only say that God look out for me my heart brakes for what these soldiers had to go through .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the article and insight. My father was a marine at Iwo Jima and just recently passed. He left a brief diary for his children about his experiences. I was too young to serve in Vietnam. Thank you for your sacrifices.

LikeLiked by 1 person

His article is fantastic I have been trying to do this for the last few years I’ve been here in Las Vegas there is only one school that allowed us to go in and talk and at a five military man I was the only Marine combat veteran The rest were recruiters. And the way they spoke about the military I wouldn’t want to enlist.

I had to just glance over the article because there are too many triggers so I copied it and I will print it out and probably just read a little at a time but what I read of course I know is true because I was in country with the first battalion night Marines in 1967 we were known as the walking Dead

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very insightful account of the day to day of an ordinary soldier in Vietnam. Fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It has taken me fifty years to finally go through the letters my family saved. I wrote a book about it. I hope to have it published this year. My tour started on Hamburger Hill and ended at Firebase Ripcord. I used to be invited to talk about it but the teachers have moved on and the young people don’t know history.

Thanks for your service and welcome home brother.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this blog and ALL the great stories. I was on a M42 Duster at Con Thien and It was impossible to stay clean on that ole gun platform. Open turret with two 40mm bofors with a M41 tank chassis. Showers were few and I guess that’s why it made me feel so good when it was available .

At times we would be part of an mechanized infantry company and go out to pick up a LRRP team. Those guys would come out of that jungle grass and they were custy. I can’t even imagine how long between baths it must have been for them. My hat is off to all you grunts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

John, Thanks so much for writing this book. I was corpsman at Philly Nav. Hosp. at my first duty station and had the priviledge of working with the amputies coming from Nam. at times. I now have a realistic idea of what it was like actually being there and more importantly how they may have gotten their horrific injuries. Unfortunately our government treated them somewhat poorly and the people that spat at them upon their return owe them a huge apology. Lou

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lou. I’d be most appreciative if you would leave a review on Amazon.

On Sep 6, 2017 9:04 PM, “Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel” wrote:

>

LikeLike

Remember one day when we were supposed to get resupply and water. The brigade Col was pissed at us and sent nothing. We drank river water…no iodine. Pucking our guts our all night. 3rd Brigade Dau Tieng 4th ID 1967.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I hope that he rots in hell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That brigade Col should have been court marshalled.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Excellent. I was a cannon cocker so we usually had our mess, our showers (at least we had water), ammo, and other conveniences with us. We had vehicles to move our heavy stuff, and our 8-inch and 175mm’s were self propelled. Artillery raids of 3 to 5 days without the conveniences of a fire base, even if we the only ones on it, was the worse we ever experienced, so we can truly understand your story. I remember some of those boys coming into our perimeter and we talked to them from a distance offering food, water, showers, and even fresh clothing off our backs as necessary, and the gratitude they always showed for receiving it. They acted like it was a big deal, something they really weren’t entitled to, like they were supposed to be treated like some kind dirty thing. I still thank God to this day that I got into the artillery. Vivid memories have been coming back, some good, some not so. Thank for helping to educate our younger generations, they need to know the facts and the truth. There really are no safe places in war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You said a mouthful- “There really are no safe places in war.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

That article was dead on right from the start until the end. It really was hell. Lost a few buddies in the war. EVERY word 100% true Have health from lt. 69-70

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lets add the sleepless nights watching the enemy with one eye and sleeping with the other. You motivational story brought truth to war. Not those in a video machine. I appreciate you sharing you story. SF 5 Group.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The article is great but there is one mistake. A gallon of water weighs 7.2 pounds so a quart can’t weigh over 2 pounds. Well now, hold on a minute. He’s probably including the Canteen. I’ll be alright, Agent Orange at work. I look at

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well done American friend! I am an Australian infantry Vietnam Veteran, and like our American allies, we had to carry everything on our backs. My unit was First Battalion Royal Australian Regiment (1RAR) and everything you have pointed out is familiar. I was 19 years old when I was in action with the Aussie infantry in Vietnam. In 1RAR, we had to carry 4 quarts of water i.e. 4 full water bottles which were usually attached to our belts. Our back-packs were simply dumped on the ground if we had “contact” with the enemy forces. Contact was Aussie army speak for closing with and killing the enemy. You can read more about Aussie infantry operations in Vietnam 1968 – 1969 in my book entitled “Full Circle for Mick” and available from http://www.amazon.com or http://www.mickkramer.com.au Kind regards Michael Kramer

LikeLiked by 2 people

I served in Vietnam with the 3rd Marine Division from 12/67 to 08/69. I was in artillery on 155’s towed. Like you we would spend extended periods of time in the field supporting the 105 batteries and the grunts. The only time we had the chance to shower was when it rained, and then we would put back on the same dirty clothes. We would have all kinds of grease on them from working on the guns in between fire missions . C-rations every day. When we came out of the field we would take showers and come out thinking we were clean, until we got outside and we would see these red blotches all over us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was also with the 3rd Marine Division, K-4-12 155 howitzers both self propelled and towed. My Vietnam days were summer of 1965 to September of 1966. Everyone remembers the water, which for us was treated with bleach. C rats for food and I can’t remember taking a shower. I had chunks of my feet falling off due being soaked all the time. My longest time out was 40 days. I can’t imagine being out more than double that as some have stated. I nearly lost my mind at 40 days. I recall going to DaNang Air Base when it was time to go back to the world, and getting to enjoy a real city before a C-130 ride home. I’m livin large now since the VA has detemined to give me an agent orange – Diabetes disability. I’m almost 76 years old.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I enjoyed your story and thanks for sharing it. We spent just over 100 days in the field one time. When we came into the firebase for a short time we were all getting showers when one of the guys who came in while we were in the field looked over at me and said I didn’t know you had blond hair. The red in the soil made everything else red including us. Leaches, rats and other creatures were also a problem.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Right on the mark. Reading your story

Was like me remembering my time in the bush

Very informative

LikeLiked by 1 person

100% A curate…still remember the smells of us and the “Sweet, Pungent, odor of the NVA…We could smell them from low level Helicopter recon over an area where they were or recently left…!

I will never get that smell out of my mind…!

Great Report…and of course very authentic and real…!

Michael Ronsiek

7/17th Air CAV

69 and 70

Welcome

Home Brothers..!

LikeLiked by 1 person

EXCELLENT !! More young people need to see this, thank you from this Grunt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank You!, for keeping our history alive for everyone to read and enjoy. Veterans are what this country is made of. We are ALL Brothers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a Vn.Vet gr8 history lesson

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a Vn.Vet gr8 history lesson

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was a US Army grunt in the Nam (69/70),, Your article is spot on,, When we came in to the rear, all the rear personnel (forgot what we called them) they would stay away and leave us alone,,first thing we sought out was a shower and clean clothes, and dry place to sleep. Unbelievable nasty conditions,, and your right about the weight, I was the CO’s RTO,, so I humped the radio,extra handset, squak box, extra battery,and long antenna. At least I didn’t carry any ammo for the pig,, I had enough on my back.. Welcome Home great article ..

LikeLiked by 1 person

RTO myself. now I have bad back bad shoulders and hemorrhoids. Hard to explain to my wife what it really was like. since she is the only one who really cared. Rock on my friends, We Understand and that’s really all that matters..

LikeLiked by 2 people

Spent two tours in Vietnam and on my return to the US the welcome was at the least unsettling.

My final tour was in Iraq 2008 and the welcome home was much better. Welcome home my friend.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Outstanding !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person