Thirteen years after the North Vietnamese government’s Resolution 15, in January 1959, set in motion the armed struggle to conquer South Vietnam, North Vietnamese Army (NVA) General Vo Nguyen Giap believed he had found the elusive ‘center of gravity’ he had been searching for. Four years earlier, with the Tet Offensive of 1968, he had thought it was the relationship between the South Vietnamese people and their government. But the ‘Great General Uprising’ he had counted on never materialized, and his Viet Cong (VC) guerrilla auxiliaries were annihilated in the process.

But this time it would be different. Since that debacle, the United States had begun a process of what it called ‘Vietnamization’ — i.e., turning the war over to a rearmed and equipped South Vietnamese military while the Americans gradually withdrew. Beginning in 1969, U.S. Army and Marine combat divisions began leaving Vietnam. By 1970, both Marine divisions had departed, and by 1972 American in-country strength had fallen from a peak of 550,000 to some 75,000. The only U.S. Army ground combat units left in Vietnam were the 196th Light Infantry Brigade and the 3rd Brigade of the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile). U.S. Air Force and naval units had been drawn down as well.

It appeared that a classic center of gravity had been created — the relationship between South Vietnam and its American ally. Not only had the majority of U.S. military forces been withdrawn but American congressional and public opinion had shifted dramatically against the war, and the chance of U.S. reintervention appeared to be nil. All that remained was for the NVA to administer the coup de grace.

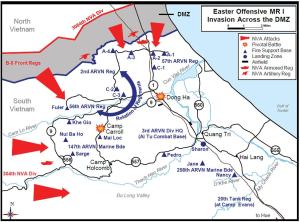

And that’s what their Operation Nguyen Hue was designed to do. Better known as the ‘Eastertide Offensive,’ it dropped all pretense of guerrilla war. Instead, it was a three-pronged multidivision NVA cross-border invasion, well supported by tanks and heavy artillery. General Giap committed six NVA divisions to the attack in I Corps in the northern portion of South Vietnam. Another three NVA divisions were ordered to strike in II Corps in central South Vietnam, and yet another NVA/VC three-division force would attack in III Corps north of Saigon.

By the second day of Nguyen Hue, the situation along the DMZ was critical. The general confusion and the tendency of the ARVN field commanders to downplay their bad fortune led both South Vietnamese and U.S. senior military officials in Saigon initially to dismiss the invasion across the DMZ as a diversionary attack and to believe that the real thrust of the anticipated North Vietnamese offensive would occur in the Central Highlands farther south.

The lack of South Vietnamese aggressiveness up to this point produced a lull on the battlefield, allowing the NVA to reorganize their forces and replace the heavy losses they had sustained from U.S. airstrikes. The NVA took advantage of the bad flying weather to strike when tactical airpower would be least effective. Following an artillery and mortar barrage, the North Vietnamese took Dong Ha on April 28, forcing the South Vietnamese defenders to retreat into the Quang Tri citadel. There, the ARVN continued their defensive actions while airmen took advantage of clearing skies to mount concentrated airstrikes — as many as 200 sorties per day.

The next day, the equivalent of four NVA divisions mounted their final advance on Quang Tri. In the face of massive artillery attacks (over 4,500 rounds fell on the city in one day) and tank-supported infantry attacks, the South Vietnamese defenders broke and ran, leaving substantial quantities of weapons and supplies intact. The green 56th Regiment surrendered to the Communists, forcing its two American advisers to make their escape by helicopter.

While allied tactical air pounded the NVA positions to great effect, the South Vietnamese forces, led by a proven commander, General Ngo Quang Troung, reorganized around Hue and launched several successful spoiling attacks against Communist forces poised to move on the old capital city. The North Vietnamese did make several drives on Hue in later May, the most notable taking place on May 29, but it failed when the South Vietnamese, though outnumbered, pushed the North Vietnamese back across the Perfume River. Unable to take Hue, and reeling under the destructive weight of U.S. B-52 strikes, the North Vietnamese withdrew from their position in northern South Vietnam. On June 28, Troung’s forces advanced north and fought to take Quang Tri.

Meanwhile, the NVA had launched the second effort of their battle plan in II Corps in the Central Highlands. The NVA 320th Division, supported by tanks and anti-aircraft weapons, swept across the Laotian border and advanced on the city of Kontum, badly mauling the 22nd ARVN Division in the process. The 22nd Division was split between the Highlands and the coast, where it still had area security missions and was more or less chopped up in detail (i.e., defeated one unit at a time).

The first major drive on Kontum itself occurred on the morning of May 14. Battalion-sized units of NVA soldiers supported by two columns of tanks attacked from the north and northwest. South Vietnamese defenders, using hand-held anti-tank weapons and supported by fighter-bombers, were able to deal with the tanks and held their ground. Similar attacks were launched and subsequently broken up by the Kontum defenders and by U.S. and South Vietnamese air power over the next several days. Of particular help against the North Vietnamese tanks was the introduction of the TOW (tube-launched, optically tracked, wire-guided) anti-tank missile. These missiles, launched from U.S. Army helicopters and guided to their targets by the pilots, gave the allies a great advantage by being able to pick off the NVA tanks as they moved in to attack. Of the first 101 firings, 89 scored direct hits on enemy tanks and trucks. Through June 12, the U.S. Army claimed 26 tank kills by the helicopter-launched missiles, including at least 11 T-54s in the Kontum area.

The third prong of the NVA attack began on April 2, as the enemy 5th Division, composed of both Viet Cong and NVA units, rolled into northern Tay Ninh province in III Corps and attacked the fire support base at Lac Long. Within two days the Communists had effective control of key positions in the province and were able to direct their attention to their main objectives, the towns and airfields in Loc Ninh, An Loc and Quan Loi, along with positions astride Highway 13, the main highway connecting the region with Saigon. As elsewhere, the Communists? main objectives were to establish a regional government and to better position themselves for subsequent ‘peace’ talks. The city of Loc Ninh, located close to the Cambodian border, fell within a couple of days and subsequently became the capital of the Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam (PRGSVN), a distinction it held until it was disbanded by the North Vietnamese after the war.

Supported by U.S. B-52 airstrikes and U.S. and South Vietnamese tactical airstrikes, the defenders at An Loc were able to hold out as American air power effectively broke up the NVA troop concentrations around the city. A captured letter, handwritten by the political commissar of the NVA’s 9th Division to his higher headquarters, reported that the allied tactical air and B-52 strikes had been unbelievably devastating. Finally, the Communist forces lifted their siege on July 11 and withdrew to their base areas in Cambodia.

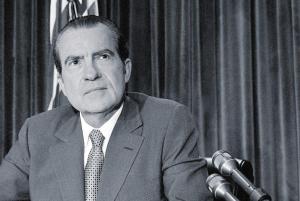

For the United States, and especially for President Richard Nixon, the invasion could not have come at a worse time. Enjoying foreign policy successes abroad but a shaky economy at home, the president would just as soon not have had to deal with the Vietnam issue. Politically, as General Giap had foreseen, it was impossible to reintroduce sufficient U.S. combat troops to stem the NVA drive. The major U.S. contribution to the South Vietnamese effort, besides political and materiel support, would be fire support in the form of naval gunfire from U.S ships off the Vietnamese coast and, most important, airpower.

The diminishing U.S. role in the Vietnam War during this period of Vietnamization had left U.S. air assets at a fraction of their past strength in Southeast Asia. Before the offensive started, three squadrons of F-4 fighter-bombers and a single squadron of A-37 attack aircraft made up the U.S. Air Force’s presence in Vietnam, a total of 76 planes. United States Navy and Marine aviation assets located in-country and off the coast of Vietnam augmented this total.

With his reputation and his policy of Vietnamization at stake, Nixon implemented a massive buildup of airpower in Southeast Asia and a broadening of the eligible targets. On April 6, U.S. fighter-bombers raided military targets 100 kilometers north of the demilitarized zone. As the available air assets made their strikes both in support of the beleaguered ARVN units and against targets in North Vietnam, squadrons of U.S. military aircraft redeployed from their bases in Japan, Korea, the Philippines and the U.S. mainland. Simultaneously, more aircraft carriers steamed toward Vietnam to join the two already on station there, until by late spring there were six aircraft carriers, each with approximately 90 craft, operating off the coast.

U.S. tactical airpower was stemming the tide of the Communist invasion, but it was not turning it back. While the ARVN ground forces were holding, they were in no shape to drive the NVA from South Vietnam. If the United States was going to stop North Vietnam, it would have to greatly increase its pressure. Instead of concentrating on the tactical situation on the battlefield, the United States would have to hit the North on a strategic scale.

I

I

Cutting rail and communication lines and interdicting land-based supplies was accomplished to much greater effect than during attempts earlier in the war. This was due mainly to the introduction of precision-guided munitions, commonly referred to in the press as smart bombs.’ These weapons, dropped from aircraft and then guided to their target by the pilot using either television or lasers, allowed a pinpoint accuracy never before enjoyed on the battlefield. Key targets previously restricted because of their proximity to foreign borders or civilian areas could now be attacked.

The Soviet-built Lang Chi hydroelectric plant, located 63 miles northwest of Hanoi on the Red River, was capable of supplying up to 75 percent of Hanoi’s electricity, but breaching its dam could drown as many as 23,000 civilians. On June 10, F-4 laser bombers put 12 Mk .84s through the 50-by-100-foot roof of the main building, destroying the plant’s turbines and generators without putting a crack in the dam.

Stiff South Vietnamese defenses at An Loc and Kontum, a spirited counterattack around Quang Tri, and the crippling effect of U.S. airpower brought the offensive to a standstill by early summer. The North Vietnamese abandoned their sieges of Kontum and An Loc by mid-June. In September, South Vietnamese forces were able to recapture the remnants of the city of Quang Tri from a token Communist force. In the end, the North Vietnamese forces were able to hold on to only two district towns, Loc Ninh and Dong Ha.

The invasion of 1972 saw the first enemy use of massed armor coordinated with infantry and artillery in a fashion that the American generals, trained in European-style mechanized warfare, would be quite familiar with. In fact, the overt invasion by the North proved to be the opportunity that American military and planners had long dreamed of: to lure the elusive Communists into the open in a conventional, setpiece battle. Only in this type of conflict could the United States’ huge advantage in firepower and mobility be effectively exploited.

The North Vietnamese had a big battlefield edge over the South because of their artillery. The North Vietnamese deployed three regiments of artillery totaling several hundred guns to go along with the equivalent of two tank regiments and 17 infantry regiments. The Soviet-made 130mm cannon could do much damage. It had an effective standoff range of 27,500 meters and could outgun practically every artillery piece in both the U.S. and U.S.-equipped South Vietnamese armies.

In terms of equipment, the South Vietnamese were equivalent, if in some areas not superior, to their brothers in the North. The major problem that ARVN suffered from was leadership, especially at the higher levels. Too often during the battle, as well as throughout the war, the battalion, regimental and divisional commanders suffered from indecision at crucial moments. The field commanders also exhibited a lack of aggressiveness and initiative on the battlefield, preferring to let U.S. and South Vietnamese air power take on enemy forces rather than engage them themselves.

The Vietnamese extreme concern with saving face’ also contributed to their unwillingness to take chances or to take personal responsibility for their actions. This belief probably contributed to the early successes of the North Vietnamese since the ARVN leadership was reluctant to report the reality of the situation.

This poor leadership translated directly into poor morale among the front-line soldiers who would have to fight and die if the South Vietnamese forces would turn back the invaders. Despite that disadvantage, however, in the end the ARVN, encouraged by the presence of U.S. air support, held.

As the offensive petered out, the North Vietnam government and military had to take stock of what their effort had won them and what it had cost them. Analysts estimate that between 50,000 and 75,000 NVA died as a result of Operation Nguyen Hue. Many more were wounded, and massive materiel losses included more than 700 tanks. The ARVN suffered~10,000 killed, 33,000 wounded, and 3,500 missing.

This article was written by James Moore and originally published in the February 1992 issue of Vietnam Magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Vietnam Magazine today!

You say that the USMC was completely out of ‘Nam by the end of 1970. My late husband was USMC (ChuLai) and finally was discharged in Feb ’71.

I don’t know why, probably waiting on discharge papers and all that…but he said it took about a month to finally make it home. So, going by what you say here, he was probably on one of the last planes to leave.

I do love reading your stories; they bring home to me so much of what he used to talk about…even years later. He finally passed away from Agent Orange complications in 2014.

SEMPER FIDELIS ❤️️🇺🇸💙 …

LikeLike

So sorry for your loss. Thank you for you r compliment.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Lose! Never. We had to fight the NVA/VC as well as our politicians and most of the American press as well as the college scumbags that had the “out”. Lost…Carter pardoned the draft dodgers who were welcomed home with open arms! We got shit.

LikeLike

Excellent rendition on how effective combined US forces could be in bolstering the ARVN. And it pushes aside the mistaken belief (I hold…) that we lost in Vietnam. Rather, we were constrained and further lost control by putting local people in charge who, for one reason or another, did not hold the line, so to speak.

LikeLike

Not all Vietnam veterans think we lost, instead we were constrained by politicians – even the NVA colonel who accepted the S. Vietnamese surrender agrees:

https://smallwarsjournal.com/index.php/jrnl/art/historically-and-factually-accurate

LikeLike

Like, I really should have proof read those words in parenthesis, they should read…I DON’T hold….my apologies.

LikeLike

Great story. Unfortunately the leadership of the ARVN was not good and the higher ups were there for their benefit. In other words, give me money!! Then when the south fell in 1975, those major officers in the ARVN fled the country and had their money stashed off shore and came to the US and and lived the good life.

LikeLike

The 525th MI Group was still active in I Corps and elsewhere.

The NVA assault was staggered: I Corps, then III Corps, then II Corps and Giap was not running the show, either.

Initial NVA assault into Quang Tri and Thua Thien Provinces: 3 infantry divisions; 3 separate infantry regiments; 2 composite AAA divisions (367th and 377th); 9 field artillery regiments; 2 armored regiments; 2 engineer regiments (including the 126 Naval Sapper); and 16 sapper, signal, and transport battalions were present at the onset.

Ultimately in I Corps, three more infantry divisions, plus the last regiment for a newly created division in southern I Corps were sent into I Corps – the 2nd NVA Infantry Division was sent to fight at Kontum.

My forthcoming book: Break in the Chain: Intelligence Ignored will be published this summer.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing the article by James Moore regarding the Vietnam War. I recall how the Vietnam War profoundly impacted me as a young adult and tragically caused division in the United States.

LikeLiked by 1 person