If you want to listen to this article on Spotify, then click on this link: https://open.spotify.com/episode/5bEOY6OtAI1cnJdnfDypSe

My guest today relates to what life was like for teenagers living on Army bases while their father’s served in Vietnam. They were all raised to believe that country came first, and all had an obligation to serve if called. Many followed in their father’s footsteps and ended up in Vietnam themselves.

By Bob Baker

As an Army brat, we lived in many places. Patrick AFB FL, Huntsville, AL, Kaiserslautern FRG (the Berlin Wall went up on my birthday and we were sent home on the SS.General Patch), Albuquerque, NM, Aberdeen Proving Grounds, MD, and Aurora, CO.

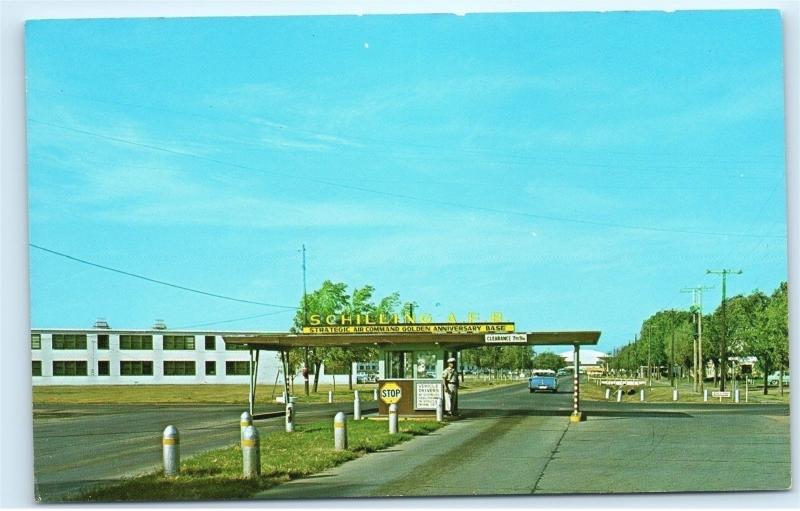

My last two years of high school were spent dodging tornadoes in Salina, Kansas. The old Strategic Air Command base had a long main airstrip that B-47s used. Shilling Air Force Base had become a city airport, with most of the surrounding buildings and housing area transferred to the Army. This became a sub-post of Fort Riley with the post housing called Shilling Manor, which became a “Home of the Waiting Wives.” Servicemen of all the U.S. Armed Services (officer and enlisted) bound for Vietnam could drop off their families at this post until their tour was completed.

Somewhat remote from the small city, there were only two roads into the post. There was a movie theater, small commissary, and small dispensary that served the community. Buses took high school students to a single high school. Kansas Wesleyan University is located in the city.

It was a challenge to keep teenagers occupied and out of trouble, but it seemed to work – everyone in the same boat, as it were. Parents, being parents, moms would also look after all the kids – remember, it was a different time when kids were brought up to respect their parents and all adults (and they enforced it as necessary).

I remember Barney Fife, named after the television show character. A likable deputy sheriff who patrolled the housing area, he was easy to outfox because he was predictable in his patrolling.

Though families were safe, not everyone could escape “The Visit” that brought an officer and a chaplain to the door – it could be a very sad place. A nearby Army family and the family of a U.S. Navy pilot come immediately to mind when I think of this, especially every Memorial Day. All of Schilling would know within an hour when this happened and all would do what they could for the family.

There was no choice but to learn to drive a car before my father left for Vietnam. I took on volunteering to coach football, baseball, and basketball for the younger kids of the post. The Army must have seen some merit in employing teenagers, as they paid us after the first year. During summer, there was grass to be cut, floors to be washed, waxed, and buffed and taking shifts to manage the pool room – virtually every teenager learned to shoot pool. Jukebox dances every other week also helped the time to pass. All of these things helped keep the teenagers busy and $1.60 an hour helped greatly.

As I neared high school graduation, I remember former students of some of the teachers returning from Vietnam speaking to the class. This usually included displaying and talking about their wounds, if they had any. For teenagers from the post, the impact was deeper than they would publicly admit. The realization that their fathers might return with such a wound or worse had an almost unspoken effect on us all.

Most of us expected to be in one of the armed services. Almost all of us knew that college would have to wait. We were all raised to believe that country came first and we had an obligation to serve, if called – the Jane Fonda and rich college kids burning their draft cards were not really America. Unfortunately, the TV branded everyone of a certain age as being a hippie and anti-war, but it wasn’t so.

My youngest sister was born in a civilian hospital in Salina. Her twin sister didn’t survive but an hour. As the oldest of seven, I had to inform my mother (and my siblings) about the twin and make arrangements to have my father return from Vietnam. My father was able to stay at Schilling afterward for a couple of years until he again returned to Vietnam in 1970.

A notice to get a physical from my draft board hastened my Army enlistment. My dad and I missed being there at the same time in 1971 by one month. Unlike most, my father and I could talk about Vietnam and the things we saw and felt and made our relationship stronger.

Thank you, brother – a great remembrance.

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

I could relate I was a army brat. Who was raised on an army base ft Eutis VA.from1952 to 1961 .when my father retired.I joined I n DEC 1964 I left for basic trading ft Mc Cl . Ala. I got lucky. An Jan I left after basic an was station at ft. D ix N.J.I was taught that as said before we were rasied to believe Fight for our country an an our freedom. An Country then Family. If kids today had been raised as we were .no electrons. Simply .like going to dances

supervised. An Drive inn movies. An that our President. Were very well trained. Military trained. An knew how to run a country. An We had. Freedom .people had. Fought here for. Blacks to have. Rights an freedom an Women to be free to vote an run companies. That’s Why We Fought in Vietnam. For them to be free. But we chose to bring them here an give them Money to buy busniss an money to buy new homes an autos. I never understood Why we .let our people born here. But could not get help for money food autos just look at us now we have a high homeless rate here.Our Vets Are Number One in homeless. Whole family with children standing .on street coners asking for work .food. American. Is not the home of the Free any more. But I as a Vietnam vet. Am starting a company to build affordable. Gated homes for our Vets. A very humble Vets. Who gave still giving. I will be looking for partners all vets .The Company will be owned by all vets. A very. Grateful Vet Medic Bernice Draper .

LikeLiked by 2 people

Some of what was posted, I could relate too. I was raised in the military, army/air force. My dad was 1st Cav, fought in the Philippines but switched to the air force when it was created in 1947. We lived in base housing on different bases. Neighbors looked out for each other and kids. Out of control kids would be dealt with by the neighbors. Never tell your folks as double jeopardy did not exist for us. Do the crime, take our punishment and keep your mouth shut and hope that dad and mom never heard what happened. I joined the service right after graduating, 1962, so Vietnam had not really started with families being notified of a member being KIA. My kids were raised in the service and made lots of friends. Some friendships continued as people being transferred would be on the same base or close by. A service dependent gets I think a great education of the country and interaction with other people. Some of my kids looked at it that way. Some were to young to remember much before I retired in 1986.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Interesting article. The author’s dismissal of those protesting the war reflected the fact that he was living in the military bubble and had little idea of what was going on in society at large. Must have been difficult growing up on bases during the war.

LikeLiked by 2 people

I thought that was a good perspective. However when the 199th Bde departed for Vietnam from Ft Benning all their families on post ended up departing for their home towns. The Army had little space for the dependents and sent them packing. I felt that was a pretty heartless thing to do.

LikeLiked by 2 people

it certainly was, enough of heartache with your dad leaving for Vietnam then you had to leave your quarters because you couldn’t stay. I’m an Army Brat and my dad left for Korea and we moved to Ft Lewis. Dad didn’t come to Ft Lewis they sent him to Japan and we followed. When my dad left for Vietnam. I was 23 with two pre school boys. We left to go to Va to see my Dad off. 8 months after dad left for Vietnam my 19 yr old brother arrived in Vietnam. Dad was a Combat Engineer and my brother was 173 rd Airborne. It’s Anna Deal Brehm hard when your dad was there and your younger brother

LikeLike

Patrick AFB is now The Space Force base

Sent from my iPhone

>

LikeLiked by 2 people

I was in elementary school there, as my dad worked at Cape Canaveral. Little known fact is the Army ran it at first.

One of my sisters’ Air Force husband was assigned to Patrick. They lived a few blocks away from where we lived some 20 years or so before.

LikeLiked by 1 person