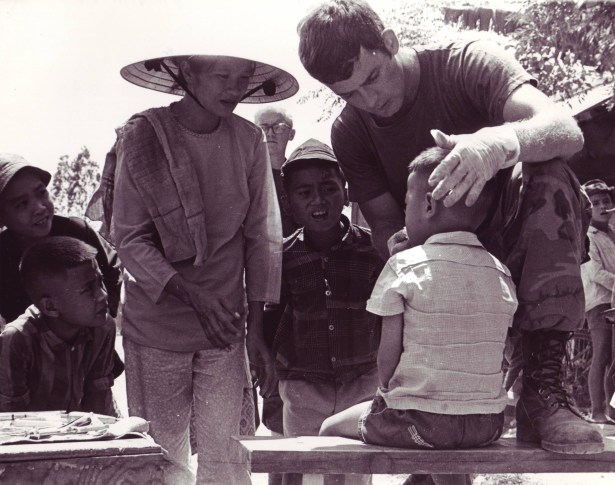

As Christmas approaches, my friend, Jim Van Straten, a former officer in the Medical Corps during the Vietnam War, sent me an excerpt from his book titled, A Different Face of War for publication on this website. It truly does describe an “unforgettable” Christmas Eve.

After about ninety minutes at the bar, three friends and I decided it was time for dinner. We went downstairs to the dining room and enjoyed a very nice meal. The Vietnamese chef had added special things to the menu for the occasion and we all savored the tasty and nicely served dinner.

But soon the dinner ended, and then what was I to do? Going back to the loneliness of my room on Christmas Eve sounded dismal, so along with the others, I headed back to the bar. The mood had changed, now becoming melancholy. There were more “Bah, humbugs” than there were Merry Christmases. The Christmas carols seemed to add to the loneliness. “I’ll be Home for Christmas.” Bah, humbug! “Chestnuts Roasting on an Open Fire.” Who cares?

Meanwhile, the mixed drinks and the beer continued to flow. Soon the heads and shoulders of those sitting at the bar began to sag, signaling the loneliness of the moment. A few tried to play the game of dice called horse, usually a spirited game, but even that seemed dispirited and out of place. The clacking of the dice, as they were rolled onto the bar, and Bing Crosby crooning “White Christmas,” was about the only sounds in the barroom. The conversation became less and less. The spirit of the holiday was being held captive by the loneliness caused by separation from family and friends on Christmas Eve.

Soon my fellow officers started drifting away, returning to the loneliness of their rooms. I soon followed. I drove back to my billet, arriving at about 2230, and immediately got ready for bed. Sometime after 2330 hours a pounding on my door awakened me from a deep, alcohol-induced sleep. Groggily, I went to the door and was told to go to I Corps HQ immediately. There had been a plane crash and maybe I could help.

The plane had crashed into the small village of Binh Thai in Hoa Vang District, about a mile south of the Da Nang Air Base. It had skidded through the village for about 400 yards. The fuselage and wings of the plane had demolished all the homes in its path. The crew members of the plane all died on contact, and the devastation in the village was unbelievable. I recognized one of the Vietnamese medical officials at the site. He spoke passable English. He and I moved through the destroyed village, doing what we could to ensure that the American and Vietnamese medical responders were working in a somewhat coordinated manner. Most of the responders were American servicemen. There seemed to be scores of U.S. Marines digging through the rubble, attempting to locate injured survivors and get them transported to Da Nang hospitals as quickly as possible. The Marines also had the sad task of extracting the bodies of the dead. Many children were among the injured and dead. Several were decapitated or dismembered and many were seriously burned. It was heart-rending for all of us who were trying to help out at the site of the disaster.

Those of us trying to provide assistance made one grave error. Despite the protestation of the Vietnamese families of the victims, we insisted on evacuating the dead to an established morgue in Da Nang, several miles away from the village. Initially, a temporary morgue had been established in the destroyed village itself by simply roping off an area and trying to shield it from the sight of onlookers, but as the number of corpses grew a decision was made to take the corpses to established morgues in Da Nang. This proved to be culturally insensitive, as the Vietnamese looked upon a morgue very unfavorably. They much preferred retaining the bodies of deceased loved ones in their own village, performing their own preparation of the remains for burial, and following their own burial customs. Later we regretted this decision, but at the time it seemed proper. We attributed the protestation of the victim’s families to the anguish of the moment. We were wrong. Eventually, an American military directive was published addressing this lesson learned. After conferring with many of my Vietnamese friends and colleagues, I provided input for the writing of this directive.

I returned to my room at about 1100 hours on Christmas morning, very dirty and very tired and too late to attend church services. I cannot say how many times during the past forty-nine years my thoughts have gone back to the people of that small village and the tragedy that occurred there on Christmas Eve 1966.

++++

Jim Van Straten was a U.S. Army major in the Medical Service Corps in Vietnam at the time of the described incident in December 1966. He served a full 30-year career, retiring in the rank of colonel (0-6). Now lives in Windcrest, Texas, which is a suburban city on the edge of San Antonio. A Different Face of War is Jim’s first published book. Here is the direct Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/Different-Face-War-Memories-Biography-ebook/dp/B01944VY3E

Jim Van Straten was a U.S. Army major in the Medical Service Corps in Vietnam at the time of the described incident in December 1966. He served a full 30-year career, retiring in the rank of colonel (0-6). Now lives in Windcrest, Texas, which is a suburban city on the edge of San Antonio. A Different Face of War is Jim’s first published book. Here is the direct Amazon link: https://www.amazon.com/Different-Face-War-Memories-Biography-ebook/dp/B01944VY3E

My heart is breaking. My fiancee was the navigator on that plane. Lloyd James Moore. Thank you.

LikeLike

I was there at Danang Christmas Eve working security with the 366

I can’t explain how the sky lite up,

We helped set up security but I didn’t have to help with the bodies, their count 123 our men on site a lot more.Every Christmas Eve I say a prayer for the lost lives I was 19 on the 22 of December .

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Colonel for your service to your country. I loved the book and thank you so much for writing it. Should be required reading for all schools. Also thanks to your son Steve for his service. I served in the Marines and in 1968 got orders for West Pac Ground forces DaNang but for the grace of God, my orders were changed while on a stop in Okinawa and I stayed there for 14 months.

LikeLike

What did those poor villagers get? An apology?

LikeLike

I experienced a similarly tragic Christmas Eve in Vietnam. You don’t forget.

LikeLike

I spent Christmas 1967 at Con Thien on the strip. Was a normal Christmas Eve and day. No different than the days before or after. Rain, mud , cold and wet. Spent the night in a Die Marker bunker. Our living quarters and dining areas were starkly different and it’s hard to understand what you had to complain about but I think maybe after finishing your artical I would just as soon have my memory of Christmas than yours. Just saying.

LikeLike

Excellent recount, one of th better ones, guess I can remember these and othe incidents, similar !

LikeLike

The whole time, the American Forces was in Viet Nam. Was a worthless or useless waste of everything. Especially all the people, who were killed there. I was in the Nam, from early in May 1970 until Early May 1971. First based in Long Bin, near Saigon. Then we merged with 572d Trans Co. Took all Trucks & Equipment to Port Of Saigon. Then we 2 Companies boarded C-147z and flew North. Made (1) fuel stop in Cam Rhan Bay. Then we continued via air to a landing zone, near Quang Tri. From the LZ, we were carried to an open space . And there we for, 3/4 days in the open. we did dig Bunkers ETC for protection. Then as soon as our Trucks and equipment arrived at the Port near there. We were transported by vehicles, to the Port. Obtained all Trucks & equipment then returned to our new, location. Then we assumed, hauling AMMO and supplies to outlying Bases. This was all near, the (DMZ). My tour was over, I flew from that God Forsaken Country. That was, all unwanted.

LikeLike

Christmas Eve 1968, my company and I were on ambush out at the edge of the Michelin rubber plantation, posted outside on OP. And later that nite on my stomach when we opened up on some VC. When the sun rose we found out we hadn’t killed all the enemy and that’s when I got it in the hand and the fella next to me got hit in the leg. I’ve been told three adults and some children were killed in our ambush.

LikeLike

But Curtis, you couldn’t possibly have been ambushed on Christmas Eve – there was a holiday ceasefire. Our leaders told us so . Guess, as always, the VC/NVA didn’t get the message.

LikeLike

Jim, thanks for sharing your Christmas story, even though it was a tragic one. You mentioned early in your story the condition that effected all of us, especially during the holidays – loneliness. I’ve been asked several times why we (I) drank so much while I was in Nam and my answer is always – loneliness. Thank you again for sharing your story. Thank you for your service to our country. Merry Christmas. And welcome home.

Les

LikeLike