A Dust Off helicopter landing with a load of wounded at the LZ Hawk Hill aid station pad in early 1970. (Photo by Robert Robeson.)

The attached article by Robert B. Robeson was recently published in the November 2019 issue of Military Magazine.

“They were going to look at war, the red animal–war, the blood-swollen god.”–Stephen Crane, The Red Badge of Courage (1895),

I’ve always believed that there are lessons to be learned from some of humanity’s worst moments. War, heads my own personal list. Armed conflict causes its participants to reflect on the jagged landscape of the human heart where trouble, fear, pain, bloodshed, and death are a dominate part of soldiers’ daily existence. It’s a world of creative cruelty, like having ISIS show up at an infidel’s birthday party with butcher knives. Sometimes surviving in such an environment is often as easy as attempting to perform a disappearing magic trick in front of a firing squad.

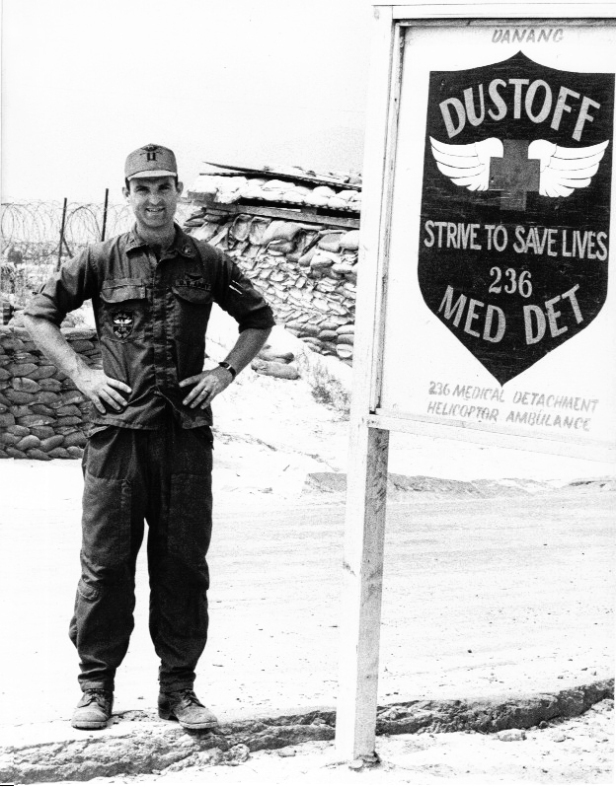

From July 1969-July 1970, I was a U.S. Army captain and medical evacuation pilot in Da Nang, South Vietnam, during the Vietnam War, assigned to the 236th Medical Detachment (Helicopter Ambulance). Life in this aviation realm was consistently unnerving. It was violent. It could be scary. It was deadly. During that one-year tour, I flew 987 medevac missions, evacuated over 2,500 patients from both sides of the action, seven of my helicopters were shot up by enemy fire, and I was shot down twice. These were not unusual numbers for most Dust Off pilots. The seriousness of war became an intimate fact in a hurry. Perhaps that’s why our unarmed aircraft losses to enemy fire were 3.3 times that of all other forms of helicopter missions in that war. The possibility existed that we were literally in the shadow of death on every mission, just like the “grunts” on the ground.

The author standing beside a facsimile of their unit patch outside their orderly room on 7 Mar 70, after being promoted to unit commander at Red Beach in Da Nang. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

Dust-Off was the radio call sign used by U.S. Army Medical Service Corps flight crews. This name originated early in the war. Many people believe it originated from the dust our helicopters stirred up when we were landing. It’s actually an acronym that stands for Dedicated, Unhesitating Service To Our Fighting Forces. This name stuck for the rest of that conflict and is still being used today in current combat zones.

The risks were always obvious in our role of evacuating wounded from both sides of the action…and more often than not the dead. We collected their ravaged, burned, and broken bodies from innumerable village, rice paddy, and jungle locations. Then we flew them to aid stations, hospitals, hospital ships, or deposited their remains at the doorstep of Graves Registration next to our field site, battalion aid stations at Landing Zones Baldy and Hawk Hill, 25 and 32 miles south of Da Nang, respectively.

Constantly tight-roping the edge between life and death was similar to living in a nightmare that wouldn’t allow a person to wake up. These experiences will remain forever within the scar tissue of my mind. Many of these encounters had the ability to continuously spike my adrenaline level and create heart-clutching moments where I pretended to still be breathing.

This type of flying–always single ship ventures–was demanding. These missions were flown regardless of terrain, enemy action, or weather conditions both day and night. A rapid response and en route medical care could mean the difference between surviving or dying for American and allied troops, wounded and captured enemy soldiers, plus Vietnamese civilians alike. Through it all, flying and foot-slogging varieties of soldiers built mutual faith, trust, and respect through dependence on one another for survival encompassed by the devastation of combat.

The ghosts and memories from that Southeast Asian conflict continue to rattle their chains in my psyche. This is especially true of one unforgettable mission in early 1970 southwest of LZ Hawk Hill in the infamous Hiep Duc Valley of I Corps. Hardly a day passes, since then, when what occurred that morning doesn’t emerge front-and-center to replay itself in my mind like a needle stuck on a 78-rpm record. It was an experience that tested my resolve and authenticated my emotional decision for volunteering to become a Dust Off pilot in the first place.

The late WO1 J.B. Hill after being wounded in the hand on a Dust Off mission in March 1970. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

It was mid-morning and an infantry company had just been inserted by helicopters into an area about eight miles away. Two casualties had occurred, since they had landed in the middle of a Viet Cong battalion headquarters, knowingly or unknowingly. One slick helicopter had been shot down by .51-caliber anti-aircraft fire. The long, white mission sheet I was handed by our radio-telephone operator (RTO) noted that a second .51-cal was also out there somewhere. Our ground troops weren’t sure of its location. It said our patients would be located beside this downed bird and that’s where they wanted us to land. This was never encouraging news for a flight crew. A .51-cal round was capable of piercing just about anything, including our armored seats and twelve-pound Kevlar chest protectors that we referred to with dark humor as “chicken plates.”

A Dust Off aircraft commander develops a “sixth sense” after flying hundreds of missions into similar situations. As we neared their eight-digit ground coordinate, my eyes began taking in the terrain surrounding the landing area. A jungle-covered hill, jutting hundreds of feet high with an open area on top, was located to the west of the downed helicopter. If I’d have been the enemy, I thought, that’s where I’d probably have positioned a .51-caliber machine gun because it had a perfect view of any approaching aircraft. If my hunch was correct, I figured our best opportunity for survival would be to fly under it and risk small arms fire over a broader area. An enemy gunner on this hilltop wouldn’t be able to hit what he couldn’t see.

My copilot, the late WO1 J.B. Hill, identified the correct color of the smoke grenade the ground troops tossed out to mark where their wounded were waiting. This smoke also showed us the wind direction. That’s when I dumped the aircraft’s nose and began my diving and twisting tactical approach from 2,000 feet toward the west side of this hill. We reached ground level in a flash and I leveled off at 120 knots a few feet above a small stream that ran beneath this ridge and into the landing zone. Our Lycoming jet engine rumbled like thunder as we tore through this jungle terrain.

I kept the body and skids of our bird below the level of the trees. Our main rotor blades grazed the treetops on each side of the streambed. That’s when this mission took a drastic turn.

“We’re taking fire,” our medic stated, matter-of-factly, keying his mike switch behind me. “We’re taking hits.”

We were committed, as far as I was concerned, and there wasn’t going to be any turning back. Enemy small arms fire continued to erupt on all sides as we barreled into a large open area. I performed a “hot,” 180-degree turn from 120 knots–that we constantly practiced to save precious time–and stopped at a three-foot hover next to the downed helicopter, pointed toward our entry direction.

I could hear incoming enemy fire and outgoing covering fire. A few seconds elapsed as four crouching infantrymen shuffled toward us with their twin burdens of humanity.

“Get out of here, Dusty!” the ground RTO shouted into our headsets. “Incoming! Incoming!”

I heard and felt the “whoomp” of the first mortar round as it impacted not far behind us. Then another hit in front of us. I didn’t intend to hang around to see how this bracketing technique might culminate on a third attempt.

We managed to exit this landing zone with only a few holes in the helicopter to show for our effort, graphic reminders of the consequences of close combat.

At 2,000 feet, I gave the aircraft to J.B. and turned to check on the condition of our patients. Preoccupation with my own anxiety immediately disappeared, due to the sight of their physical misfortunes, and forced my emotional state into insignificance.

Their blood was dripping onto the cargo deck. Our medic and crew chief were working together to treat their injuries. Both wounded infantrymen appeared to be around nineteen years old. One had a sucking-chest wound. The other sat propped in a sitting position against the engine compartment bulkhead. His blue eyes were focused on mine and he appeared conscious, although he’d been wounded in the head by small arms fire.

“Sir, we gotta hurry,” our medic said over the intercom.

I nodded but instinctively knew no aircraft in existence could go fast enough to save him.

This blond-headed soldier’s lips moved and he said something to our medic. Moments later, his eyes appeared focused on something above me that no one else could see. I’d lived this scene so many times before. He’d departed for a place too distant to come back from. His war was over. Combat had terminated his existence before he’d barely had an opportunity to live it. Vietnam had become his lifetime.

I asked our medic what he’d said. His reply were words every medevac crew could ever hope to hear.

“Sir, he said ‘I knew you’d come and get me.'”

We had touched him briefly but he, in turn, would touch me for the rest of my life. He died with a thanks on his lips, even though he’d been wounded too seriously to be saved. His final statement has stayed with me to this day. Could we have gotten there faster or done something more that could have spared him?

In ‘Nam, the most common slang term for death was “wasted.” This was an accurate and appropriate choice of words. And we learned in a hurry that “buying the farm” in combat was different from its meaning back in Iowa. To experience war, and look it in the eye, is to acknowledge that there is still madness in the world even when the cause may be perceived as just.

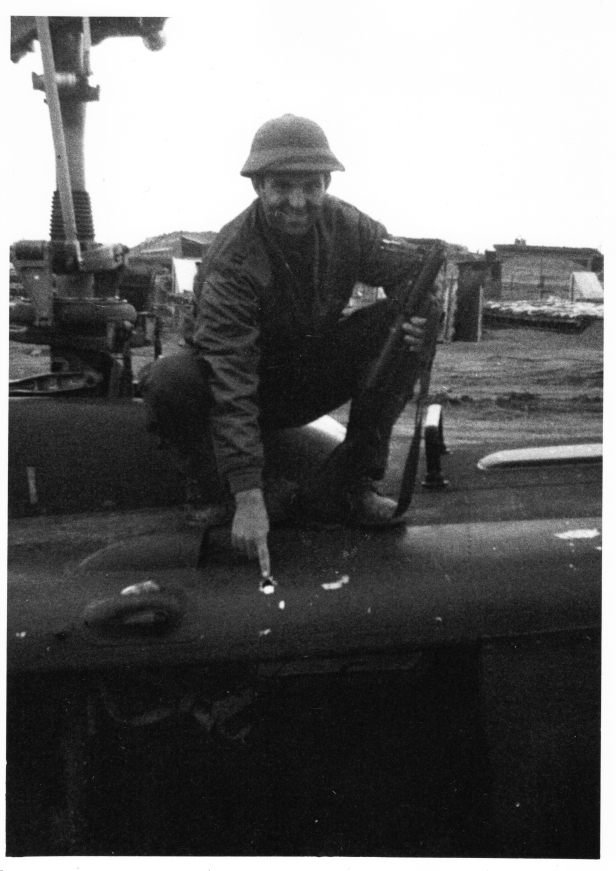

The author pointing to one of the bullet holes from the mission noted in this article, while wearing a captured NVA pith helmet and holding his M-79 grenade launcher at LZ Hawk Hill in early January 1970. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

For our flight crews there was the victory of endurance, the prize of persistence, and the triumph of tenacity if our patients survived as we carried out our missions. In my year in ‘Nam, all that our crewmembers and troops could count on were each other. We had a close bond. We provided our patients with hope, safety, and were often their only way out of critical and dangerous circumstances. Those on the ground would do anything to cover us and I never met a Dust Off pilot who wouldn’t risk a bird or a crew for them, regardless of the combat situation.

Saving everyone we went after was always our goal. I wish I could say that all those we were able to evacuate survived, but war isn’t a fairy tale. The final ending was not a pleasant one for millions of soldiers and civilians on either side of the action. For so many, war ate up their lives before they barely had an opportunity to live them.

In previous conflicts, a significant percentage of patients didn’t survive because helicopter support was not available and medical assistance arrived too late. And time, as the saying goes, is not only money but also equates to life and death when seriously wounded in warfare.

Not only have Dust Off crews read the combat book, we’ve also played supporting roles in the subsequent movie that was being filmed on location. We all flew for others. We flew to make a difference and to provide light to those who were momentarily lost and hurting in the darkness of battle. We offered our aircraft as a refuge for our patients, some of whom were destined to live a long time and others for a mere moment. It’s true, combat does provide a strong sensory experience with otherworld sights, sounds, and smells. It also made a vivid impression in my mind that all life is fragile. For many of the participants, this armed adventure also became their lifetime.

Each mission demanded determined decisions by the aircraft commander. These instantaneous human judgments provided either extended existence or a dramatic demise for patients and crewmembers. On the worst days, I didn’t expect to survive. But I kept at it. It constantly forced me to sift through the chaos of my daily existence for some semblance of order, stability, and rationality.

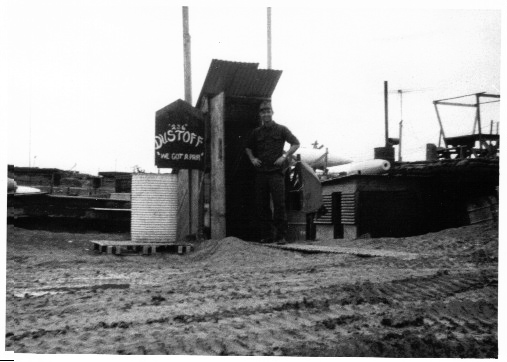

The author standing outside the door to the underground Dust Off hootch at LZ Hawk Hill in early 1970. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

For every patient we evacuated, there might be others we could never get to or help in time. We were constantly forced to confront invisible forces that we didn’t have the power to change or overcome. Death became matter-of-fact, even routine, in combat and it was something we couldn’t run away from. All we could do was to face the constant challenges, say a prayer, and allow our training, experience, instincts, and “guts” to kick-in. But we couldn’t expect an explanation about gross wounds that constantly surround soldiers in war or about devastating combat actions that occurred. A myriad of dangerous things occur in this twilight zone. They just happen. And we were forced to accept them as facts of life.

The sight of dead bodies stacked in a pile on our cargo compartment deck have created scars and ragged holes in my heart, soul, and psyche. For a long time, these traumatic scenes wouldn’t allow me to easily convey the emotions and pain buried deep within unless it was to another veteran who had been there.

During moments after battles on remote artillery bases, there would be enemy bodies strewn around the field of battle when we arrived to evacuate wounded survivors. Sometimes we landed at night in the middle of firefights featuring enemy mortars, AK-47s, flame throwers, rocket-propelled grenades, and satchel charges. It was always a surreal experience.

Everywhere we went, there would be an acrid odor of decaying flesh that was often combined with the overpowering stench of gas gangrene, vomit, feces, urine, blood, gunpowder, and napalm that permanently etched themselves into our weary brains. Eighteen, nineteen, and twenty-year-old crew members became accustomed to it like all the rest of us. It was merely a fact of life in that type of confrontational environment.

In Dust Off flying, there was nothing special we could do in the face of ominous death statistics except attempt to save others from this ultimate fate. As the son of a Protestant minister, I was raised to believe that God decides when a person’s final second comes. When it does arrive, there isn’t much anyone can do about it. It merely happens on its own. But all of us did the best we could at standing between our patients and a final rendezvous with Graves Registration.

Those young dead soldiers, civilian men, women, and children are now shadows that will continue to fall across my soul as long as God allows me to live. I witnessed hundreds and hundreds of them slip away like water through fingers day and night. Everyone dies. Sometime. Eventually. You can’t get out of it. No one is victorious over death in this life. Death always wins. Most of these people didn’t intend to die. It wasn’t on their day planners or anything. It simply transpired on its own. Many of those casualties probably thought they had lots of time left and the Grim Reaper wasn’t stalking them through rice paddies and jungle. But their hourglasses suddenly ran out of sand. In their specific cases, they were dead wrong.

It’s true. Vietnam was a 24-hour-a-day, real-life, drive-by shooting gallery…a very easy place to die. War is gruesome. It’s violent. It’s undignified. It wasn’t the way any rational person would envision meeting their Maker.

In every war, some people return intact and others don’t. My soul sorrow and ultimate survivor’s guilt at having witnessed so many dead and wounded, up close and personal, is not easily dismissed. As decades drift by, the emotional pain becomes less intense…but it never disappears. It’s as though I don’t want it to disappear because I never want to forget what I saw and experienced or those I met who were so vulnerable and courageous in battle.

As a pilot in the Dust Off business, I knew there were heavy odds that I might die doing my job. Yet what was more important to me was the kind of person I was in the face of that fact. Regardless of how our patients were wounded, or how bad, they were my responsibility as an aircraft commander. They were someone’s son or daughter, brother, sister, cousin, or close friend. That’s why I wasn’t afraid to take risks in an effort to give them an opportunity to be reunited with their loved ones again, because I knew my fellow flight crews and comrades on the ground would do the same for me.

In that year in Southeast Asia, I witnessed accidents, wounding, and deaths in nearly every way imaginable. There were also those other patients we carried suffering from snake bites, plague, leprosy, cholera, malaria, and a variety of other tropical diseases. As has been the case with soldiers in previous wars, such chaotic scenes, tragedies, and confrontational experiences are something I can’t expunge from my memory bank…even 50 years later. The sights, sounds, and smells of war may never disappear.

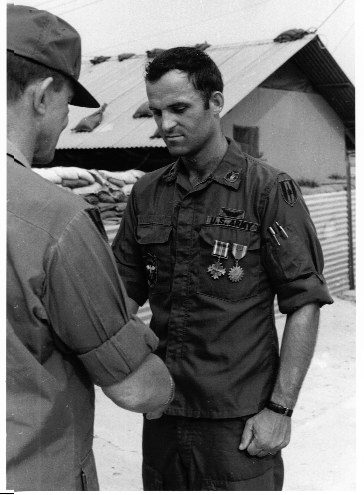

(L-R) The author and the late WO1 J.B. Hill, after receiving Vietnamese Crosses of Gallantry medals at an award ceremony at the Hoi An airfield in early 1970, for an earlier Dust Off mission involving ARVN soldiers. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

The following morning at Hawk Hill, after this young trooper had died on our aircraft, I was preflighting our Huey when an infantry staff sergeant walked up and asked if I was Dust Off 605.

“That I am,” I replied.

“Thanks for that mission you flew for two of our guys yesterday. You might like to know that later that afternoon, we discovered the tripod marks from an enemy .51-cal on the hilltop west of our landing zone. You flew right under it.” He didn’t say anything for a moment, as though he was trying to formulate the right words. Then a brief smile crossed his face as he said, “Sir, you guys are crazy!” before turning and walking away.

I’ll have to admit that this was undoubtedly one of the greatest compliments a Dust Off crew could ever receive, especially from a grunt.

Thinking back over those many years, perhaps my split second decision to fly low-level beneath that prominent terrain feature really may have saved us all.

From as early as I can remember, I’d wanted to be a pilot and military officer. America provided me with those opportunities. Our flight crews were trained to do what we did in Vietnam. We all took risks every day in an attempt to preserve soldier and civilian lives that were often extinguished in war as quickly as the flame of a candle that is plunged into water. We were in this deadly competition together, ’til death did us part, whether it was their time to go or ours. Sometimes there were moments when we were powerless to do anything about it…like that time. Yet even on death’s doorstep, this teenage infantryman had faith that we weren’t going to let him die alone.

War veterans have our own intimate memories of fallen comrades that have been stored, like squirrels stash their nuts, somewhere for safekeeping in the cache of our hearts. We reflect on their smiles in faded combat photographs we’ve kept in dresser drawers, a box under our bed, or in dusty closets. Their smiles are frozen in time during moments of better days…before they were no more. These were moments when what lay ahead was not yet known and couldn’t be known.

Five decades later, and after nineteen years as a medevac pilot on three continents, my life’s clock still ticks remorsefully on. I haven’t forgotten that young warrior or his untimely rendezvous with death. For me, his final words still echo down the long hallway of my memory. Although I never discovered his name or where he was from back in the “World,” I can still visualize him propped against our engine bulkhead, as six shades of green slipped by far below our open cargo compartment doors. It seems like it happened only yesterday, even though I’m now 77 years old. Sometimes all I can do is hold what’s left of those many combat experiences hoping that the emotional pain of this one particular remembrance will eventually subside as my own life slowly slips away. But, so far, much of this pain still remains.

That young hero has touched my life far more than I touched his. I will always be awed, motivated, grateful, and inspired by his courage and devotion to duty. In the end, I can only thank his parents and God for lending him to America, if only for a short nineteen years.

###

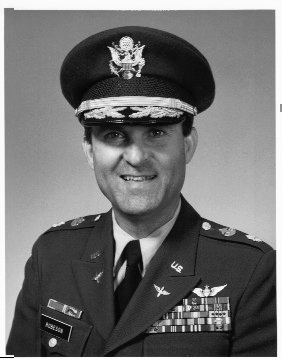

The author just prior to his military retirement, after over 27 years, on 31 Dec 87. (Photo courtesy of Robert Robeson.)

Robert Robeson has had his articles, short stories and poetry published over 900 times in 330 publications in 130 countries and 60 anthologies. This includes the Reader’s Digest, Writer’s Digest, Positive Living, Vietnam Combat, Soldier of Fortune (both American and Russian editions), Frontier Airline Magazine and Newsday, among others. He’s a life member of the National Writers Association, Veterans of Foreign Wars, Dustoff Association and the Distinguished Flying Cross Society. After retiring as a lieutenant colonel from a 27-year military career on three continents, he served as a newspaper managing editor and columnist. He has a BA in English from the University of Maryland–College Park and has completed extensive undergraduate and graduate work in journalism at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. He and his wife have been married for over 50 years.

Thank you, sir, for your service, sacrifice, and courage during our war. We are forever grateful and always knew that you’d come for us – no matter what. Thank you, too, for allowing me to post your article here on my website. / John

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I‘ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

Correction to Anonymous Oct 9, 0323 am post.

LikeLike

Served in Nam ’66, not combat vet. LTC Robeson’s account of his combat aircrew related experiences as an unarmed participant is obviously something I can’t relate to or the courage, fortitude, perseverance of his unit and of those superb combatants he saved and recovered. I am very grateful for his authoring his Nam experiences for the world.

[Did spend a day with former front-line Marines supporting local Vietnamese Popular Forces at Red Beach, on another occasion choppered to Phu Bai and Dong Ha for the day. In Spring we had mortar attack at DaNang, I was 20 y.o., that was scary. But none of that was combat. Know couple of Marine combat vets there in ’67 and ’70 and my duty shared a building with Marine unit. Always volunteered for Nam after my brief time there but instead got Thailand and Taiwan. By ’72 stopped volunteering but did TDY to NKP in Thailand in support of NVA Easter Offensive.

Volunteered for Desert Storm and Iraq (though against our involvement there as no WMD proof), was already retired from AD was not reactivated. Late in my enlisted career became a mustang.]

LikeLike

“A Miracle at LZ Ross” and “I Knew You’d Come” are both beautifully written. I too would like to say Thank You, Sir. I was a grunt RTO with C-4/12, 199th Infantry Brigade in Vietnam 1967 so I was involved with a number of Dustoffs for our guys. In a firefight on July 2, 1967 our 2nd platoon M-60 machine gunner was KIA and my squad leader and I were WIA. All three of us were on a Distoff from the Bien Hoa area to Tan Son Nhut airbase and then by ambulance to 3rd Field Hospital in Saigon.

LikeLike

Exceptional insight; Thanks for sharing…

LikeLike

I’ve read and forwarded this article of yours before. My brother was in Nam andmy girlfriend’s husband was a chopper pilot over there. Another friend of mine wasan Army Ranger who flew in those choppers over in Nam. But the new generation – in Afghanistan – includes an Army Rangernamed Joseph. Joseph has been over there as a medic, jumping out ofthe helicopters with a rifle in one hand and a medic bag in the other,triage work, then load up with the wounded and treat them on the wayback to base. When his wife was able to “Skype” him on a video line to tell Joseph thathe had been awarded another medal, his answer was: “I don’t deserve a medal. These guys I’m picking up with their brains blown out–they’rethe ones who deserve the medals.” He’s now being trained to be one of the helicopter pilotsfor “Dustoff” missions, so he’s home for a while, with his wife and hischildren. Please pray for Joseph. He will return over seas probably bythe end of this year.

LikeLiked by 1 person

W.C. “chuck” Ogle. Dustoff61

I flew with the 498th in1967-1968.

This article was an outstanding piece stating exactly what happened in Vietnam. There are things listed here that I have experienced, but could never put into words myself. Not only have I flown in many situations as described, and been shot down myself, but the memories of fellow crew members that were lost during that tour still haunt me today. Thank you for such a greatly written article. It was a little hard to read as it brought back many good and bad memories that I’ve kept locked up inside that maybe I needed to get out. Again thank you and Welcome Home!!

LikeLike

Hi Chuck,

Al Flory and I came down to the 498th from the 54th in late Jan 68. My call sign was Dustoff 29. We may have flown together, I don’t remember everyone.

Allan Scott

LikeLike

Excellent journalism. Always enjoy reading Bob’s articles. Accurate and realistic.

LikeLike

Stories such as this bring back the worst of war. I was a grunt with the 1st/7th Cav from July of 69 to July of 70. I will 2nd the compliment about you chopper pilots being crazy, but there were many times it sure came in handy!! Thank you!!

LikeLike

As a former Dustoff pilot myself with the 498th, the story hit home and resurrected some memories, thanks for sharing. The area I mostly covered was Nha Trang, Dong Ba Thinh, Bam me Tuit, Anh Khe and LZ English and Uplift, also around Tuy Hoa when with a smaller detachment that was infused into the 498th that was out of Lane near Quin Nhon. Had some pretty interesting missions, and we did carry sixties in the wells.

LikeLike

I was on LZ Hawkhill for all of 1970. I was also on LZ Baldy hooking water blivets to LZ Center and Siberia.

I was a young 20 year old smart ass. That didn’t last long.

HHB 3/82nd Arty

Welcome Home Brothers and Sisters.

LikeLike

Its beautifully written and hit me, as an old grunt with the 1st Infantry Division, right in the gut. The memories came back rapidly, mostly of the adrenal rushing all the time and the horrible faces of death that became a daily thing. I was “Dusted Off” myself and know the quality, devotion and bravery of those guys and their medics and crew members. Sometimes now (50 plus years later) all I can capture in my awake brain are snapshots of things and memories of the day to day. moment to moment chaos. It’s when I try tp sleep at night that the worst movies run in my head and take me back there.

LikeLike

Thank you sir! From a grunt Medic with the 2/7 Cav 67-69

As with so many memories

I loaded up the Medivac birds with the wounded until I thought they would fall out of the sky—and then put more on! I would see those birds use their rotating prop to cut out the jungle just like a lawn mower. I saw the chopper pilots defy death over and over as they lined up to rescue and provide hope to those of us on the ground. These choppers with their special Pilots amazed us with their flying ability and did things out of necessity demanded by war and the need to save serve and deliver the American grunts to the assigned A.O. as well as to bring help and hope to those of us that were more than medically challenged. These Chopper pilots were and are beyond the ordinary as noted by their outstanding bravery that became ordinary as an example of those of un-ordinary caliber, which developed a standard for those that were beyond the ordinary.

LikeLike

Can anyone out there help us find a helicopter pilot who went by name Arizona….was there April 21 1971…. flew in to supply platoon that was under fire. Looking for a few yrs now for him for Lt Frank Guidara, aka Duke. Would mean the world to him to find him.

LikeLike

Fantastic article,I was also in Country in 69 to 70,I had to be medevacked out,I’ll be forever grateful and in awe at the pure courage and guts thease pilots had,no one took more risks the the dust off chopper pilots,thank you, to all the great pilots who risked their lives for us grunts!

LikeLike

I’m not sure I’ve ever in my life felt more grateful to anyone than I did to the medic and crew of the slick that medevacked me. That happened during Captain Robeson’s tour. So let me add my thanks to those of the many other grunts pulled from death’s door by these helicopter ambulance drivers!

LikeLike

This Disabled VIETNAM Veteran sends his heart of Love. “GOOD BLESS”

LikeLike

We always knew you would come. Thanks, Dustoff crews.

173d Abn 1965-1968 PH

LikeLike

Excellent read! Many thanks to John Podlaski and Robert Robeson. I have been a member of a PTSD group at our local Vet Center for a few years. I have heard comments from my fellow members who happened to be army or marine veterans from the AO supported by the 236 MED DET and Naval Ships. They have echoed the same commentary: ” I knew you would come ” That is one reason That many veterans are more patriotic than others. I was in a place where we were not sure when and if anyone would come. I am pleased to know what “Dust off” means – we had two phrases: Medivac for the US WIA and Dust Off for the US KIA. The enemy WIA and KIA were left to rot.

LikeLike

Tremendously Emotional Article. I hope that expressing himself and sharing his deepest fears will help Lt. Col, Robeson come to grips with the horrors of war that torment others so hard..

LikeLike

Fantastic article!!! While stationed at Tan Son Nhut, there was always a lot of chopper activity across the road from the main gate. Two helo landing pads also the 3rd Field Hospital, Any helo inbound to the landing pads had an emergency case aboard. There was a tree line by the pads and charlie would sneak in to shoot at the dust offs. This was especially so at night with their landing lights on. No where was safe in NAM!! If charlie was known to be in the tree line, the main gate personnel would open up with their 50s/60s. Light up charlie, Once secure, the helos would land with their precious cargo.

LikeLike

Best piece I have ever read by an officer. He got the feel of the fighting Joe down just right with his total immersion…into humanity.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Great post!

Change of Email Address

Would you please change my email address in your system to the following:

amb77@bigpond.com

Thank you

Best wishes, tony

Tony Brown

BEc, GDES, LLB(Hons) GDLP

Sessional Lecturer

PhD (Law) Scholar

Faculty of Business & Law

Conjoint Fellow School of Medicine and Public Health

University of Newcastle, NSW Australia

+61 448100669

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tony, I’m unable to do anything with the email addresses and you’ll have to sign up again with your new address.

LikeLike

I can say, from the time I arrived in the Nam. I constantly heard the Chopper sound. The Chopper Pilots were like all the rest, of us. I believe, without them. There would be a greater number of, killed. Would be higher than, 58,479. My last word is, we really had no business, even entering in to that FIASCO.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am now, entering my Date & Time of arrival. Early in May I think about the 7th. We landed in TanSonhut near Saigon. it’s been so long, the actual Date, I have forgotten.

LikeLiked by 1 person