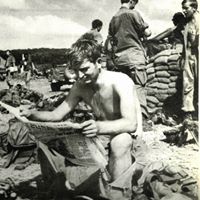

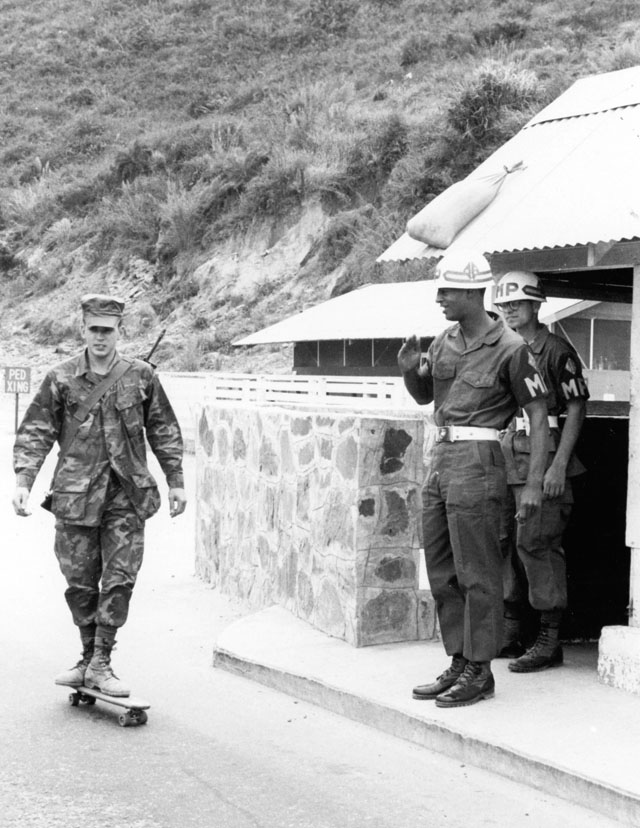

A Marine private tries out a skateboard sent from home. Soldiers behind the lines often had lots of downtime. (Sgt. Licciardi/U.S. Marine Corps/National Archives)

John Winter recently posted this article on Facebook within the group: Vietnam Memories: Past/Present – I’ve copied it here for you to read. One thing I disagree with right off the back is that there was no place recognized as “behind the lines” in the Vietnam War; soldiers were at risk everywhere. It’s just that some places were safer and more homey than others.

Specialist Howard distinguished himself with conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life when he single-handedly answered over 200 telephone calls and processed in fifteen new men, exposing himself to a hail of questions. He moved from the relative safety of his desk to the P.X. where he repeatedly bought cases of soda. He organized and led his section as they swept out their hootch. Ignoring the personnel NCO, he cleaned his typewriter, picked up the mail, petted four dogs, ran off three stencils and took his malaria pill.

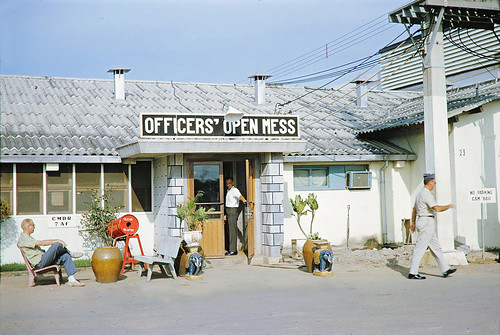

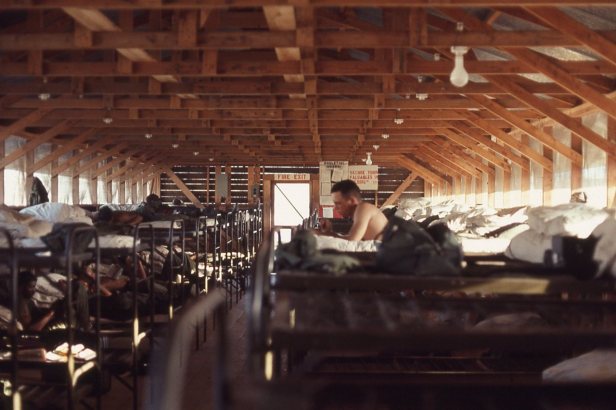

Modern armies have always required mammoth support operations. But Vietnam was different. For the first time, the U.S. military turned its rearward bases into replicas of home, with many of the luxuries and consumer goods that post–World War II prosperity had lavished on America. The abundance had an unintended side effect: The uneven distribution of discomfort and danger stoked combat soldiers’ resentment of support troops, who were derided as “rear echelon motherfuckers.” REMFs and grunts may have served on the same side, but they did not serve in the same war.

By 1972, Long Binh Post even had a go-cart track, complete with a starting stand, a public-address system, and a pit for on-the-spot repairs.

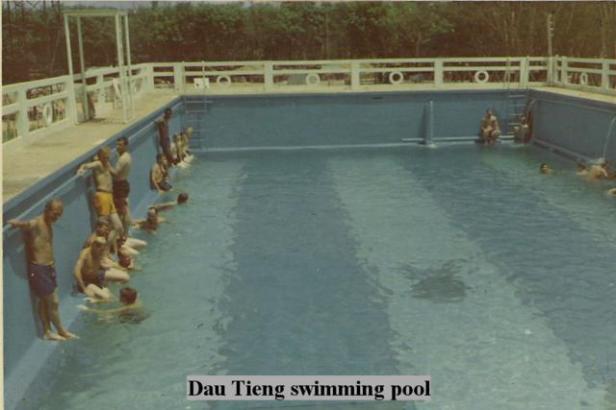

Construction of new recreational facilities on Long Binh Post continued until the end of the war. As late as 1970, more than a year into troop withdrawals from Vietnam, the U.S. Army was still planning to build two 474-seat movie theaters, additional handball courts, two in-ground swimming pools with bathhouses, and a recreational lake. The military scrapped the more expensive construction projects in response to public outrage, but the post’s amenities were still expanding right through the summer of 1971.

SUCH ABUNDANCE combined with the relative safety of duty in the rear to make the war itself seem like a distant concern. Writing about Da Nang Air Base in his memoir, Vietnam: The Other War, military policeman Charles Anderson reflects on this sense of isolation: “All of these comforts and services made the world of the rear a warm, insulated, womb-capsule into which the sweaty, grimy, screaming, bleeding, writhing-in-the-hot-dust thing that was the war rarely intruded.” William Upton, who served near the R&R center at Vung Tàu, told his mother upon returning home, “Most of the time you didn’t know you were in a war.”

Though U.S. Army officials denied friction between combat and support troops, front-line soldiers bristled at how their peers lived. In his memoir Nam Sense: Surviving Vietnam with the 101st Airborne, Arthur Wiknik Jr.—an infantry squad leader and veteran of the bloody assault on Hamburger Hill—seethes: “As near as I could tell, the only danger a REMF faced was from catching gonorrhea or being run down by a drunken truck driver. And the biggest hardship a REMF contended with was when a generator broke down and [his] beer got warm or there was no movie that night.”

In April 1969, 30 members of a combat infantry unit aired their grievances publicly. Writing to President Richard M. Nixon, they argued that “basically there are two different wars here in Vietnam. While we are out in the field living like animals, putting our lives on the line twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, the guy in the rear’s biggest problem is that he can receive only one television station. There is no comparison between the two….The man in the rear doesn’t know what it is like to burn a leech off his body with a cigarette; to go unbathed for months at a time…or to wake up to the sound of incoming mortar rounds and the cry of your buddy screaming, ‘Medic!’”

A year later, retired officer John H. Funston wrote to the New York Times arguing that the army should reward riflemen with extra pay for the hazards they face in the field. The idea of combat pay, he argued, had been trivialized because every soldier received it, “regardless of his rank or whether he is a rifleman being shot at or a lifeguard at a rest area swimming pool.”

SOLDIERS IN THE REAR, meanwhile, regarded combat troops with deep admiration. On his way to an overseas R&R, clerk-typist Dean Muehlberg encountered a company of infantrymen on stand-down at the out-processing center at Da Nang. “We were in awe of the Marines,” he gushed. “We didn’t speak to them or get in their way. We didn’t know their language. You sensed that after the constant threat of death, of terrible harm, nothing else scared them.”

Muehlberg wrote a memoir, REMF “War Stories,” in which he pokes fun at himself, the boring work, and the very idea that he was fighting a war. The quotation marks in the title are deliberate; his 1969 tour was so far removed from combat that his rifle actually grew mold while it sat in its rack.

Muehlberg worked in the Awards and Decorations section, where he processed recommendations for medals and decided what commendation was appropriate. “For the first month it seemed a dirty job,” he writes. “I did not feel worthy! I was sitting in relative security reading grisly, awe-inspiring accounts of the courage of my not so fortunate brothers who were out in the thick of it. And then sitting in judgment on the ‘degree’ of their courage, their deed.”

After the war, enmity between grunts and REMFs persisted in personal memoirs and, later, websites. But in some cases, grunts’ bitterness lost its edge as veterans closed ranks to face a common enemy upon returning home: public and government indifference. Those who joined protests as part of the G.I. movement to end the war and claim federal veterans benefits buried their bad feelings in order to increase their numbers and present a unified front. Thousands of REMFs marched alongside combat veterans. Antiwar veteran groups scarcely acknowledged that the divisions ever existed. To the public, all the returning soldiers were simply “Vietnam veterans.” Only the vets knew that they had served on the same side in different wars.

Adapted from Armed With Abundance: Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam War, by Meredith H. Lair, assistant professor of history at George Mason University in Virginia. © 2011 by The University of North Carolina Press.

This story originally posted on the Historynet dot com website on 5/12/2012 by Merideth Lair. Here is the direct link: https://www.historynet.com/easy-living-in-a-hard-war-behind-the-lines-in-vietnam.htm?fbclid=IwAR3gEUe8ZhyI-GX08N6rwNFcaGKfoaOmBzlHr_kRk-r52c97gCi2D2UFCKg

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

Served with the 11th Cav in Xuan Loc 66/67 part of 37th Med Co support hospital…. And being a REMF had no bearing on our services. We treated, went into the field in choppers, pulled that dreaded “guard duty” and ferried seriously wounded to the 93rd Evac in Bien Hoa. 3 million troops went in that time frame …. 58,479 didn’t get back …. Took me 30 years to realize my opinions in a local newspaper, but, being in my role, I respected those “front liners”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Any new arrivals had a one chance in four to see combat. I did not know that at the time but just went where the Army to me to go. I had an Avionics Mos background and went to Vinh Long on the Mekong Delta. I was age 19, did not attend jungle school like a lot of the other guys. Got issued jungle boots with the metal plate in the sole. Spent the entire 13 months there, became a Huey door gunner due to a lack of personnel. I learned how to kill people, better them than me. Still trying to live with that!

LikeLike

Most employers required a DD214 or proof of deferment. My MOS was sniper team leader. I was told by many “we have all the snipers we need right now, if you had been a truck driver or mechanic we would have something for you” The VVA held a town hall on agent orange at my local VAMC – I had a blue water navy guy on my left and an interpreter on my right. The REMFs are still getting over. I still don’t like them breathing the same air as me. Not my brothers.

LikeLike

Well everyone had a job to do in the Nam.I can see why the Grunts had a problem with Guy’s that worked in the rear. But what i don’t get is not everyone in the Rear had it made. I served with The 11thacrBlackhorse mostly in the rear Base Camp in Xuan-Loc/Long Giao 67/68. We were almost always surranded by the Enemy VC and NVA matter of fact our base Blackhorse had a Tunnell complex all the way thru like at Chu Che 25th Inf Base. Anyway we had to carry our Weapons at all times we pulled Bunker Guard on the Primater and Ambush Patrols in the Rubber Trees and in the Jungle surranding Blackhorse.Also the VC planted Mines up and down the Hwy QL 2 from Blackhorse to Xuan-Loc. There were several other Infantry Units that operated out of Blackhorse one being The 199th Inf Red Catchers patroled outside the wire in the Rubber and the Jungle between the Cavalry Trails APC’S and Tanks made by the 11thacr.They said that the VC and NVA were dug in and had been there for years. We also had FSB Libbly about a mile or so down Hwy QL2 everytime the 11thcav or the 199th Red Catchers would go in there would be a Fire Fight. In closeing Xuan-Loc was almost wiped out during TET 68 and the Last Battle was fought in 1975 between Xuan-Loc and Blackhorse they say dead Body’s all up and down QL2. So not all as everyone calls it REMF’S had it that good. Godbless RonaldERaper

LikeLike

probably true i spent 9 months in the bush and never had an r&R would leave my brothers

LikeLike

Been up to Dau Tieng swimming pool a number of times since around 1992. Last time was last year. They’ve improved it from what it was in the 90s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I always felt a bit guilty, flying off an aircraft carrier to provide close air support for our guys on the ground. I could go back to the ship, have a hot meal and a warm bunk. I knew these guys under fire had no such accommodations when in the bush and night fell.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You go where you were sent. MOS had something to do with it of course. I don’t think hardly anyone really wanted to be there anyway. That’s the way the military works. MACVJ2.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot of people thought that I was crazy because I did a 1049 for Vietnam because I didn’t like Germany. I was TDY on a CMMI inspection team. I didn’t like living out of a suitcase 5 days a week. I am one of the few who wanted to be there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Landed in vietnam at 0430 just a kid we got hit. You would be surprised what goes through your mind. Never smelled shit burn, never came that close to death that fast. I heard someone say welcome to the name. Rode on buses with screen wire windows MP jeeps with m60’s. Than it was time to go home what a greeting, that was almost as bad as getting hit. Still kind of a half kid but a wide awake man. Than I landed in San Francisco guy on my flight was sick parked on the tarmac for 4 hours. Missed my plane slept on my duffle for 8 hours. Met some guys went to the bar we ordered drinks but not for me I was 20 years old. I will leave it at that.

Thanks

LikeLike

I was a heavy artillery mechanic on the 175mm and 8in howitzers in northern I Corp area. Although my bed was in Dong Ha I was in the field probably 5 or 6 days a week. Looking back at the War I can see the resentment that the guys living in the field might have. Dong Ha didn’t have a lot of the immentes that was mentioned in your article, it was better than living under ground in a bunker. We had an R & R (Repair & Return ) set up for the howitzers. We would do some PM on the guns for a week. This would give the gun crew a break from the field. I liked going to the field to work on the guns.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was an air force dog handler with the 3rd sps at bien hoa from may 69 to dec 70. dangerous at times but relatively safe except during rocket and mortar attacks when we had no where to go. I thank all my army and marine buddies for their heroism. God Bless and welcome home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I done lift 1 massg.be for I read all the shit in the rest

I was 17 years old when I got to v nam in 65/66 we cleaned camp Radcliff for the 1st cab. The1st week I was put in a fox hole with M/ 79 with no ammo all most every night the VC would fire red /green tracer at us .I was with 625 D/S co. We did c rates water puref. J.p.4 and grave regulations. So please don’t put us all in that category I’m proud of my service in V M but it still BULL SHIT what you saying with tears coming up I’ll shut up but I’ll never forget the heroes I bagged / tagged to go home

.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was Construction Engineer. Our mission was to rebuild, mostly, QL 1 highway. And while I only encountered 3 episodes of shooting at me, none were horrific as those in certain areas if Vietnam. But, I take issue with a good portion of the goodness the author outlined, as far as my experience from Nov 1967 thru Nov 1969. The places I visited were mostly TDY to other outfits to help build their needs/fortifications.

Unit was stationed in Nha Trang but my group was seldom there. We ran a rock quarry in small village across from Cam Rhan Bay. Eat food sent in. Was in several places out in the country. Went TDY with Vermont National Guard. Where? Never really knew. Just a place where dirt was pushed up for bunkers & living spaces. The faces on those soldiers coming in from night patrol were indescribable.

Phantom Thiet was were I ETS from. Were building our camp on mountain side while living on beach next to 101st Airborne group. Wasn’t good neighborhood. Guy got blown out of his vehicle coming back to beach as 1st vehicle out that morning as ran over mine placed there overnight.

So, lots of REMFs didnt see or partake of the excesses outlined in authors story. Didnt mean we wouldnt hsve fought if called upon but (U.S. Army took me out of 11B) they wanted me to do another job they had.

I went as requested, to serve my country, as my father did for 25 yrs in the A.F. Dont think I nor those like me m, deserve the negativity of this story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

On Sun, Sep 1, 2019, 2:03 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

> pdoggbiker posted: ” A Marine private tries out a skateboard sent from > home. Soldiers behind the lines often had lots of downtime. (Sgt. > Licciardi/U.S. Marine Corps/National Archives) John Winter recently posted > this article on Facebook within the group: Vietnam Mem” >

LikeLiked by 1 person

Nice article, contrasting The Cutting Edge of the Armed Force to the logistic tail that stretches back to the training camps and Supply Centers of the United States. Nobody in the Supply Centers suffered from PTSD. But it was endemic for The Cutting Edge to have to confront the enemy face-to-face and destroy or be destroyed, no matter what their age or race or gender might be.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I humped in that jungle for ten months with the 1st. Air Cavalry. We stayed out there for about 26 days a month. Making contact with the NVA on an average of 18-21 days usually getting ambushed first. We then would get extracted to a fire base for some hot meals, clean clothes, s shower (cold) and maybe a couple of warm beers. Yeah , life was quite a bit different for us in the 1st. Cav. Luck of the draw. I saw the guys at the rear AF pilots, cooks, clerks, bouncers at the clubs..It don’t mean nothing” The real heroes never came home!

“War is Hell” but “Combat is a Mother Fucker” ..we all said these quotes.. I have no regrets.. I am blessed..

LikeLiked by 1 person

One more thing, when in combat on a daily basis, I never visited those resort locations. We had a job to do and had no time to play! My M14 was in my rack with me at all times. Death was all around, handling the bodies was the hard part. Those memories will never go away. Ron

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never had time to think about the rear guys, just trying to stay alive as a Huey door gunner in a Vinh Long, Mekong Delta. Only injured once!

LikeLiked by 1 person

GOD BLESS YOU, MY BROTHER, GLAD YOU WERE UNINJURED AND CAME HOME IN GOOD SHAPE, LONG BINH, WAS NOT WITHOUT ITS DANGERS, WE HAD 24/7 MORTAR AND ROCKET ATTACKS, WAS TRULY FRIGHTENING AND BEING NEXT DOOR TO CU CHI WE WERE ALWAYS IN DANGER FOR THE WOMEN AT LONG BINH, WAC COMPOUND AND WE DID NOT EVEN HAVE ANY WEAPONS TO PROTECT OURSELVES, SO IT WAS NOT WITHOUT ITS DANGERS, AS I SAID EARLIER, , LONG BINH, VIETNAM, 1968-1969, KUI.

LikeLike

As a grunt in the 4th infantry , I think one of the things that irritated me the most about coming out of the field for a few days to a base camp, was the fact that we still almost always had to pull guard while the REMF’S could get a break. That wasn’t the case exclusively but after spending weeks/ months in the boonies and having to still pull guard that sucked big time. I also do know there were guys in the rear that helped us out in many ways whether it was mail, a change of jungle fatigues every so often, or Hots once in a while etc. so I give them credit for backing us up that way.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Never thought of REMFs except to list all the vital jobs they did — armorer, supply, mail, c-rates, new equpment … list goes on and on. If they slept in beds and got laid every so often, good for them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I went to beginning and Gordon on 68 11b air mobile got to Vietnam on December 28 stayed 30 days in the 90th for guard duty lift there went to the 11th black horse stayed there for a month then got sent to can toe for security for some transportation 565later the 440th went to some remote base further in the delta and became an overwrite leap bid that for a month then went to John long in May and stayed there until I lift in March 70 , so after all this run around I stayed in chin London as security for the 440th trans,it just seems a big waist of time of time for me with all the hard trading I had but I guess I saw both sides of that war one from the Bush and one from the team’s .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was in total shock walking through Ton Son Nhut air base seeing paved roads, sidewalks, movie theaters and clubs with live bands after spending two months on the rivers and canals of the delta on. a 50 Swiftboat. Thank you for telling about the differences.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Saigon had it all, even military items on the streets. They kept me in the bush for 99 percent of the time. I was not aware of the bases with the swimming pools, etc. We did have a mud pit to swim in a Vinh Long, 1965. Door gunner and Avionics was my job, all I wanted to do was stay alive and come home. I did get injured during one fire fight, 20 percent disability today. I am 74 years old now, trying to forget that useless war.

LikeLike

When ever we retuned to base we wouldn’t even talk to those jerk-offs! 1stCav Airmobile Sent from my iPad

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

It hit the nail on the head.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cpl Bob Meadows H company 2/5 1stMarine Division 1967 to 1968 the first time I got wounded was in Hue city Feb 3 1968 I was med vac to Danang where I spent 7 days in the Hospital I had orders to go to hill 327 to the Morgue and id marines from my unit and pick up personal Idems then catch a chopper back to Hue city. I did a lot of walking from the Hospital and would flag down a ride every now and then I didn’t have a weapon and man was I a little scared I would see Marines in the rear and they acted like there wasn’t a war going on and this was in the TET 68 I finally got to da-nang air base 2 6 bys came in loaded with NVA prisoners I over heard one of the air force men say I would give anything for a helmet to take home I just shook my head finally caught my chopper to Phu Bia and then one to Hue City I was wounded 2 more times one Hell of a fight. two different wars I dont hold any feelings everyone had a job to do.

LikeLiked by 1 person