To ask when the Vietnam War started for the United States is, metaphorically speaking, to open a can of worms. Before 1950, it was clear that the United States was not engaged in the war in any serious way. After 28 July 1965, it became equally clear that the United States had indeed become engaged in the war. Between these two dates, various competing narratives exist to bedevil and perplex citizen and historian attempting to answer what might seem to be either a simple or a trick question: when did the Vietnam War start for the United States? Some argue that we moved into the war incrementally. To these individuals, no single moment exists when one can say definitively that the United States was, at least not until July 1965. Instead, a series of steps moved the United States closer to war. Others believe that a specific date and event in this 15-year period can be isolated and identified as the time when the war actually started for the United States. What follows is a chronological list of possible dates suggesting when the war started for the United States, a brief analysis of each, and a few concluding remarks.

The following is taken from the three posters offered by Vietnam War 50th anniversary. This link will take you to the site of these posters and others that are offered: http://www.vietnamwar50th.com/education/posters/

September 2, 1945:

Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese nationalist who admired the works of Marx and wanted to establish a socialist state in his country, issues a “Declaration of Independence,” borrowing language from the U.S. Declaration and stating, “…we, members of the Provisional Government, representing the whole Vietnamese people, declare that from now on we break off all relations of a colonial character with France.” Although France would initially acknowledge this Declaration of Independence, the stage was set for what would become a decade long conflict between France and Ho Chi Min’s communist-backed Viet Minh forces.

January 14, 1950:

The People’s Republic of China formally recognized Ho Chi Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam and began sending military advisers, modern weapons and equipment to the Viet Minh. Later in January, the Soviet Union extended diplomatic recognition of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

The People’s Republic of China formally recognized Ho Chi Minh’s Democratic Republic of Vietnam and began sending military advisers, modern weapons and equipment to the Viet Minh. Later in January, the Soviet Union extended diplomatic recognition of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

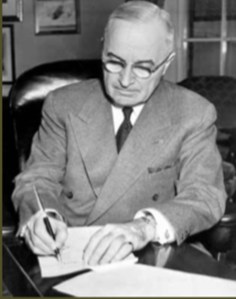

February 27, 1950:

President Truman signs NSC 64, a memorandum that recommended “that all practicable measures be taken” to check further communist expansion in Southeast Asia.

President Truman signs NSC 64, a memorandum that recommended “that all practicable measures be taken” to check further communist expansion in Southeast Asia.

May 8, 1950:

United States announces that it was “according economic aid and military equipment to the associated states of Indochina and to France in order to assist them in restoring stability and permitting these states to pursue their peaceful and democratic development.”

September 17, 1950:

United States establishes the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Indochina, in Saigon. Its primary function was to manage American military aid to and through France to the Associated States of Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) to combat communist forces.

May 7, 1954:

The conflict between French forces and the Viet Minh culminated in the battle at Dien Bien Phu. Between March 13 and May 6, 1954, CIA contracted pilots and crews made 682 airdrops to the beleaguered French forces. On May 7, French forces surrendered to the Viet Minh after a 55 day battle, marking the end to France’s attempt to hold on to its colonial possession.

The conflict between French forces and the Viet Minh culminated in the battle at Dien Bien Phu. Between March 13 and May 6, 1954, CIA contracted pilots and crews made 682 airdrops to the beleaguered French forces. On May 7, French forces surrendered to the Viet Minh after a 55 day battle, marking the end to France’s attempt to hold on to its colonial possession.

July 20, 1954:

The French defeat at Dien Bien Phu led to the Geneva Accords which established a cease-fire in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam and divided the country into a North and South Vietnam with a demilitarized zone along the 17th Parallel. French forces had to withdraw south of the parallel, the Viet Minh withdrew north of it. Within two years, a general election was to be held in both north and south for a single national government.

The French defeat at Dien Bien Phu led to the Geneva Accords which established a cease-fire in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam and divided the country into a North and South Vietnam with a demilitarized zone along the 17th Parallel. French forces had to withdraw south of the parallel, the Viet Minh withdrew north of it. Within two years, a general election was to be held in both north and south for a single national government.

September 8, 1954:

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) is formed as a military alliance to check communist expansion, and included France, Great Britain, United States, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan.

Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) is formed as a military alliance to check communist expansion, and included France, Great Britain, United States, Australia, New Zealand, the Philippines, Thailand, and Pakistan.

November 1, 1955:

By 1955, France had given up its military advisory responsibilities in South Vietnam, and the United States assumed the task. To appropriately focus on its new role, on November 1 the United States redesignated MAAG, Indo-china as MAAG, Vietnam and created a MAAG, Cambodia. MAAG, Vietnam then became the main conduit for American military assistance to South Vietnam and the organization responsible for advising and training the South Vietnamese military.

By 1955, France had given up its military advisory responsibilities in South Vietnam, and the United States assumed the task. To appropriately focus on its new role, on November 1 the United States redesignated MAAG, Indo-china as MAAG, Vietnam and created a MAAG, Cambodia. MAAG, Vietnam then became the main conduit for American military assistance to South Vietnam and the organization responsible for advising and training the South Vietnamese military.

November 11, 1961:

In the face of South Vietnam’s failure to defeat the communist insurgency and the increasing possibility that the insurgency might succeed, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recommend to President John F. Kennedy, “to commit ourselves to the objective of preventing the fall of South Viet-Nam to Communism and that, in so doing so, …recognize that…the United States and other SEATO forces may be necessary to achieve this objective.”

In the face of South Vietnam’s failure to defeat the communist insurgency and the increasing possibility that the insurgency might succeed, Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara recommend to President John F. Kennedy, “to commit ourselves to the objective of preventing the fall of South Viet-Nam to Communism and that, in so doing so, …recognize that…the United States and other SEATO forces may be necessary to achieve this objective.”

November 22, 1961:

President Kennedy substantially increased the level of U.S. military assistance to Vietnam. National Security Action Memorandum 111, dated November 22, stated that: “The U.S. Government is prepared to join the Viet-Nam Government in a sharply increased joint effort to avoid a further deterioration in the situation in South Viet Nam.”

December 11, 1961:

Kennedy’s decision resulted in sending to South Vietnam the USNS Core with men and materiel aboard (32 Vertol H–21C Shawnee helicopters and 400 air and ground crewmen to operate and maintain them). Less than two weeks later, the helicopters, flown by U.S. pilots, would provide combat support in an operation west of Saigon.

Kennedy’s decision resulted in sending to South Vietnam the USNS Core with men and materiel aboard (32 Vertol H–21C Shawnee helicopters and 400 air and ground crewmen to operate and maintain them). Less than two weeks later, the helicopters, flown by U.S. pilots, would provide combat support in an operation west of Saigon.

February 8, 1962:

Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) is created and commanded by General Paul D. Harkins. Henceforth, MACV directed the conduct of the war and supervised Military Assistance and Advisory Group-Vietnam.

‘

November 22, 1963:

President Lyndon B. Johnson is sworn in as President, following the assassination of President Kennedy. U.S. policy vis-a-vis Vietnam would change dramatically under Johnson’s Administration.

August 7, 1964:

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the USS Maddox, a Navy destroyer, off the coast of North Vietnam. Two days later, a second attack was reported on another destroyer, although it is now accepted that the second attack did not occur. In the wake of these attacks, President Lyndon Johnson presented a resolution to Congress, which voted overwhelmingly in favor on August 7. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution stated that “Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

On August 2, 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the USS Maddox, a Navy destroyer, off the coast of North Vietnam. Two days later, a second attack was reported on another destroyer, although it is now accepted that the second attack did not occur. In the wake of these attacks, President Lyndon Johnson presented a resolution to Congress, which voted overwhelmingly in favor on August 7. The Tonkin Gulf Resolution stated that “Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”

March 2, 1965:

U.S. military aircraft begin attacking targets throughout North Vietnam in the strategic bombing campaign—Operation ROLLING THUNDER.

U.S. military aircraft begin attacking targets throughout North Vietnam in the strategic bombing campaign—Operation ROLLING THUNDER.

‘

March 8, 1965:

As the situation deteriorated in South Vietnam and the United States ramped up its air war activities there, the Da Nang air base in northern South Vietnam became both significant to those activities and vulnerable to attack by communist insurgents, the Viet Cong. To defend the air base, but specifically not to carry out offensive operations against the Viet Cong, President Johnson authorized the landing of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, about 5,000 strong, at Da Nang on March 8.

As the situation deteriorated in South Vietnam and the United States ramped up its air war activities there, the Da Nang air base in northern South Vietnam became both significant to those activities and vulnerable to attack by communist insurgents, the Viet Cong. To defend the air base, but specifically not to carry out offensive operations against the Viet Cong, President Johnson authorized the landing of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, about 5,000 strong, at Da Nang on March 8.

July 28, 1965:

By May 1965, the situation had so deteriorated in South Vietnam that General William C. Westmoreland concluded that American combat troops had to enter the conflict as combatants, or else South Vietnam would collapse within six months. Johnson announced his decision at a press conference on July 28: “We will not surrender and we will not retreat…we are going to continue to persist, if persist we must, until death and desolation have led to the same [peace] conference table where others could now join us at a much smaller cost.” On the same day he ordered the 1st Cavalry Division, Airmobile to Vietnam, with more units to follow. The United States was now fully committed.

By May 1965, the situation had so deteriorated in South Vietnam that General William C. Westmoreland concluded that American combat troops had to enter the conflict as combatants, or else South Vietnam would collapse within six months. Johnson announced his decision at a press conference on July 28: “We will not surrender and we will not retreat…we are going to continue to persist, if persist we must, until death and desolation have led to the same [peace] conference table where others could now join us at a much smaller cost.” On the same day he ordered the 1st Cavalry Division, Airmobile to Vietnam, with more units to follow. The United States was now fully committed.

*****

OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF DEFENSE 1777 NORTH KENT STREET ARLINGTON, VA 22209-2165 – June 17, 2012 – INFORMATION PAPER

Here is a different perspective of the timing – a paper written by a historian for the OSD Historical Office [references are cited at the end of the article]:

26 September 1945: Although some specify the (perhaps) accidental killing of Office of Strategic Services Lieutenant Colonel Peter Dewey on 26 September 1945 by Viet Minh soldiers as the start date, this is not accurate. Communist soldiers did indeed ambush and murder Dewey because they believed that he was French. Since the United States was not at that time a party to any conflict in Indochina, nothing of consequence resulted from this tragic event, and thus it is a nonstarter as a possible start date.

8 May 1950: For the first few years of the Indochina War between the French and the communist Viet Minh, which began in 1946, the United States took a hands-off attitude, regarding the conflict primarily as a colonial war. It was only in 1948–1949, as the Cold War got under way in Europe, that the United States began to re-interpret the nature of the war in Southeast Asia and see it as an anticommunist one. A related and compelling factor was that the United States needed French support and cooperation in Europe to contain the Soviet Union, and the price of that support was aid to the French in Indochina. By early 1950, the Truman administration was negotiating with the French government about how the United States could help in Indochina.

After inching toward the conclusion that the conflict in Indochina was part and parcel of the Cold War against communism and not a colonial war, the United States announced on 8 May that it was “according economic aid and military equipment to the associated states of Indochina and to France in order to assist them in restoring stability and permitting these states to pursue HISTORICAL OFFICE their peaceful and democratic development.”[1] This statement justified the provision of money and materiel to the French against the Vietnamese communists, the Viet Minh, for the following four years. By 1954, the year the French lost the war, America was paying almost 80 percent of the war’s cost.

17 September 1950: On this date, the United States established the Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), Indochina, in Saigon.[2] Its primary function was to manage American military aid to and through France to the Associated States of Indochina (Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia) to combat communist forces. Although the French took American money to support the war, they refused to allow the Americans much say in how the war was run or how the South Vietnamese military were advised and trained. The United States was not a principal in any sense of the word at this time.

1 November 1955: By the end of 1954, the French had lost the war, and an international conference in Geneva split Vietnam into a communist North and a noncommunist South. Cambodia and Laos also emerged as states as a result of the conference. The following year, 1955, France gave up its military advisory responsibilities in South Vietnam, and the United States assumed the job. To appropriately focus on its new role in Vietnam, the United States, on 1 November, redesignated MAAG, Indochina as MAAG, Vietnam and also created a MAAG, Cambodia. MAAG, Vietnam then became the main conduit for American military assistance to South Vietnam and, as well, the organization responsible for advising and training the South Vietnamese military. American influence experienced a substantial increase in the second half of the 1950s but not enough by any stretch of the imagination to argue that American was at war.

The establishment date of MAAG, Vietnam has great additional significance for those who wish to argue 1 November 1955 as the date on which the war began for the United States. The Department of Defense (DoD) decided in November 1998 to formally recognize 1 November 1955 as the earliest date on which a soldier’s death in Southeast Asia would qualify the soldier for inclusion on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. [3] According to supporters of this date, DoD’s decision implicitly recognized that the war had started for the United States on 1 November. However, this was essentially an administrative maneuver and not a statement that the United States in any substantive sense was at war. It should be kept in mind that President Dwight Eisenhower’s policy of advice and support was a limited one, and the number of military advisors never exceeded 1,000.

11 December 1961: In the second half of 1961, in the face of South Vietnam’s failure to defeat the Communist insurgency and the increasing possibility that the insurgency might succeed, President John Kennedy decided to substantially increase the level of U.S. military assistance to the beleaguered nation. National Security Action Memorandum 111, dated 22 November, stated that: “The U.S. Government is prepared to join the Viet-Nam Government in a sharply increased joint effort to avoid a further deterioration in the situation in South Viet Nam.” [4] This quickly translated into sending to South Vietnam the USNS Core with men and material aboard (33 Vertol H–21C Shawnee helicopters and 400 air and ground crewmen to operate and maintain them). The Core arrived in South Vietnam on 11 December and was the first of many such shipments. Less than two weeks later, the helicopters were providing combat support in an operation west-southwest of Saigon.

The heart of the argument for this date, and it is a strong one, is substantive: namely, that by sending helicopters, pilots, and maintenance personnel to Vietnam and allowing the helicopters to support South Vietnamese combat operations (for example, ferrying troops to the field and providing fire support as well as training the South Vietnamese for operations), President Kennedy had initiated the process through which the United States assumed a combat role. While it is clear that Kennedy had broken dramatically with Eisenhower’s limited policy of training, advice, and support, it is by no means generally accepted that this moment constituted the start date for America’s large-scale participation in the war. However, many have made a credible argument that this is America’s war start date.

7 August 1964: On 2 August 1964, North Vietnamese torpedo boats attacked the USS Maddox, a Navy destroyer on a signals intelligence mission, off the coast of North Vietnam. Two days later, a second attack on another destroyer on a similar mission supposedly took place (it is now accepted that the second attack did not occur). In the wake of these attacks, President Lyndon Johnson presented a resolution to Congress, which in turn voted overwhelmingly in favor of it on 7 August.[5] The key part of the Tonkin Gulf Resolution stated that “Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression.”[6]

Because of the robust and straightforward wording of the resolution, many then and later saw the Tonkin Gulf Resolution as the functional equivalent of a declaration of war. The Johnson administration certainly looked upon it as such. From this point it is not a huge leap to consider this date as a serious competitor for when the war started for the United States, despite the fact that little action flowed directly from it.

8 March 1965: As the situation deteriorated in South Vietnam and the United States ramped up its air war activities there, the Da Nang air base in northern South Vietnam became both significant to those activities and vulnerable to attack by Communist insurgents, the Viet Cong. To defend the air base, but specifically not to carry out offensive operations against the Viet Cong, President Johnson authorized the landing of the 9th Marine Expeditionary Brigade, about 5,000 strong, at Da Nang on 8 March. [7]

Although some see this date and action as a convenient start date, it is a hard argument to sustain. While it is true that the Marine mission around Da Nang evolved over time, the landing should best be seen as an important but not decisive interim step to President Johnson’s summer decisions to commit the nation to war, and to victory in that war. Meanwhile, Kennedy’s 1961 decision to send men and materiel had resulted, with President Johnson’s support after Kennedy’s death, in about 23,000 American military personnel in South Vietnam.

28 July 1965: Possibly the last point on the path to the full commitment of U.S. forces to the Vietnam War occurred in the late spring and summer of 1965. [8] By May, the situation had so deteriorated in South Vietnam that its military was losing the equivalent of a battalion a week. The U.S. Commander in Vietnam, General William C. Westmoreland, concluded that American combat troops had to enter the conflict as combatants, or else South Vietnam would collapse within six months. He made his famous 44 battalion request on 7 June, stating that “I see no course of action open to us except to reinforce our efforts in SVN [South Viet Nam] with additional U.S. or third country forces as rapidly as is practical during the critical weeks ahead. Additionally, studies must continue and plans developed to deploy even greater forces, if and when required, to attain our objectives or counter enemy initiatives.” [9]

This request became the vehicle for major discussions by Johnson and his senior policy advisors at the State Department, DoD, the National Security Council, and the Central Intelligence Agency over the next several weeks. In late July, Johnson made his decision and at a press conference on 28 July announced that “we are in Viet-Nam to fulfill one of the most solemn pledges of the American Nation. Three Presidents—President Eisenhower, President Kennedy, and your present President—over 11 years have committed themselves to help defend this small and valiant nation.” He then said that General Westmoreland had told him what he needed and that “we will meet his needs.” Later in the press conference, he said, “We will not surrender and we will not retreat.” Finally, to drive home America’s steadfastness, Johnson maintained, in a seldom-quoted part of his statement, that “we are going to continue to persist, if persist we must, until death and desolation have led to the same [peace] conference table where others could now join us at a much smaller cost.” [10] To put actions to his words he ordered that day the 1st Cavalry Division, Airmobile, and other units to Vietnam, with more to follow. The United States was at this point fully committed in an open-ended way to winning the war.

But did this press conference statement by President Johnson, which historian George Herring called “the closest thing to a formal decision for war in Vietnam,” [11] support the conclusion that 28 July 1965 was, all things considered, one of the better candidates for a start date? The short answer is “yes.” After this date the United States was, at least as long as Johnson remained President, irrevocably committed to fighting the Vietnam War to the end. Thus, 28 July 1965, though undoubtedly late in the game, is probably the strongest contender for the start date, if such a date has to be chosen. While historians know with certainty that the Duke of Wellington bested Napoleon at Waterloo on 18 June 1815, the Germans surrendered on the Western Front on 11 November 1918, and the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941, they must still live with ambiguity in offering answers to many complex historical questions. The question of when the Vietnam War started for the United States falls into that category of ambiguity.

It is impossible to state categorically that one date or another is the precise date on which the start of the war for the United States occurred. Put differently and emphatically: no obvious and verifiable start date exists. Probably the truest, though not the most satisfactory, statement to be made is that the process by which the United States became embroiled in the war was evolutionary and incremental. What can also be said, albeit with a little oversimplification, is that the United States acted in an advice-and-support role in relation to French forces (1950–1954) and later to the South Vietnamese (1955–1961). And starting in late 1961, the United States began a transition—at first slow but later more rapid—from advice and support to South Vietnamese operations to a direct combat role. By mid-1965, the direct combat role dominated and remained the major, but never the only (advice and support to the South Vietnamese military continued), role of U.S. forces in the Vietnam War until 1971.

If pushed to select a date with some traction, one might choose December 1961 or July 1965. The former represents a strong break with past policy and significantly led to the participation of U.S. military personnel in South Vietnamese operations primarily but not exclusively as tactical and intelligence advisers, as helicopter pilots to ferry troops to the battlefield, and as door gunners on helicopters. The latter represents the overwhelming commitment of the United States to winning the war and is an even greater break with the past. It represents the moment when the United States completed its transition from advice and support to direct military intervention. President Johnson and others often characterized the U.S. military goal as one of convincing the enemy that he could not win, but without a doubt this was only a less warlike way of saying the United States was in the war to win it, whatever winning might turn out to mean.

1 Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States (FRUS), 1950, vol. VI, 812.

2 Shelby Stanton, Vietnam Order of Battle (Washington, DC: U.S. News Books, 1981), 59. Others give this date as 27 September.

3 U.S. Department of Defense, Office of the Assistant Secretary of Defense (Public Affairs), News Release No. 581– 98, November 6, 1998, “Name of Technical Sergeant Richard B. Fitzgibbon to be Added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial.”

4 FRUS, 1961–1963, I, 656. For this policy story in documents, covering the period 15 October to 15 December 1961, see 380–738.

5 For a summary of the events surrounding the Tonkin Gulf incident and the subsequent resolution, see Lawrence S. Kaplan, Ronald D. Landa, and Edward J. Drea, The McNamara Ascendancy, 1961–1965 (Washington, DC: OSD Historical Office, 2006), 517–524.

6 The Pentagon Papers, Gravel ed., vol. 2 (New York: Beacon Press, 1971), 722.

7 Jack Shulimson and Maj. Charles M. Johnson, USMC, U.S. Marines in Vietnam: The Landing and the Buildup, 1965 (Washington, DC: History and Museums Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 1978), 16.

8 For the larger narrative of these weeks, see John Carland, Combat Operations: Stemming the Tide, May 1965 to October 1966 (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 2000), 45–49.

9 FRUS, 1964–1968, vol. II, 735.

10 Public Papers of the Presidents of the United States: Lyndon B. Johnson, Book II, 794, 795, 796.

11 Quoted in Carland, Stemming the Tide, 49

Prepared by: Dr. John Carland, Historian, OSD Historical Office, DA&M, (703) 588–2622

Approved by: Dr. Erin Mahan, OSD Chief Historian, DA&M, (703) 588–7876

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

I am curious as to why the 173d Airborne Brigade ( SEP ) is not mentioned as the first Combat Infantry unit to arrive in VN

LikeLike

When President Johnson went before the cameras on July 28, 1965 and ordered the US Army First Calvary Division AIRMOBILE to Vietnam, the Vietnam War began for me. That is when the US death toll for the US Army increased exponentially. It was 1965, and no other date, that qualifies as the one date the war began–why the confusion? I served there 31-months in-country, 1965-71 with the First Calvary, 23RD Infantry and 17TH Calvary of the 101ST Airborne Division units, always in US Army aviation units.

LikeLike

I thought it was informative..Filled in some of the blanks that were left for me back in the 50’s when we were just getting started in the fiasco with the French. And then of course spending 32 months participating in the South East Asia War games.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another point. The USS Turner Joy was the second destroyer in the Gulf of Tonkin incident. They said they were fired on, though “it is now accepted that the second attack did not occur” ? By whom, the guys thousands of miles away and after the fact?

I don’t know about you, but I’ll stick with the guys aboard the Turner Joy – they were there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a good chronological history of Vietnam but the author should have went back to Feb 1946. That is when Ho Chi Minh sent a telegram to President Truman requesting aid to rebuild Vietnam. Of course, Pres Truman stated no as France was going back to French IndoChina and France was our allie in WWII. Makes one wonder if Truman had told the frogs to take a hike and helped Ho, would we have had the death toll of that war. I bet France would have wished they would have stayed out of there, especially with Dien Bien Phu.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Actually, Truman opposed the French return to Viet Nam, forbade US shipping from supporting them by carrying cargo back there. But he was in no position to stop them. It was only much later when it became clear that Ho was a communist, very publicly devoted to Stalin, that the US began to support the French in their battle with the Viet Minh. Who were made up in part of nationalists (I know some personally who fought against the French, but late pulled away from Ho when his true agenda became obvious), whom were eliminated in the North after the Geneva Accords were signed. And it was Ho who invited the French back in shortly after the WW2 was over, to use them to wipe out the independent nationalists. Ho was a master manipulator, but he was always a communist, first and foremost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Ho Chi Minh, a Vietnamese nationalist who admired the works of Marx and wanted to establish a socialist state in his country”

The instant you see this sentence, you know someone is a total idiot. Ho was a lifelong devoted COMMUNIST, trained at the Lenin Institute in Russia, spent 25+ years as a Comintern agent in Asia before ever returning to Viet Nam. He did not “admire the works of Marx” so much as he admired and was devoted to Leninist principles and practice. He did not set up an enlightened socialist government, he set up a communist government with all the oppressive mechanisms of communist controls, which are still in operation to this day.

To see this complete crap on the government website is a horrendous shock.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Makes one wonder who is running the Commemoration site – obviously not any Vietnam veterans! Of course, they don’t answer any inquiries or comments, either. This is another example of how their ignorance is showing.

Our own military has no idea what really happened in Vietnam. Just think of all the students who look at their site, thinking it is all true.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s interesting, when I came here I’m so awakened I was cautioning myself this could be BS or am I going to get the straight info.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And?

On Wed, Jan 19, 2022, 10:13 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

>

LikeLiked by 1 person