My guest blogger, TJ McGinley, has contributed a couple earlier articles about his time in Tiger Force Recon, 1/327/101st Abn. Div., Vietnam 1968-69. Today, Mr. McGinley shares some thoughts and opinions about his humping days in the jungle – almost fifty years ago.

His story:

Our area of operation was a very narrow portion of the northern jungle covered mountains of South Vietnam. This gave the NVA a distanced advantage in that all they needed to do to avoid us was to head west over the ridge that ran north to south along the western edge of the AShau Valley – the other side was Laos where they knew we couldn’t follow. I never understood the concept of trying to sneak up on anybody in helicopters as they could be heard approaching miles away.

When I was in a line company, I didn’t realize how bad we were until I got into Tiger Force Recon. On company-sized operations, several choppers were used to transport troops into an area and normally required several lifts into the same LZ to get everybody on the ground. During each combat assault (CA), six to eight Americans jumped out of each ship and quickly disappeared into the jungle.

Every hilltop had NVA spotters whose job it was to let others know when Americans were in the vicinity. I can imagine the procedure: he’d be sitting on a hill eating his ration of rice when hearing a large number of helicopters approaching. The spotter watched them land in a row and counted the number of birds in the lift. He then hustled back to his unit and reported his observations to the officers in charge. His commander would then decide upon the appropriate action to take. I’d like to guess that he did the following: Inform nearby units and give them the tentative location(s) of the landing zone, and then send out additional recon units to look for signs of the Americans. If they were unsuccessful, commanders would want the patrols to return to base but to leave additional spotters within the area. If, on the other hand, a patrol was successful in locating the Americans, they’d note the route of travel and report back to their commanders. If the Americans weren’t headed toward anything significant, the commander might order his scouts to keep an eye on them and for them not to engage. However, if the Americans were headed toward their base camp, they might order hasty ambushes on the approach, and for everyone else to man the bunkers in defense of their camp.

If the NVA needed to buy some extra time, they’d use a tactic that worked every time: snipe at the soldiers and wound a couple bad enough to warrant a Medevac helicopter. In order for the Americans to evacuate someone, Medevac’s required a field large enough to land a chopper, and if there wasn’t one nearby, they’d have to blast a big enough hole in the jungle or risk a jungle penetrator to get the injured soldiers to hospitals. This entire process could take up to an hour, which allowed the NVA plenty of time to consider their next play.

Now, if they weren’t in a fighting mood or outnumbered, the commander might order his men into the underground tunnel complexes which were spread all over South Vietnam, and stay hidden until the Americans left. As a last resort, they’d pack up and cross over the border into Laos, where they knew the American’s wouldn’t follow. There, they’d wait until the choppers returned and pulled the Americans out of the area. Afterward, the NVA returned to their base camp and picked up where they left off. Not crossing the border was one of the big parodies of why Americans could never end this war.

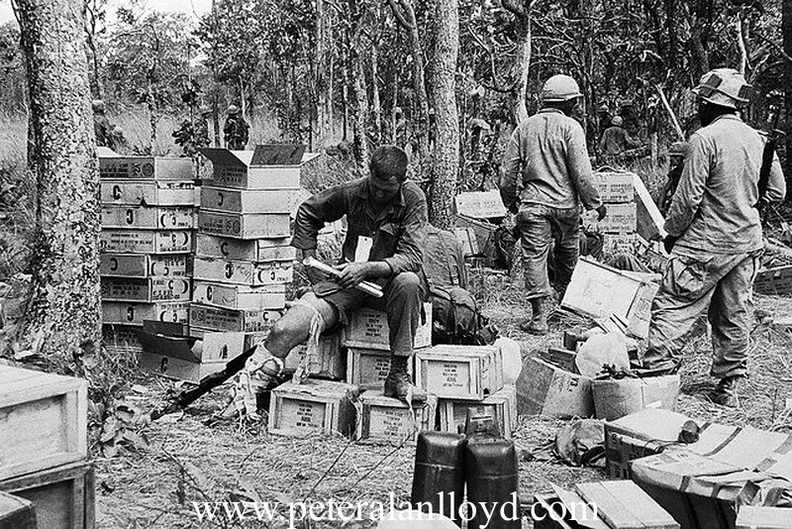

At first, I thought staying in the jungle for three months at a time were meant to keep our presence a secret. But there was a fallacy with that kind of thinking, too. When company sized troops operated in the bush, their re-supply every three to five days was usually an all-day process.

During a company-sized re-supply for 180 men, the distribution of food, clothes, ammo, sundries, and most important, mail from home took a while; their location, known for miles around. I remember that we would sometime blast a hole in the jungle – preferably on a mountain top, to enable as many helicopters as were needed to bring in the supplies. The size of the perimeter around the opening varied and was dependent upon the size of the unit; two and three man positions were strategically placed around the circumference, taking turns, two men remained on guard while the third secured individual supplies, cleaned-up, wrote letters or napped for a bit. Sometime, cooks brought out Thermite cans of food and served us hot meals and ice-cold Kool-Aid. A water bladder was also left on the LZ during the dry season for everyone to fill canteens. All through this process, a pair of Cobra gunships loitered nearby to protect the helicopters coming/going. I remember looking up once and saw a Cobra gunship overhead for the first time. I stood in awe while looking up at the belly of this stationary helicopter; I guessed it to be about 20 feet long and 5 feet wide. Short wings extended from the sides and I could see rocket pods attached beneath them, straddling a Gatling gun that poked out from within a painted mouth full of razor sharp teeth spanning the nose of the aircraft. It was a flying shark – poised to chomp on its next meal – far more deadly than any fish alive and it was hoped that it brought fear to the enemy. A few hours later, choppers arrived to pick-up leftover food and ammunition, a filled mail bag, an empty water bladder and thermite cans, and those soldiers needing to return to base.

The NVA had developed tactics to use against our jets and artillery, but a Cobra gunship could hover and fire 40 mm cannons, rockets and mini-guns, and just rain steel on any location they wished. Its best asset was the ability to change direction and assign targets in the air just as fast as a grunt in a firefight.

The smaller Tiger Recon teams of 6 – 12 men (my unit) would be inserted into Injun country using three choppers – the pilots performing some razzle dazzle maneuvers to get the team on the ground. They’d fly into an LZ, lift up and repeat the process 3-4 more times, inconspicuously inserting the team during one of the five touchdowns. Spotters weren’t able to see the birds on the ground and didn’t know on which LZ the team unloaded and how many soldiers were involved. When unloading on the ground, recon troops moved quickly into the surrounding jungle and then waited ten minutes or so to ensure there was no enemy presence. If we were ambushed, we could request an emergency pick-up on the same or at an alternate LZ. If the coast was clear, we continued with our mission – the NVA not knowing our whereabouts. Our resupply was also much different as we used only one chopper and at times, had our supplies dropped during a fly over. Either way, we were on the move again in just a few minutes.

Even counting choppers, the NVA couldn’t quite figure out how many Americans were on the ground and where we were located, thus posing a greater threat to them. Line companies were easy to track as one hundred sixty men walking through a dense jungle made a lot of noise.

Once, my mentor, John was on point, and I followed closely behind as his slack man, and realized that we had walked right into the corner of a good size NVA base camp. John raised his fist and motioned for the team to back up slowly and quietly. We must have snuck right past their security and into their camp. There were about 30 or more NVA soldiers milling around eating, cleaning weapons, and so on, and had absolutely no idea we were there. On our way out we located two sleeping sentries and dispatched them quietly, then moved a couple of clicks away from the camp and called in an artillery strike on that location. In a situation like this, a small, well-camouflaged unit of seasoned veterans could escape detection.

The rain forest was magnificent and maybe that’s why I was able to keep my sanity. We spent most of our time exploring places where most humans hadn’t been before. Everything was green and all encompassing, wet, and streams of running water was the cleanest you’d ever drink; the thick overhead canopy of leaves seemed to filter rainwater that seeped through and was captured in our canteen cups or helmet.

When in the jungle, you became a part of it. We were always wet either from the streams we just waded through, sweat, or monsoon rains. The rain was quite noisy and covered our movements, but also provided the same courtesy to roving NVA patrols. When we crossed a shallow river we rinsed off everything, hair, body and clothes to maintain our organic smell. The Vietnamese were masters at using this environment to conceal themselves. You could be staring to your front and not even see a bunker position five foot away; it was always a relief to find nobody home.

In the field, officers and super stripers didn’t mess with us. We didn’t need to shine anything, make a bed, shave, get haircuts or salute. We all knew who was in charge, and with everyone armed and dangerous, there was a mutual respect between the men – a respect that you didn’t find anywhere else in the military.

In 1863 Gen.William Tecumseh Sherman wrote, “war is long periods of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror.” Well he was right about the sheer terror, but we were never bored in the jungle. There was always something fascinating to discover. The trees didn’t start overlapping branches until they were about 80 feet tall, then after 100 feet, the upper canopy was a weave of branches that shaded the jungle floor for most of the day. We could sense a sun shining above, but rarely saw it unless we were on a hilltop above the canopy.

At night, the blackness was so complete you couldn’t see your hand two inches from your face. There were some plants, its leaves were streaked with phosphorous and glowed in the dark. More often than not, we used them to make a trail from our sleeping position to the guard position. I’ve seen spider webs as big as a bathroom wall covered with the morning dew, and once ran into a snake that was as round as a basketball. We couldn’t see the head or tail so we just stepped over it and left it alone. There weren’t as many animals as you might think in this environment and think the war scared most of them off.

One night we heard something in front of our guard position and readied ourselves for a fight. A trip flare soon ignited and we saw a large tiger spooked by the suddenness of light; it jumped ten feet into the air then landed with a large crash. It growled, and then took off running through the vegetation. I don’t think tigers and trip flares make a good combination. Nevertheless, our position was compromised and we had to move to a new location to evade any possible enemy patrol who might be dispatched to investigate.

I never realized how dangerous it was to be walking point for a line company until after joining Tiger Force. I recall stopping once on a hillside and sitting in perfect silence when on a combined mission. We listened as the long line of soldiers moved through the jungle, machete’s echoed loudly as point men created paths, soldiers whispered or bitched about the hump, the squelch of PRC-25 radios sounding like a television in between channels grew louder then quieter as the soldier moved past – repeating itself when the next squad approached, and the sound of an occasional M-16 hitting a rock or tree trunk when a soldier fell – it makes a very distinct sound that could be heard for miles. From overhead, we could tell in which direction they were headed, how fast they were moving, and could estimate how many soldiers were involved; one-hundred eighty soldiers or even a platoon of forty working through the dense jungles of the Central Highlands was just too many to maintain noise discipline and be effective against the NVA and the tactics they used.

I grew up a suburbanite, living in a nice neighborhood in Kansas City, Missouri. I was in the Boy Scouts and really enjoyed camping in the woods of southern Missouri. I remember joining a dozen new guys on April 28, 1968, six members of Tigers Force led us through the jungle of the Central Highlands and rendezvoused with our parent company. I stayed in that jungle until we were extracted from the southern end of the AShau Valley on June 29th, 1968, then enjoyed five days of eating real food, taking real showers, and getting real sleep. At the end of those five days, we were sent back out to the same jungle for another three months. I’m thankful for the Tiger Force training and discipline – it allowed me to be a ghost in the jungle and survive the war.

Thank you TJ for another fine article. Thank you, too, for your service, sacrifice, and welcome home! Here is the direct link to TJ’s other contributions to this blog:

https://cherrieswriter.com/2015/10/15/ghost-warriors-guest-blog-2/

https://cherrieswriter.com/2015/12/10/inappropriate-behaviour-and-punishment-in-the-nam

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

Did you know my uncle, Louie Kimbrell? He was from Sibley, Mo. He served from November 1967 till June 28, 1968. He was KIA. I appreciate any information you might know. Louie was my dad, Joseph (Abe) Kimbrell’s brother. As a child we never talked about what happened to my Uncle Louie. I just turned 40 this year and with age, my desire to research, learn and find anything that could be out there about my Uncle from articles, photos or even videos is a priority and I cant put into words how important it is to me.

Thank you,

Julie Kimbrell-Pollard

LikeLike

Great article(s) by McGinley.

Is there a way to get in touch with him, asking some questions (or that you fwd my mail)?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Jay, I just sent him an email asking how he’d like to proceed.

LikeLike

Great argument for a professional Army. Also we all know the brain dead Washington politicians FUBAR’d that war.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article and well written. Kind of hard to control the noise factor when a platoon or more are tromping thru the bush. A squad is much better. Insertion could always be a problem. Nothing like advertising what a unit is going to do.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree with almost every thing said in the article. ..I was Echo Co, Recon, 3/12/4 Div in 69/70. We were in the Ashau Valley the last few months. I hated that place.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Welcome home! God Bless.

LikeLiked by 1 person