How many casualties occurred because of friendly fire during the Vietnam war?

Nobody knows for sure. No one was keeping count, not all incidents were reported or even recognized as friendly fire, and the military did not want this to get out. Friendly fire is an attack by a military force on non-enemy, own, allied or neutral, forces while attempting to attack the enemy, either by misidentifying the target as hostile, or due to errors or inaccuracy.

It’s estimated that there may be as many as 8,000 friendly fire incidents in the Vietnam War caused by mistakes, negligence, exhaustion, panic, horseplay, dim lighting, dense vegetation, inattentiveness, faulty equipment, poor training, foolishness, ill fortune or some combination of the above. There doesn’t appear to be any agreement of a firm percentage attributed to FF during the war, I’ve seen estimates ranging from 2.4% – 39% of all combined casualties. How were individuals categorized? The military refers to Friendly Fire as “misadventure” – correct me if I’m wrong, but I think this is the worst use of words, ever.

How does one differentiate the difference on the battle field? Are autopsies performed and fragments / bullets removed and identified? In the annals of warfare, deaths at the hand of the enemy are often valorized, while those at the hand of friendly forces may be cast in shame. Moreover, because public relations and morale are important, especially in modern warfare, the military may be inclined to under-report incidents of friendly-fire, especially when in charge of both investigations and press releases: is the tendency by military commanders to sweep such tragedies under the rug? It’s part of a larger pattern: the temptation among generals and politicians to control how the press portrays their military campaigns, which all too often leads them to misrepresent the truth in order to bolster public support for the war of the moment. The death of a soldier from friendly fire has been described as “. . . the most ghastly type of casualty you can anticipate.” The emotional impact of friendly fire casualties may be more destructive to a unit’s morale and fighting capacity than enemy fire. Each incident can cause a gradual degradation of combat power by lowering morale and confidence in supporting arms, a factor so vital to combined arms operations.

Here’s a list of potential causes of Friendly Fire:

- Use of the term “friendly” in a military context for allied personnel or materiel dates from the First World War, often for shells falling short; errors of position occur when fire aimed at enemy forces may accidentally end up hitting one’s own.

- Errors of identification happen when friendly troops, neutral forces or civilians are mistakenly attacked in the belief that they are the enemy.

- Difficult terrain and visibility were major factors. Soldiers fighting on unfamiliar ground can become disoriented more easily than on familiar terrain. The direction from which enemy fire comes may not be easy to identify, and poor weather conditions and combat stress may add to the confusion, especially if fire is exchanged. Accurate navigation and fire discipline are vital. In high-risk situations, leaders need to ensure units are properly informed of the location of friendly units and must issue clear, unambiguous orders, but they must also react correctly to responses from soldiers who are capable of using their own judgement.

- Miscommunication can be deadly. Radios, field telephones, and signaling systems can be used to address the problem, but when these systems are used to co-ordinate multiple forces such as ground troops and aircraft, their breakdown can dramatically increase the risk of friendly fire. When allied troops are operating the situation is even more complex, especially with language barriers to overcome.

Here are some examples of recorded incidents:

19 November 1967, a U.S. Marine Corps. F4 Phantom aircraft dropped a 500 lb (230 kg) bomb on the command post of the 2nd Battalion (Airborne) 503d Infantry, 173d Airborne Brigade while they were in heavy contact with a numerically superior NVA force. At least 45 paratroopers were killed and another 45 wounded. Also killed was the Battalion Chaplain Major Charles J. Watters, who was subsequently awarded the Medal of Honor.

16 March 1968 at FB Birmingham Marine F-4s dropped bombs on the base killing 16 and wounding 48 men of the 101st Airborne.

18 March 1968, around 10 Marines were killed by MACV-SOG operators mistaking them for enemy forces, when such operators were trying to ambush the supposed enemies. The incident was result of stress and a bad intel, as their commander said that the area was in enemy control.

5 February 1969, Sgt. Tony Lee Griffith, of H Co. 75th Infantry (Ranger), led his five-man long-range reconnaissance team through thick fog and dense, short brush between An Loc and the Cambodian border. Hearing wood being chopped not far off a trail they were assigned to surveil, he had his team set an ambush. But members of the North Vietnamese Army had also detected the team. At dawn several enemy soldiers stole through the fog and flung a grenade into the middle of the team, who were spread along the trail, in sight of each other. The grenade exploded next to the front scout, Cpl. Richard E. Wilkie, showering him with shrapnel. As the enemy opened fire, the two team members on Wilkie’s left panicked and fired in the direction of the grenade’s blast. Caught in an intense crossfire, Wilkie, a Special Forces veteran, was shot five times––once by the enemy, twice by his team, and twice by bullets that passed through him. Miraculously, he survived. So, too, did the assistant team leader, Lewis D. Davidson, who was hit twice in the leg. Tony Griffith’s luck, however, ended that morning, when he was hit by multiple gunshots to the chest.

11 May 1969, during the Battle of Hamburger Hill, Lt. Col. Weldon Honeycutt directed helicopter gunships, from an Aerial Rocket Artillery (ARA) battery, to support an infantry assault. In the heavy jungle, the helicopters mistook the command post of the 3/187th battalion for a Vietnamese unit and attacked, killing two and wounding thirty-five, including Honeycutt. This incident disrupted battalion command and control and forced 3/187th to withdraw into night defensive positions.

1 May 1970, on military operations in Phước Tuy Province a burst of machine gun fire followed by a calls for the Medic split the night, an Australian machine gunner opened fire on soldiers of the 8th Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment without warning, killing two and wounded two other soldiers.

20 July 1970, patrol units of ‘D’ Company 8th Battalion, 1st Australian Task Force outside the wire at Nui Dat called in a New Zealand battery fire mission as part of a training exercise. However, there was confusion at the gun position about the fire corrections issued by the inexperienced Australian officer with the patrol. The result was two rounds fell upon the patrol, killing two and wounding several others.

24 July 1970, New Zealand artillery guns accidentally shelled an Australian platoon, 1 Australian Reinforcement Unit, (1 ARU), killing two and wounding another four soldiers.

10 May 1972, a VPAF MiG-21 was shot down in error by a North Vietnamese surface-to-air missile near Tuyen Quang, killing a pilot.

2 June 1972, a VPAF MiG-19 was shot down in error by a North Vietnamese surface-to-air missile near Kep Province, killing a pilot.

24 December 1970, Co. A 1/327, 101st airborne infantry on when Artillery was misdirected by the officer platoon leader and 2 High Explosive artillery rounds landed in the NDP of 2nd platoon killing 12 and leaving the remaining members of the platoon in the jungle all night without support until the next day when the rest of the company could get to them to clean up the mess.

October 1970, my platoon was involved in a friendly fire incident. We had a new lieutenant while out on a mission and prior to setting up for the night, he requested a spotter round to burst roughly 250 meters away to confirm the location of our NDP. However, when picking the coordinates, he did not take into account the gun trajectory path from the firebase and the coordinates he chose were in the air between our position and the guns. His spotter round confirmed the coordinates and then, everyone heard the spent canister approaching – whoop, whoop, whoop as the empty tube continued on its trajectory. We only had seconds to find cover. The canister landed just outside of our perimeter, bounced and then summersaulted across our NDP like a runaway wagon wheel. It stopped suddenly after crashing into a 2-man position and severely wounding the two surprised soldiers.

The movie about Ron Kovak Born on the 4th of July depicted him being shot in the back by a member of his own platoon while reconnoitering in front of the perimeter. He survived, but was paralyzed for life.

The movie, ‘We were soldiers’ showed an incident when napalm was dropped on US lines and killed several American soldiers.

- This incident occurred while a US infantry company was establishing a night defensive perimeter. In firing their planned defensive fires outside of the perimeter, the initial 81mm mortar round fell short and only traveled 35 meters from the tube, wounding three US soldiers (one later died of wounds). The platoon sergeant, located in an adjacent gun pit, saw the round flutter and drop. He immediately yelled, “Short round”, but the enlisted man who died of wounds started running rather than taking cover

- Following this incident and after troops were cleared from the immediate area, an additional round was fired using the same data and ammunition lot number. This second round functioned normally and landed in the planned impact area.

- The cause of this incident was attributed to ammunition malfunction and not human error on the part of the gun crew.

- A US infantry platoon conducted a mounted combat patrol and established an ambush position in the vicinity of a district headquarters compound. During the evening, US troops engaged an enemy force. A Light Fire Team (LFT) was requested and within a few minutes arrived on station. The sub-sector advisor directed the LFT commander to engage the wood line north and west of the compound. On the first firing pass, the LFT’s fires impacted in the vicinity of the friendly troops. The battalion commander requested that fire be shifted to the west. The LFT was informed but almost immediately the battalion commander reported that the gunships had again fired on the US troops. The advisor gave a cease fire and released the LFT. This incident resulted in the death of one US soldier and injury to nine others.

- The primary cause of this incident was the employment of a LFT too close to friendly troops at night without clearance from or communications with the ground commander. The primary factor contributing to the incident was a misunderstanding between the subsector advisor and the LFT as to the exact location of friendly troops. The advisor failed to give specific coordinates of friendly troop dispositions and US military units in the immediate area were not monitoring the advisor’s net which controlled the LFT.

- This incident occurred when a Forward Observer (FO) with an infantry company requested a 100 meter shift away from a previously fired Defensive Concentration (DEFCON). The DEFCON had been fired during darkness, in thick growth, and apparently was much closer to the battalion’s perimeter than estimated. The observer’s target description misrepresented the criticality of the situation and caused the Fire Direction Center (FDC) to fire the DEFCON as a contact mission not requiring safe fire adjustment of the battery. This action resulted in the death of three US soldiers and injury to nineteen others.

- Causes of this incident were a misrepresentation of the nature of the target in a fire mission and failure to comply with established policies for the conduct of non-contact missions close to friendly perimeters.

- This Incident occurred when a 105mm artillery battery fired an unobserved “trail runner” mission. When fired, due to a misunderstanding on area clearance, six rounds impacted in the proximity of friendly personnel resulting in the injury of one ARVN soldier and three Vietnamese civilians. The mission was passed from one artillery battalion to another due to a boundary change in two brigade Areas of Operations (A0s). When questioned, the original firing battalion Fire Direction Officer (FDO) indicated that the areas to be fired were cleared. The FDO of the receiving battery then assumed that all required area clearances had been obtained but in reality targets had been cleared only within the AO of the old firing battalion. All gunnery data and procedures were found to be correct.

- This incident was caused by the failure to clarify exactly what clearance had been obtained and the statement that the areas were cleared should have been amplified as had been the practice on previous occasions to indicate what clearances had been granted.

- One tube of a 4.2 inch mortar platoon fired with a 200 mil discrepancy in deflection while firing a registering round in support of the defense of a battalion perimeter. One round impacted in a company sector and four US soldiers were killed and ten wounded.

- The cause of this incident was determined to be a failure on the part of the gunner to refer his sight as directed and was compounded by the failure of the squad leader to make the required safety checks.

- This incident occurred while a US squad was conducting patrol activities in the vicinity of a fire support base. The squad leader saw a Viet Cong with a weapon and decided to call for artillery support. He sent his fire command to the artillery reconnaissance sergeant on the company internal radio net. The reconnaissance sergeant determined that the range to the target was 350 meters, verified this with the observer and inserted ‘Danger Close, 250 meters’ into the fire request. This was transmitted to the artillery liaison section in the infantry battalion Tactical Operations Centre (TOC), cleared, sent to the supporting artillery battalion and further assigned to a firing battery who processed the fire command and a smoke round was fired. This round was spotted in a rice paddy about 300 meters to the right flank of the observer, who then adjusted with ‘Left 150, repeat smoke’. This second round impacted again to the right flank of the observer who then erroneously repeated ‘Left 150’. The reconnaissance sergeant, monitoring the mission, asked the observer if he desired Shell, HE, Fuze Quick. The observer replied that he did and was warned to get his troops down because of the close proximity of the adjustments. The round was fired and impacted in the vicinity of the squad, injuring three personnel.

- The squad leader became disoriented during the adjustment of the mission. He unconsciously faced the second round as it impacted, estimated the distance to the target as being 150 meters, and gave a correction of ‘Left 150’ instead of ‘Add 150’. The FDC had no way of knowing that the observer had changed his Observer – Target (OT) azimuth by 1600 mils and accepted the “Left 150’ as the desired shift. The cause of this incident was the incorrect adjustment of artillery fire by an inexperienced observer.

- This firing incident resulted from a change of coordinates during clearance for fire procedures between the operations center of an artillery battalion and the TOC of the infantry division artillery. In the telephonic transmission of the fire request, the grid coordinates were transposed from XT6324 to XT6423. This error resulted in one killed for the requesting infantry unit.

- The cause of this incident can be attributed to a lack of double check procedures on fire requests by each element in the clearance chain.

- The FO with an infantry battalion called the FDC of the supporting artillery battalion and gave target coordinates for an adjust fire mission and indicated a platoon or larger size enemy force. The mission was passed to a firing battery and was followed by the artillery battalion FDC. After adjustment had been completed, the FO called for fire for effect on the same target. Since the battery had only four guns available at the time, it was directed to fire a battery six rounds. Due to a breech-lock malfunction, the number four howitzer was called out of action and the number five howitzer was directed to fire three additional rounds in order to complete the fire mission. Shortly thereafter the FO with the infantry unit notified the artillery battalion FDC that several rounds had landed in the vicinity of the unit’s perimeter and that one gun appeared to be firing out of lay. This incident resulted in two US soldiers being wounded.

- The cause of this incident was attributed to a 100 mil deflection error by a howitzer section of the firing battery.

- A battery of US artillery fired fifteen 105mm rounds which detonated near a bridge being secured by US and Vietnamese Popular Force (PF) soldiers. This fire mission resulted in the wounding of one US and one PF soldier.

- The fire mission was called in by a PF soldier and relayed through the district chief and the US liaison representative at district headquarters. US target clearance was obtained from the appropriate US artillery battalion liaison officer who was unaware that a US armored personnel carrier was positioned at the bridge. The target was mis-plotted 1000 meters by the ARVN district chief and the observer target direction was also incorrectly given as 3200 mils instead of 320 degrees.

- The first round in adjustment was fired and the correction given was ‘Drop 300’. The second round was fired and a correction of ‘Right 300, Fire for effect’ was requested. At this time the firing battery FDO informed the Vietnamese that the “fire for effect” plot was within 200 meters of the bridge. The Vietnamese confirmed the request and the FDO then requested that personnel at the bridge be warned to take cover. A battery of three rounds was fired which resulted in the two casualties.

- The cause of this incident was the error in the determination of the target. The PF at the bridge either disregarded or did not receive the warning of the close proximity of the fire for effect rounds. As a result, the US personnel were not aware of the danger although they had observed the round adjustments prior to the fire for effect.

- A FO with a US infantry company was firing a destruction mission with one gun of the supporting artillery battalion on a well fortified B-40 rocket position 30 to 40 meters north of the company location. Adjustment was difficult due to terrain and proximity of the enemy rocket position to friendly forces. The FO had to adjust by sound and could only observe those rounds which became air bursts after hitting trees. The FO’s last correction, as sensed from the previous round, was correctly computed by the FDC, checked by the section chief and fired. Because of the uneven terrain and the probable error of the range fired (9,920 meters), the round impacted outside the company perimeter, resulting in the death of one and the injury to a second member of the infantry unit.

- The two personnel involved in this incident were outside the unit perimeter. This was a direct violation of the unit commander’s order that all personnel would stay under overhead cover until the fire mission was completed.

- Cause of this incident was a violation of orders to remain under protective overhead cover while artillery was being used for close-in support. A contributing factor was the proximity of friendly troops to the target.

- Friendly casualties were caused when an unknown number of 105mm rounds impacted on their position during a contact mission.

- Cause of this incident was that the mission was started by a ground FO, however, he was unable to observe the rounds. The mission was then taken over by an airborne observer who made shifts along the gun-target (GT) line, while the FDC was plotting the shift along the OT line.

13 January 1967, A Battery, 8th Battalion 6th Artillery apparently transposed the last two numbers of the coordinates and fired approximately 18 rounds that landed on A Company, 1st Battalion, 28th Infantry, 1st Infantry Division. Nine men were killed and more than 40 wounded. The units were taking part in Operation Cedar Falls in the Iron Triangle. It’s believed the battery commander was Capt. John Seely and the battalion commander was Lt. Col. Ben Safar.

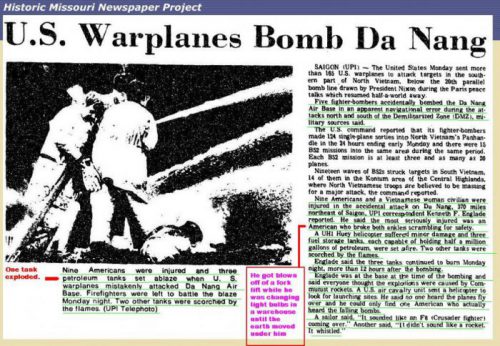

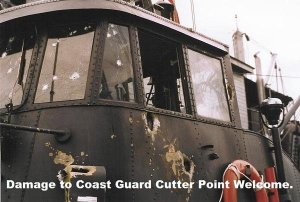

USCGC Point Welcome was attacked by USAF aircraft, with two deaths resulting.

17 June 1968, USS Boston, USS Edson, USCGC Point Dume, HMAS Hobart and two U.S. Swift Boats, PCF-12 and PCF-19 are attacked by US aircraft. Several sailors were killed and PCF-19 was sunk.

Even in todays war, the former NFL star, turned Army Ranger, Pat Tillman was shot by his own troops in Afghanistan…covered up at first. Why?

Did you know that when a soldier is wounded or killed by friendly fire or other accidental means did not qualify for a Purple Heart? Could this be one of the main reasons to cover up many other FF instances? NOTE: The law has recently been changed and PH medals are now awarded if the wounds caused by FF occurred while your unit was engaged with the enemy.

Nothing compares to the stress, confusion, and emotion of combat. People make decisions that are irreversible, and other people may die as a result. The death of a soldier is always tragic, but never more so than when he is inadvertently killed by his own comrades.

It’s a tragedy for any war but then the Vietnam war had it’s own unique form of friendly fire deaths. There were some who were killed intentionally by those individuals who would take things into their own hands. A 2nd Lt. fresh out of OCS might find himself with an M16 round in his back should he be deemed hazardous to his platoon or worse on the receiving end of a frag grenade. There are no statistics to show how many were killed on purpose but it happened. I can imagine and only hope that the ones responsible are eventually held responsible if by no one then their own conscience.

The second classification is “murder” where friendly fire incidents are premeditated. During the Vietnam War, some officers who overtly risked the lives of their soldiers were murdered by those men in incidents known as “fragging.”

Here is some data compiled by William F. Abbott from figures obtained shortly after the construction of the Vietnam War Memorial:

Cause Of Casualty Hostile & Non-hostile (Percentage):

Gun shot or small arms fire —- 31.8

Drowning and burns ———- 3.0

Misadventure (Friendly fire) — 2.3

Vehicle crashes ———— 2.0

Multiple frag wounds grenades, mines, bombs, booby traps — 27.4

Aircraft crashes ———- 14.7

Illness, also malaria, hepatitis, heart attack, stroke — 1.6

Arty or rocket fire ——– 8.4

Suicide —————- 0.7

Accidental self-destruction, intentional homicide, accidental

homicide, other accidents. — 5.8

Other, unknown, not reported — 2.0

How many actual deaths by friendly fire were just lumped into one of the above categories based on the situation they were in?

The problem of friendly fire will never be completely eliminated because the “fog of war”, human error, and material failure inevitably will make some Instances of friendly fire impossible to avoid. Our duty is to take all reasonable measures to minimize its tragic occurrence.

Any VNVets out there ever witness a “Friendly Fire” incident?

*****

Information for this article was obtained from Wikipedia, , NY Times, vietvet.org, Defense Manpower Data Center

http://www.americanwarlibrary.com/ff/ffv.htm

https://www.globalsecurity.org/military/library/report/1992/WBG.htm

If anyone is interested in reading my earlier article about “Fragging” click here: https://wp.me/pRiEw-2Sf

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

On August 6th 1968, 33 Marines of 2nd Platoon, Fox Company, 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment, 1st Marine Division, took a direct hit up to 500 lb bombs of napalm buy a Marine F4 Phantom jet. Years later I came to find out from a reporter attached to our company, that a new Second Lieutenant platoon Commander called in our wrong coordinance. The pilot and the REO got confused instead of dropping their Ordnance a thousand over to our right where the white phosphorus smoke was they pulled the cord too soon. 26 Marines running around with melted skin and deep burns, one of them almost charcoal, from the 3,000 degree gasoline gel. Though I did not get the Napalm gel on myself I was closest to impact about 15 yards away the doctors tell me years later that the Bomb Blast wave destroyed much of my frontal lobe and temporal lobe brain functions. I had just turned 19 years old. Since that time my life has been very close to having dementia and it’s gotten a lot worse as the years have gone by. Two marines of the 26, died at the scene. I have a copy of the small notation from the company office Clerk. And that is it. I’m positive there’s a lot more including the deposition of the pilot in the REO. But I have no way of finding it. And of course it’s not in my records. However there is a chapter in a book, written by, at the time Captain David Brown and his daughter, called Battlelines. And why it’s not included in your list of Friendly Fire incidents, I have no clue. But I can say that life is been pure hell.

I welcome any comments you might have.

LikeLike

I LIKE YOUR ARTICLES ON FRIENDLY FIRE . I WAS IN 4TH ENG AT LZ ENGLISH 1969. I WAS FIRST ON SEEN OF A FRAGING . TO THIS DAY I CAN NOT FIND ANY INFO ON THIS INCIDENT. I SURE WOULD LIKE TO KNOW WHY, I HAVE ALLOT OF QUESTIONS , LIKE WHERE WERE THE MP’S. THEY GAVE ME A 45 CAL . AND HAD ME TAKE THE TWO MEN IN TO BASE CAMP. LARRY

LikeLike

Yes, he would be included on the VVM.

LikeLike

This is all most helpful. I’m a novelist needing help on a specific detail. I assume a soldier who was killed in “friendly fire” would still be listed on the Vietnam War Memorial? Thank you.

LikeLike

I was a machine gunner with kilo 3/7 first Marines on april 1969 deep in the jungle in central viet nam. Two phantoms came in to give us air support during a fire fight and dropped two 5oo lb bomb directly on top of us. They wiped out half of my company. I still hear the screams of my wounded brothers in my nightmares. I can find no record of this anywhere, Imagine that. fuck politicians

LikeLike

FBI Files: George H. W. Bush’s Top Secret CIA Drug Running Empire

declass

http://impiousdigest.com/operation-eagle-ii-the-top-secret-cia-drug-running-empire-and-george-h-w-bush/

LikeLike

For pdoggbiker, or anyone else who can answer. I would like to know the following:

1) When the coordinates for an enemy assault by air are made who sends out the coordinates? Does the radioman send out the coordinates or does the officer in charge of a platoon (a lieutenant, for example) send them out himself?

2) Are the coordinates which are sent out calculated by the officer in charge of, say, a platoon or by the radioman? Would an officer double-check all calculations done by a radioman if the radioman makes the calculations?

3) In other words, if an error in coordinates is sent out, who is responsible–the radioman or the officer in charge of a platoon?

4) Who actually reads out the coordinates on the radio–the radioman or the officer?

Thanks for any help you might offer. This is a very informative site.

Andrew

LikeLike

On August 4th, 1968, noontime Fox Company is moving out after all night firefight. Fox company, 2nd ,Battalion 5th Marines, (2nd platoon), Providing rear support for the company commander and headquarters platoon.I was the last man in the company column, called taking up the rear. All of the sudden, I spot an F4 Marine Phantom Jet, just into his 1st pass around our coordinance. On the pilot’s 2nd pass, I remember thinking saying to myself someone is going to get it. Than the F4 began its dive right down on top of my platoon. I yelled to everyone ahead of me, than jumpped to the ground, my helmont fell off. The next thing I knew I was looking up above my head at a gigantic mushroom ball of fire. Everything was surreal. I never heard the sound of the bombs exploding, though I was closest to the impact of the 500 pound canisters of Napalm. ( The ccnnasters tumble down and upon impact the exploding gasoline gel, burning at 3,000 degrees, flows forward). I was just out of reach from the napalm itself but incurred Traumatic Brain Injury. I had just turned 19. I then I looked forward and saw what I now know was 26 of my platoon’s fellow Marine brothers on fire, skin melting off. I helped a Corpsman, who was desperately trying to comfort one of my buddies. The corpsman asked me to remove the Marine’s boots. I began pulling off his boots and all of his melted skin came off, down to the bone. He was a Corporal who had just finished lunch and he died 20 minutes later.

LikeLike

Sir, during the Vietnam War, how close to friendly troops could precision bombing from friendly aircraft land rounds (aimed at the enemy) without harming friendly troops? In other words, 150 meters, 200 meters, etc.?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Andrew,

Mistakes were made on the ground and in the air when it came to determining proper locations. We didn’t have GPS, laser guided bombs, and sometimes, ordinance fell on your position or extremely close enough to cause injury when expectations were to have them land 300 meters away. On the other hand, most of the time, ordinance was dropped where it was expected and saved a lot of American lives. You should also know that pilots see things from the air that are not known on the ground and their input also helped us in that regard.

On Sun, Jun 3, 2018 at 11:58 AM, Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLike

Dear John, Thanks very much for your comments. They’re very helpful. I’ve ordered your novel “Cherries” from Amazon.com. I see that you have another one there, too. “Cherries” should arrive soon. Thanks again,Andrew

LikeLiked by 1 person

Than you, Andrew! I hope you enjoy and learn from my story! Would love to see your review on Amazon when done!

LikeLike

ûTttgtttttggm

Sent from Yahoo Mail for iPhone

LikeLike

Made me Think about 1-10-68; Later years, Date, was noted by one of the remaining men from Alpha Company.

1/27th Wolfhounds of the 25th infantry division hit a NVA camp, best to my recollection, in the Iron Triangle. As a infantry FO for 81 mortars, C47, I was with the second platoon of C company. Have no recollection of where Bravo and Delta companies were, but know as a Battalion site was being secured for weapons platoons and Headquarters’ company, one company would probably have been assigned to secure a perimeter.

Charlie and Alpha company were headed in toward a Wooded Area. Charlie company was exposed moving forward when fire-fight started. Third platoon was the breast, leading, but the whole company came under fire. Throughout the action, observable losses became apparent.

Recall listening to a Dust-off Pilot asking us how secure our LZ was for removing KIAs and WIAs, since he was on his fourth bird that day.

Throughout the action, could see A-1 Prop Skyraiders dropping bombs, which were dropped off Charlie Company’s left Flank. Alpha company to our left, heard and saw dropped Napalm. Heard later, being flown by ARVN Pilots. Planes missed target, Napalm dropped short, pretty much decimating Alpha company. Few that survived were burned from Napalm.

Choppers, came In dropping smoke As C company pulled back, regrouped, further Air support came in, and later Artillery.

Later, Was told to look at my radio antenna Was shot off, with only the base of it remaining.

Know C48, the third platoon FO, had been hit along with maybe C44 of the first platoon. Looking at our remaining men From C company, didn’t think, at the most, it was any more men than what’s in a platoon.

Hearing we were going to go back in Went to the CO and told him where I could possibly set-up to call in fire. Was told “ NO, I want to keep you alive”

With some reinforcements, we were heading back in, along with the hopes of saving a soldier that hadn’t been removed, no one had seen him get hit, and we were informed, he was just sitting there on our field of action. Certainly, possible bait for us!

As we Went back in with Artillery support, Artillery Frag was landing around us. As I took a picture of us heading to go back in , men kneeling were probably praying as well as staying lower from the Frag, myself included.

Moving forward, Frag was hitting by us, knowing some larger pieces the size of a golf ball could have taken anyone out.

Went In the second time with Two Armored Dusters, and recall telling guys to give them room, “don’t get too close, rounds will be ricocheting off those dusters.” Second Platoon’s Sergeant Leifer, and I would tell any new replacement, that when we move, move with us, might give them a kick going by, letting them know, and telling them we’re moving. Wasn’t going to stop to get them up, knowing the instant we stopped, we’d be dead.

During that second time in, we could see units unloading from Eagle flights off to our corner right. Later, heard they were units from the 101st and Big Red One.

Actually, Didn’t care what units they were from, was just glad to see other units for the support, and coming in to help with the fight.

Coming back out, saw where my radio antenna was once again shot off by the base, battery was hit, and was asked what happened to My Helmet. Removing, could see the camo- covering was shredded. So be it, made it out !

Second day, we reworked the AO and saw area where Alpha company hit was around what would have been the NVAs command bunker. Found tunnels, but trying to flood them didn’t work.

Later, heard Sp4 Bob Comstock, C48,which had been wounded, was awarded Silver Star for his action in helping get WIAs out

A hit Medic, of one of the platoons, Sorry I forget the name, which continually gave wounded troops aid, was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.

DSC was also awarded to a platoon leader, with multiple wounds, remaining.

Perhaps, you’ll hear more from those Wolfhounds that survived that day.

Morning Reports from the those days might recall and report of the contact.

As reports are filed for all those KiAS and wounded, they may present a better report!

Respectfully,

Former Charly 47

Sergeant Sielaff

Co C, 1/27th Wolfhounds

LikeLike

Thank you fellow hound!

On Fri, Apr 13, 2018, 10:20 AM Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLike

I didn’t get one but 2 motor pool Marines got one and I have proof

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

Does friendly fire constitute a Purple Heart in a in country combat zone?

Sent from my iPhone

LikeLike

James, the answer is yes providing the FF occurred while targeting the enemy

On Thu, Apr 12, 2018, 1:30 PM Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLiked by 1 person

Interesting. When the ammo dump exploded in 71 in CamRang Bay, I was stationed at 22nd Replacement Bn, several miles from main Cam Ranh. I heard that one of the drug addicted patients left the 6th CC hospital, several miles away from our compound and wounded by one of our soldiers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Far too many incidents listed above. Our battalion compound in Camp Eagle, the HQ of the 101st Airborne, got hit one sunny and clear afternoon in 1971 by 3 howitzer rounds. They came in out of the blue. Came close but no injuries. I never found out what happened– too low on the totem pole but there was absolutely no reason to be firing in our direction – all the NVA were west of us in the mountains.

I remember the incident where friendly fire was called into a NDP outside of Camp Eagle on Christmas Eve 1970, killing 12. Shows the importance of reading a map and having experienced personnel plotting fire. Just think – the families of those 12 are scarred for lift – every Christmas they face the anniversary of the death of their sons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great articles. How many incidents happened that were not reported. Several years ago, there was a book that came out “Friendly Fire.” It is about parents seeking information and redress from the government. We know how that goes!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I saw the movie “Friendly Fire” in 1979 and didn’t realize until half way thru it that it was based on an incident which happened to my unit. Charlie company, 1/6 inf, 198 LIB, Americal Division was hit by H&I fire at 2 AM while in a mountain NDP. 2nd Platoon (my platoon) was on the other side of the perimeter from the air burst (round hit a 200ft tree). I remember having to cut down trees with machetes to get the medivacs in. Was not a good night. We figured it was either an Arty error or the FO we had with us didn’t take into account the 200 ft trees on that side of the perimeter. Still don’t know to this day was actually happened. 2 dead, 4 wounded that I know of.

LikeLike

My Huey copilot was training with another unit and had a night alert. By radio misinterpretation, his helicopter flew over outgoing mortor fire and was hit. All 4 crew members died early March 1968.

LikeLiked by 1 person

As a Dustoff Pilot and Unit Commander, I am shocked by these statistics and horrified by the descriptions of these friendly fire incidents. My unit supported several of the victims of these terrible situations, but, we never knew of the circumstances. You asked, “Did you know that a soldier who is wounded or killed by friendly fire or other accidental means did not qualify for a Purple Heart?” In response I found this great website: Common Myths About the Purple Heart Medal http://www.americanwarlibrary.com/theheart.htm that reports a change of eligibility for the PH.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the feedback, sir. I’ll check it out and make the necessary changes. / John

On Tue, Apr 10, 2018 at 11:54 PM, Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLike

My first experience with friendly fire occurred sometime between October ‘68 and December ‘68. We were in a newly built fire support base outside of Tay Ninh. I was with the 4/23 mechanized infantry of the 25th Infantry Division. In the hours not long after dark mortar or artillery rounds started landing outside the perimeter of the fsb. No one was killed or wounded and it turned out that the rounds were fired by ARVN’s who we were told did not have us on their charts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

For pdoggbiker, or anyone else who can answer. I would like to know the following. I am sending thiss out a second time because apparently I answered in the wrong place.

1) When the coordinates for an enemy assault by air are made who sends out the coordinates? Does the radioman send out the coordinates or does the officer in charge of a platoon (a lieutenant, for example) send them out himself?

2) Are the coordinates which are sent out calculated by the officer in charge of, say, a platoon or by the radioman? Would an officer double-check all calculations done by a radioman if the radioman makes the calculations?

3) In other words, if an error in coordinates is sent out, who is responsible–the radioman or the officer in charge of a platoon?

4) Who actually reads out the coordinates on the radio–the radioman or the officer?

Thanks for any help you might offer. This is a very informative site.

Andrew

LikeLike

Andrew, this is a loaded question and I’ll try to answer it for you. During routine patrols, coordinates for night-time defensive perimeters are determined by the person in charge of the element. The grid coordinates are then given to the radio operator, who codes the numbers and forwards them to the firebase. Additionally, set targets around their night position are also identified, tagged as location A, B, C, etc., coded and forwarded. In the event of an attack on the perimeter, the person in charge might refer to one of his earlier plotted locations (A, B, C…) and just make adjustments from that point. This is primarily used for artillery support. During the attack and support, the team leader is in direct contact with the support unit.

When requesting air support, the person in charge of the element requesting the support will speak directly with the FAC pilot or other pilot to coordinate the attack. Normally, friendly lines will be identified by colored smoke and directions given from that location without using grid coordinates. Conversation will go something like this: grape smoke identified…concentrate on area north of smoke about 200 meters and make your run from east to west. This is an ongoing ballet until the battle ends or aircraft exhaust their ordinance. During the day, pilots might also see the battle on the ground and inform the team leader of enemy location and travel.

During company or larger sized operations, the battalion commander flies overhead and tries to coordinate the battle with the help of company commanders on the ground. Prior to any support, the unit commander on the ground may request a White Phosphorous round to explode in the air over a set location to help verify their location. However, when patrolling through 90 foot high jungles, it can be most difficult to locate reference points and accurately identify your coordinates. That spotter round may only help by sound to get you close.

I hope this helps!

On Tue, Jul 24, 2018 at 6:41 AM, CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

>

LikeLike

This is a great help, pdoggbiker. You covered almost all of the bases. I was thinking about smoke or White Phosphorous as a way to identify position, but forgot to mention it in my question. But your remark about thick jungle canopy answered that matter as an obstacle. Thanks much for your exhaustive answer. Andrew

LikeLiked by 1 person