Shell-shocked: Anthony Loyd goes in search of the Vietnam War veterans photographed by Don McCullin

The award-winning Times war correspondent has spent two years tracking down the traumatised young men whose images by McCullin defined the horror of the conflict. So what happened to those US Marines photographed 50 years ago this month at the battle of Hue?

This article originally appeared in The London Times on February 23, 2018. The direct link is included at the end of this piece.

The Marine was swallowed by the night. When he was found he was mute, though in his eyes lay a stare best unmet while dreaming: a gaze that was part trance, part fear, but mostly horror. The men who had located him recall that he neither blinked nor uttered a single word.

His true name is lost and his fate has become a mystery. But you may know his face already, for a photograph of him remains his only known legacy. Taken by Sir Don McCullin during the brutal battle for Hue in Vietnam 50 years ago this month, it is the portrait of the frozen man who became better known to the world by a clumsy caption: “Shell-shocked US Marine”.

Other than his photograph and those words, all that remains of the Marine at the centre of one of the most totemic war images of the 20th century are shards of memory, a half-century old, smoke-edged and bullet-griddled, from the few men who encountered him in the ruins of Hue and managed to survive.

It was to them I turned when I began to look for him. It took me nearly two years’ work to track them down.

It was monsoon season, February 1968, when the Marine went missing. The night air was cold and heavy with mist, which mingled with the smoke from burning buildings set ablaze by shellfire, reducing visibility to a few yards. To the US Marines crouched there, the city of Hue was reduced to snapshots of rubble and fog, which shrouded their memories of the fight there even before time eroded them further.

Long after the battle was over, the smell of smoke and fire and the bodies of the dead, the cold of the rain and the imprint of fear and grief came more readily to the minds of many of those left alive than any sense of orientation, time or visual depth.

Standing in the gloom of a ruined hooch, or shelter, on the front line in the southeast of the city, wearing a dead man’s shirt – his own had been ripped off by a North Vietnamese Army (NVA) rocket four days earlier – exhausted from lack of sleep and already twice wounded, Staff Sergeant Robert “Cajun Bob” Thoms waited for a pair of his Marines to report back.

He did not know their names. Thoms had been given command of a platoon from Delta Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, a few days earlier, and many of his new command had been killed or wounded after his unit reached Hue and became embroiled in the battle inside the city’s walled citadel. The turnover of casualties and replacements was so fast there was little time to get to know individuals.

That night, while consolidating a newly won block of houses near a street nicknamed “rocket alley” by the Marines, Thoms had sent the two men out into the darkened ruins to check a house to their rear was clear of NVA.

But only one Marine came back.

“Where’s the other guy?” Thoms asked. The Marine could not explain his absence.

“F***,” said Thoms. He collected a couple more men to search for the missing man, suspecting he had somehow been overpowered and killed by the NVA.

Minutes later, as Thoms and these Marines moved though the darkness of the house in which the man had disappeared, the sergeant saw something white in the corner of a room.

It was a face,” Thoms tells me. “I went over and this was the Marine. Just kinda sitting against the wall with his eyes open.”

The missing Marine – described as a tall, well built, good-looking man – was so still that at first Thoms assumed he was injured, and checked him for wounds.

“I thought someone had cut his throat, the way he looked,” Thoms recalls. “Because I’ve seen people with their throats cut and their eyes just wide open.”

But there was not a mark on the man, who neither moved nor spoke. Unnerved by this petrified figure, as the other Marines consolidated their positions around the house Thoms laid him down on the floor. At dawn he had his men fetch a young navy corpsman, a medic, to examine him. The corpsman duly checked out the frozen figure, then turned to Sergeant Thoms.

“Sarge,” he murmured, “his mind is not there. We need to get him out of here.”

———-

I started the search for the Marines in McCullin’s photographs in 2016, with just one name that the photographer recalled: Captain Myron Harrington.

The young Marine officer, in February 1968 a company commander aged 29, had already lost more than half of the 120 men under his command in the battle for Hue when he was told that one of his Marines was “not willing to participate in the action”.

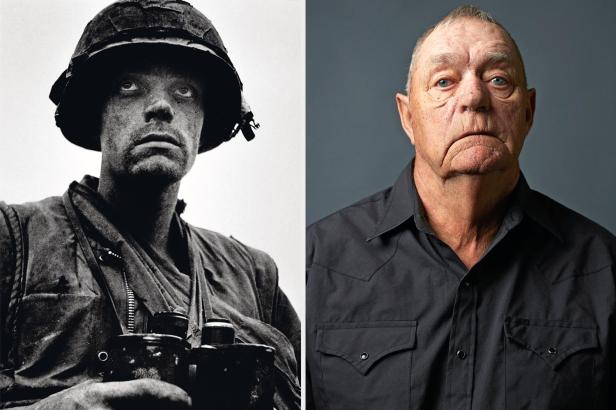

1968: Myron Harrington, Delta Company commander, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, shown sitting behind Don McCullin

Though he had been in Vietnam for six months and was an experienced career officer who eventually retired as a colonel, Captain Harrington had only been given command of Delta Company five days before the North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong launched the Tet offensive on the night of January 30, 1968. Within 24 hours, 80,000 communist NVA troops and VC guerrillas were attacking more than 100 different towns and cities across South Vietnam.

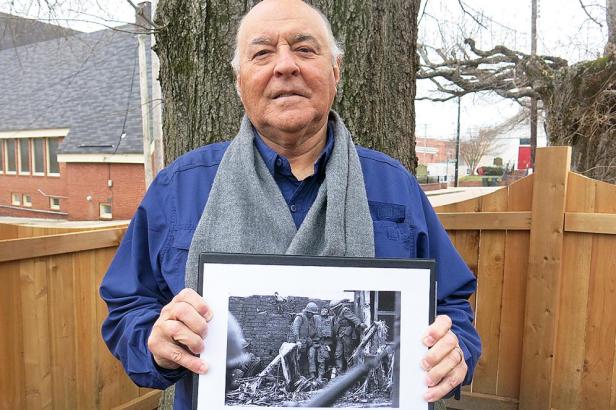

2018: Myron Harrington today Anthony Loyd

The communists’ plan was ambitious, and hoped to ignite an uprising against the South Vietnamese government and its US allies. That uprising never materialised, and in most areas the communist forces were quickly defeated.

But in Hue the story was different. The city, a former capital of Vietnam during the Nguyen dynasty sited on the Perfume River 430 miles south of Hanoi, was captured almost in its entirety by thousands of regular NVA troops within hours of the start of the Tet offensive.

On the north bank of the river, Hue’s ancient citadel provided an ideal defensive location for these fighters, protected by a stone wall that was in places more than 20ft high and 30ft wide. Access was only possible by a number of arched gateways, overlooked by towers that gave the defenders a commanding view of any attacking force. And inside the citadel, a network of smaller walls, alleys and canals further complicated the plans of the US Marines tasked to recapture Hue.

US commanders underestimated the forces they were up against in Hue, and it took 4 weeks and 1,800 US casualties before the city was finally recaptured. The battle proved to be the turning point of the war in Vietnam: the intense urban fighting and scale of casualties shocking the US public so that never again would they believe the official narrative of the war suggesting that the communists were nearing defeat.

Delta Company was committed to the struggle on February 15, after entering the citadel through its northeastern gate. The ensuing ten days saw the heaviest fighting of the battle. Overall, the week of February 11-17, 1968, was the worst for the Americans in the entire Vietnam War, with 543 US troops killed and 2,547 wounded. Overall, 16,592 Americans died in Vietnam that year.

“I went into Hue with approximately 120 Marines in Delta Company,” Harrington tells me when we meet. “By the time the battle was over at the end of February, I had 39 still standing.”

Fifty years after the battle, Harrington still appears deeply bonded to the Marines he commanded there, although he had entered the city to fight a lonely figure, knowing few men in the company he had so recently been given to command.

“When you share the battlefield and the communion of blood and guts that occurs there, every emotion an individual has is forthcoming,” he says. “We all feel fear; we all feel apprehension. You are watching each other, in some cases, die. The attachment you have for those people stays with you for ever.”

Plunging from the forging fire of this sacrament fell the shell-shocked Marine. It was early in the morning of February 21 when Captain Harrington was called to see the traumatised man, who was being escorted away from the front towards Delta Company headquarters by two of Sergeant Thoms’s men.

“He was in a state of shock,” Harrington recalls. “He had the classic thousand-yard stare, and was kind of frozen. I ordered that he be evacuated. That’s my last sighting of him.”

I hand him McCullin’s picture to double-check we are talking about the same man. We are. Harrington stares at the details I am so familiar with: the filthy flak vest and combat jacket; the stubble; the bitten fingernails; the pen in the top left breast pocket; the suggestion of tattoos on the man’s left knuckles.

This was no newly arrived grunt; no “FNG” – “f***ing new guy”. This was a seasoned veteran, broken by a moment of war we could only guess at.

“The human mind can only take so much,” concludes Harrington. “If we had taken him behind a building and slapped him around a little bit, would he have come out of it? I don’t know. But it was imperative to get him out of the battle area as quickly as possible.”

Minutes later, the shell-shocked Marine was escorted to the Delta Company command post, situated in a small yard beneath the citadel’s eastern wall. He was left there awaiting evacuation, as Delta’s most senior NCO, Gunnery Sergeant Odell Stobaugh, tried and failed to communicate with the staring man.

McCullin appeared. The photographer, then 32 years old, had arrived in Hue a week earlier on assignment for The Sunday Times. There was no formal “embed process”. He had crossed the Perfume River on a barge filled with reinforcements and assimilated himself with Delta Company inside the citadel.

Now, on seeing the frozen Marine, he dropped to one knee to photograph the traumatised man.

Eric Henshall, a 24-year-old Marine sniper attached to Delta Company in Hue, 1968, and pictured at home in Arizona this month DON MCCULLIN/PATRICK FRASER

“I noticed he was moving not one iota. Not one eyelash was moving,” McCullin says. “He looked as though he had been carved out of bronze. I took five frames and I defy you to find any change or movement in those frames.”

Then the photographer left the yard. Minutes later, at 7.45am, an NVA rocket hit the edge of the wall above the command post, air-bursting shrapnel onto the Marines below. Seven were wounded, including Stobaugh.

Private First Class (PFC) Eric Henshall, a Marine sniper attached to Delta Company, was there when it happened, and the explosion threw a lump of debris right between his eyes, which hurled him to the ground, semi-conscious. For Henshall, it was the end of what had already been an eventful battle.

“Hue was flattened,” he tells me. “The wall was in pieces. You saw bodies everywhere. The USS New Jersey was firing over our heads at one point from about 25 miles out. It was like a freight train coming over your head. Hue was just a mess.”

One week earlier Henshall had won the Bronze Star after sniping the NVA crew of a 126mm rocket launcher, before calling in tank fire that had wiped out the survivors. As part of a two-man sniper team he had crawled as close to the enemy position as he could, and spotted through his binoculars as his sniper partner shot one man before Henshall grabbed the Remington 700 rifle for himself.

“I got seven of them.”

Twenty-four hours later he was wounded in the legs, but returned to combat after two days, when McCullin took his image in one of the most haunting portraits of the battle: “The Sniper”. Twenty-four years old at the time, Henshall was born in Glasgow. His father was a soldier killed in 1943 in North Africa, and his mother emigrated to the US six years later. The Glasgow boy entered the fight in Hue with gusto.

Not one veteran I met could talk me through their Hue experience as a contiguous story. Instead, their recall consisted of memory slices, which often included searing detail and black holes. Though McCullin recalls speaking to Eric Henshall for some time during the battle while taking his photograph, Henshall remembers nothing of the photographer nor the moment his picture was taken.

His memory of the rocket strike at the command post was also hazy and he could not recall the shell-shocked Marine. However, this highly decorated career Marine whose own courage was so publicly acknowledged drew no distinction between his own fixed stare in McCullin’s photograph, and that of the Marine.

“I look like that,” he adds, staring at the picture of the frozen man when we meet at his home in Arizona. “Something had to have happened to have me looking this way,” he murmurs. “I don’t know what it was, but it wasn’t good.”

———-

Although I always tried to focus my questioning on what each Marine recalled of the moment McCullin took their picture, if they remembered the incident at all then their answers always took me elsewhere.

Like Henshall, PFC Selwyn “S-Man” Taitt had no recall either of Don McCullin or the precise moment of battle in which he was photographed.

The young black Marine from the Bronx had joined the Corps as an alternative to a custodial sentence in 1966, signed into military service by his mother when he was just 16. He was one of a small group of Marines led by Sergeant Thoms who on February 16 had crawled up the rubble to capture the Dong Ba Tower, a strategic gateway overlooking the citadel that was the scene of some of the worst fighting of the battle.

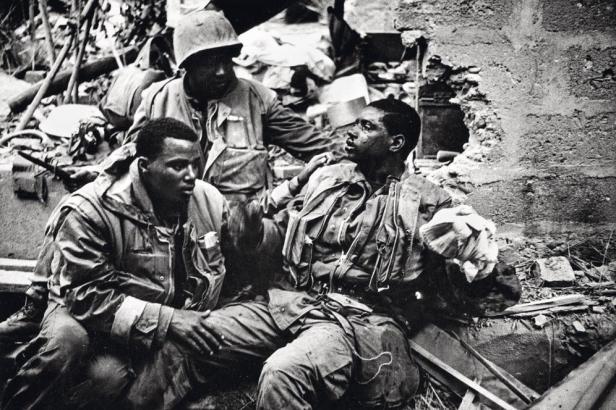

1968: Selwyn ‘S-Man’ Taitt (bottom left), the youngest Marine in Delta Company at 17 Don McCullin

“I can’t remember anything after Dong Ba,” he tells me as I sit with him and two of his sons, 45-year-old Skeet and Sean, 31, when we meet in Washington DC. “I blocked a lot out because I had to. I lost too many people there and the memories are too painful.”

In one of McCullin’s photographs from Hue, S-Man appears on the bottom left of a trio of black Marines, his hand on the knee of a wounded comrade. I noticed McCullin’s work in Hue swung between capturing the essential loneliness of individual Marines’ combat and moments of searing tenderness as Marines struggled to comfort their wounded or to save each other’s lives.

1968: Taitt may also be the subject of this McCullin image, captioned ‘US Marine throwing hand grenade’Don McCullin

S-Man may also be the subject in McCullin’s famous “athlete” throwing a grenade in Hue, an image that conjures up an Olympian moment as a black Marine hurls a hand grenade skyward over a vista of ruin.

“What the hell was I doing?” he muses, holding the photograph. “And what the hell was Don doing, too? We were both sniper’s bait.”

2018: Taitt today ANTHONY LOYD

It is an impossible photograph to verify, because the Marine’s face is hidden. Other Marines I met testified that S-Man had certainly hurled a lot of grenades during the action, but doubted he was the Olympian because his build was slighter. McCullin, an excellent witness, recalls the athlete as having been a big man, who was shot in the hand minutes later. Either way, other Marines confirm S-Man’s position in the trio picture.

Seriously wounded on two occasions in Vietnam, S-Man’s “back in the world” experience – the phrase Vietnam veterans used to describe returning home – had an inauspicious start. Within hours of landing in California he punched an anti-war protester who had spat on him in Los Angeles.

“The cops were called and I told them I had just got back in the world,” S-Man recalls. “I showed them my papers and they let me go.”

America was a turgid and divided nation in 1968, and whatever emotions a returning Vietnam veteran came home with were likely to be sealed inside their hearts – sometimes for ever – by the rabid anti-war sentiment they encountered the moment they landed back on home soil. Sniper Eric Henshall tells me one of his half-brothers had spat on him and called him a “baby killer” when he returned, adding that divisions in his own family over the war remain unresolved even today.

This combination of circumstances at home – solitude, hostility, uncertainty – provided fertile ground for veterans’ traumas to curdle into something much worse. And it was in this environment, with chronic PTSD, that S-Man sank into a mire of alcohol abuse and domestic violence, which kept aftershocks of the battle of Hue rolling out not just into the lives of his four marriages, but also into the upbringing of his eight children.

“It is another story that the Vietnam War gets to tell – the effects on the kids of veterans,” says S-Man’s son Sean, a social worker at the University of Southern California. “I felt the effects of his PTSD as a child, five or six years old. Pretty much my young adulthood and childhood was Dad’s PTSD attacks.”

During every interview with each Marine – usually at a point towards the end – came a moment of acute emotional resonance. Most often it involved grief. Twice I had turned off the recorder to allow a weeping man the time to compose in private. On another occasion it involved the intimate details of the killing of an NVA soldier in desperate hand-to-hand combat at night, with a knife, on a bed of rubble in total darkness.

This was such a moment, but the intimacy was not of killing, but of a family endeavouring to make its peace with the battle of Hue that still played out among them, and had resulted in years of domestic violence at home.

“I was abusive to his mum. I was abusive to all my wives,” admits S-Man. “I was out of my f***ing mind back then.”

He managed to hold down a job for 14 years as a paramedic after leaving the Marine Corps before burning out, and kicked drinking more than 40 years ago, but he still attends regular veterans’ group meetings to help deal with his PTSD and “the demons” the war yet unleashes.

“I was an asshole,” he tells me. “Their mums did not deserve what I gave them. The abuse. They were damned good women. I had the chance to go back and apologise to them. That much I did.”

———-

Today, thanks to the internet, it would be relatively easy to search for the identity of a contemporary US Marine in a photograph from, say, Iraq or Afghanistan. Yet no internet existed for returning Vietnam veterans. Moreover, they completed their tours as individuals and returned home alone rather than as a unit.

None of the Marines I found from either Delta or Charlie Company had maintained contact with one another after returning home. It was only the advent of mainstream internet use, and with it veterans’ sites and Facebook pages, that allowed some of them to reconnect 30 years after they fought in Hue.

Having first contacted Captain Harrington, within a few months I had managed to trace three other Marines from Delta. These in turn introduced me to other men among the network of surviving Hue veterans.

In tandem with this research, I secured a copy of the microfilm archives of Delta and Charlie companies’ unit diaries for the year 1968, as well as the 1st Battalion’s after-action report. The unit diary was essential, because it contained the daily details of casualty reports, and night after night, month after month, I pored through thousands of documents for February 1968, hoping to narrow down the identities of the shell-shocked Marine and the other men photographed by McCullin.

A major breakthrough occurred last summer, when McCullin mentioned that he had left the Marine in the company of Delta’s gunnery sergeant, and recalled that the gunny had been wounded minutes later by a rocket attack on the command post.

Knowing each Marine company only had one gunnery sergeant, I called Harrington, confirmed that his gunny was Odell Stobaugh, then cross-referenced that name with the microfilm entries to see which date he was wounded, thereby confirming the date and time McCullin had taken the photograph.

I was convinced that this was the eureka moment, and that by tracking down each man evacuated that morning I would identify the shell-shocked Marine. Yet I ran immediately into two problems. First, Odell Stobaugh, who would probably have remembered the name of the Marine, had died in 1999. Second, my faith in documentation as a primary verification method was misplaced. No record of a non-injury evacuation existed during the key week. Although I managed to track down the Delta Company clerk in California, he pointed out that in the bureaucratic bedlam surrounding the battle, the details of a non-physical injury may never have been recorded.

Other serials in the unit diary I found misdated, sometimes by weeks. Names appeared spelt in three different ways, accounting for wounds to different individuals when there was only one involved. One Marine was recorded AWOL when in fact he was in hospital wounded in action.

I hunted the shell-shocked Marine from the strangest places. During the nine-month battle for Mosul in Iraq, I sometimes returned from the front to scour microfilm details from Hue in my hotel at night, hoping that the weird link-up between the ruin of two cities would afford karmic aid. It didn’t.

Then at one point last year, staying in a dirty guesthouse on the Iraqi side of the Syrian border, waiting to cross over, I spoke with a go-between in the US who twice weekly met a severely traumatised Delta Company veteran in a café. A fragmented entry of a document suggested this might be the man I was after. The go-between duly handed this veteran a carefully worded and extremely gentle letter I had written asking for his help in identifying Marines in photographs from Hue. The picture of the shell-shocked Marine was attached. Yet the moment the man saw the photograph, the effect was terrible. He became distraught and walked out of the café. The go-between told me the attempt could never be repeated.

Yet I searched on, aware as I did so that with each voice of another veteran I encountered, so the ghostly, shell-shocked Marine became more a guide than a quarry. He had begun in my mind as the distillation of every man’s worst fear – frozen and reduced. Yet he changed. In his footsteps I met others, and learnt of time and war and grief and brotherhood, and how Marines grow old, but trauma never fades away.

———-

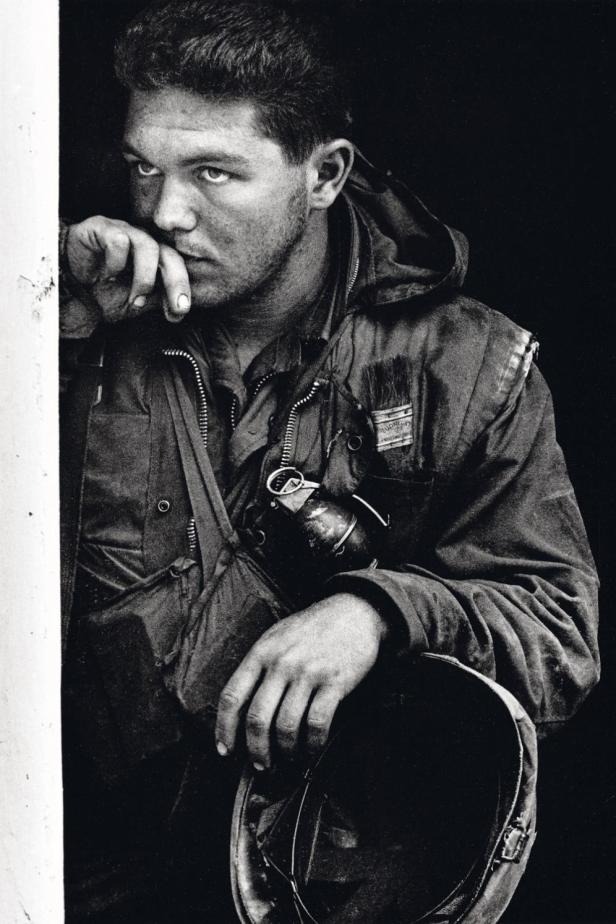

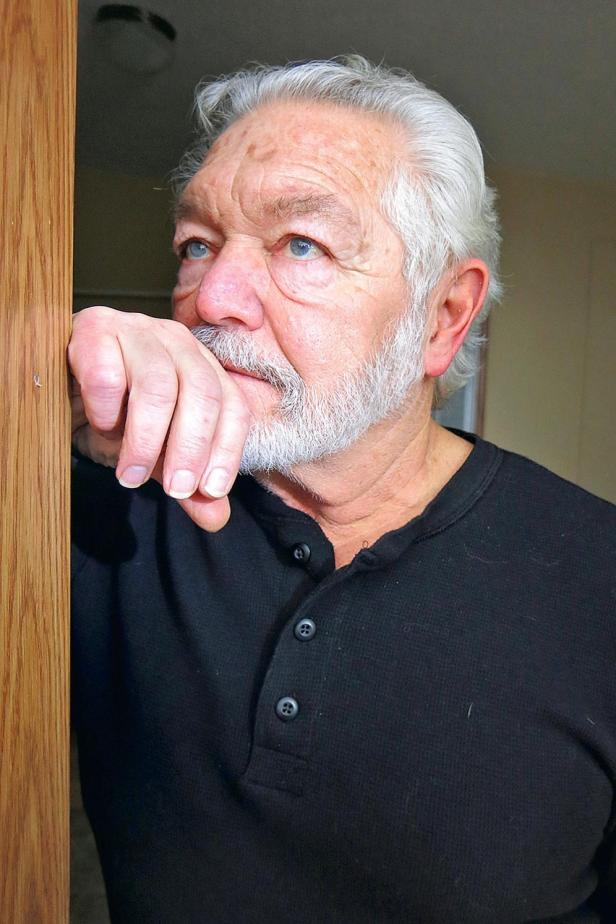

Not every Marine I met felt defined by the battle of Hue. In north Michigan, in the snow and cold, I meet Joel Adkins, known to McCullin as “the thoughtful Marine” after the photographer took his portrait leaning against a door jamb, helmet removed, in a moment of deep contemplation.

1968: Joel Adkins, H&S Company, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, pictured in Hue aged 20 Don McCullin

2018: Adkins in Michigan this month Anthony Loyd

Adkins was 20 years old and fought in Hue as one of the four-man crew of a 106mm recoilless rifle. His gentle voice combines with the softened sounds of the Michigan snowscape in a way that makes half a century feel what it is, and the war old and long gone.

Yet he has a clear recollection of the moment McCullin took his photograph.

“I was standing in a porch and Don come up and asked if he could take my picture,” he smiles. “And I thought, ‘Why is this guy running around without no weapons? This is another person we’ll have to take care of.’ ”

I ask Adkins if he knew what he had been thinking about at the time. Adkins mentions concluding “what a lousy war it was”.

It was not until 1996 that Adkins saw his portrait. Even then, it was an oil painting that his father had done of McCullin’s original that the Marine was shown, rather than the photograph itself. A family friend had seen the photograph in a magazine, and duly sent it to Adkins’ father, who painted it.

“It was not until 2014 that I saw the real photograph while I was looking online at some stuff about Hue,” Adkins laughs, as we sit in his dining room beneath his father’s oil version.

Towards the end of our second day together in Michigan, relaxed and easy in each other’s company, I connect a couple of casual remarks Adkins has made and ask what happened to the rest of his recoilless rifle crew. It transpires that they had been killed or maimed at the start of the battle when Adkins’ team was caught in an ambush near a canal. One man lost both arms in a rocket blast. After that Adkins had gone through the entire battle alone as the only crew member left, driving the weapon around on a four-wheel buggy, loading and firing it; performing the role of each of his fallen crew. “What a lousy war it was” was no brush-off line.

———-

There was never a pretender or claimant to be the shell-shocked Marine. No one was out there who years later said, “That’s me.” But many people wanted to be Richard Schlagel, the Marine with the octopus tucked into the band around his helmet, or thought that they might be the bandaged Marine he cradled in his arms aboard a tank.

I remember first noticing McCullin’s photograph of these two Marines when I was a teenager. Vietnam had always fascinated me and I had read the war’s essential bibles – Michael Herr’s Dispatches, Mark Baker’s Nam and Robert Mason’s Chickenhawk – with avid interest. The work of the war’s great photographers – Larry Burrows, Philip Jones Griffiths and Kyoichi Sawada among them – had enthralled me even more. It was the combined effect of these men that persuaded me later to become a war correspondent.

1968: Richard Schlagel, with the octopus in his helmet, tends to James Blaine, who died aged 18 Don McCullin

2018: Richard Schlagel earlier this month Anthony Loyd

The rubber octopus on Schlagel’s helmet, irreverent and cartoon-like, had always stuck in my mind, riffing off the desperation of the moment. What had become of him and the Marine he held? Now he sits before me and I am about to find out.

As so often, the conversation around the photograph begins much earlier, this time on Hill 110 in the Que Son Valley of South Vietnam in spring 1967. Many of the Marines I met spoke in similar sequence, starting the conversation months ahead of Hue, as if to lay the foundations for what had shaped them long before McCullin took his pictures.

“Hue was bad,” they seemed to be telling me. “But you wouldn’t believe the shit that happened before and after.”

On Hill 110, PFC Richard Schlagel, newly arrived in Vietnam, went on his first operation. It was a bloodbath. His unit, Charlie Company 1/5, ran into a larger force of NVA regulars. One by one, the Americans’ newly issued M-16 rifles began to jam as they advanced uphill under heavy fire. A mortar round landed in front of Schlagel. It threw a gunnery sergeant up into the air, killing him instantly.

“His body was smoking from the hot metal, and shaving foam squeezed out of his torn pack,” recalls Schlagel, who lay on his belly 15 yards below the body of the gunny. The same round critically injured a radio operator named Fred Tate, and Schlagel crawled over to him, giving him mouth-to-mouth to try to keep him alive. Next, responding to cries for water, Schlagel edged over to a nearby black Marine named Washington, who was sitting upright on the ground, and asked for his canteen. There was no response. He shook the sitting man. Washington was dead. When the fight ended Schlagel was shaking so much he couldn’t light a cigarette.

By the time the battle of Hue started ten months later, he was a veteran with only a little time left in-country, but the echoes of Hill 110 had stayed with him.

He remembers every moment aboard the tank in Hue, though nothing of the minutes before. But as he held the dying, bare-chested Marine in the foreground of McCullin’s image, memories of Fred Tate on Hill 110 came back.

“There were no signs of life,” he says of the wounded Marine on the tank. “I didn’t see any breathing or movement or anything. It was like I felt guilty because I lost Tate on Hill 110, and I really didn’t want to lose someone else that I was trying to help.”

The photograph became one of the best known among McCullin’s Hue pictures, and the figures aboard the tank received a double exposure of fame because the same vehicle was photographed minutes later, by which time more wounded had been loaded aboard, by photographer John Olson. McCullin concedes that Olson’s image, laden with desperate men in a way reminiscent of Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa, is the stronger picture.

What is extraordinary about both pictures is the number of men claiming the identities of those aboard the tank. These claimants include Marines who were wounded at other locations on different days in Hue mistakenly believing they are in the photographs, and outright frauds who never served in Vietnam at all but are part of the “stolen valour” phenomenon, whereby men claim the war experience of servicemen as their own.

“I have had dozens of people over the years claiming to be the Marine in my arms,” Schlagel tells me. “I just say, whenever they contact me, ‘Great. I’m pleased you made it.’ ”

There is no doubting Schlagel’s identity. (He still has at home the octopus that appears in the photo, minus a couple of legs lost in the jungle, which was given to him by his brother in a Christmas package in December 1967.) But the main point of contention, exemplifying both the fog of war and the passage of time, concerns the dying young man in Schlagel’s arms.

The dispute over this man’s identity most recently resurrected last year on the publication of Mark Bowden’s outstanding study of the battle, Hue 1968, in which the author and John Olson both identified the casualty as a man named Alvin Grantham, who survived his wounds and lives today. Grantham is a respected Marine veteran who was indeed shot through the chest – the wound exiting out of his shoulder blade.

Yet the testimony of the Marines present on the scene that day with whom I speak, combined with unique access to McCullin’s contact sheet of his images taken from the scene in the minutes before his famous tank photograph, suggest beyond any reasonable doubt that there was no happy ending for the Marine cradled in Schlagel’s arms. His name was James Blaine, and he had received a terrible gunshot wound that entered his right upper torso, breaking his spine, before exiting his lower left back just below the belt line.

The documentation around the event was – once again – inconsistent and contradictory, affording no more focus than a probable 48-hour time bracket in which the photograph had been taken. Yet the overwhelming body of witness evidence determines it to be James Blaine. I speak with Blaine’s platoon sergeant, John Erskine; correspond with his squad leader, Walt Markowski; talk to wounded Marines Leon Dyes and Jim Rice, who were both put aboard the same tank as Schlagel.

Next, I manage to contact Naval Corpsman Octavie Glass, who saw James Blaine shot and bandaged his wounds. The two men knew each other because Glass had been attached to Blaine’s unit, Charlie Company, since the previous autumn. Glass talks me through the scene – without himself having been given access to McCullin’s contact sheet of photos, which I follow with my finger as he speaks. Glass describes, unprompted, the schoolhouse where the sniper shot Blaine, the desperate scramble to bandage his wounds, and confirms McCullin’s presence with Charlie Company that day (“He gave us some orange sweets and told us how American soldiers gave him chocolate in London during the Second World War”).

“I saw James buckle and go down,” Glass adds, as I stare at McCullin’s images of the scene he describes with such chilling precision. “The entry wound was in his chest; the exit was his lower back near the spine. For a while he could speak and said he was burning in his stomach. He couldn’t feel anything in his legs. By the time we got him on the tank he was in shock and did not speak again.”

Blaine died the same day. It was February 15, 1968. The shell-shocked Marine may have always been one step ahead of me. But in his footsteps other mysteries ended.

———-

Myron Harrington says the shell-shocked Marine never came back to Delta. Thoms tells me that he later heard the Marine had been sent to a psychiatric ward in a catatonic state. The personal medical records are not accessible. The trail went cold. I had walked through the valley of the shadow of Marines’ memories in search of him all the way from DC to Tennessee, from the Arizona sun and into the snows of Michigan – and I lost him.

Yet there was one more Marine that I found while looking for the frozen man, and I will leave you with his account, for every detail of this man’s story glowed with the wealth of a hard-fought internal peace. He was not alone in that. I found Marines who had made their own peace with Vietnam. But “Frenchie’s” words held particular resonance, and if I wished an epitaph for the shell-shocked Marine, it would be written in Frenchie’s final words to me.

His full name is Melvin “Frenchie” Bourgeois. He is from south Louisiana, and is the Marine in the centre of McCullin’s own favoured photograph from Hue.

I have not shed the memories. But I have shed some of the burden

Every story here involved pain, and Frenchie’s was no different. He was the Marine in the photo captioned “Crucifixion”, in which he is held, his arms over the shoulders of two comrades, his head leaning back in pain, an NVA bullet wound to his left hip.

(In the telling, as with every Marine, the greatest pain is grief, and Frenchie’s mellifluous southern drawl is at one moment rendered by a sob when he recalls the death of his platoon commander in Vietnam, a hugely respected officer named Lieutenant Jack Imlah.)

McCullin photographed Frenchie on February 17. They had met as Delta Company Marines edged further along the southern wall, clearing NVA spider holes as they did so. The wall here was about 30ft wide and the spider holes were essentially tiny bunkers dug into the top of it, often concealed and wide enough for just one or two North Vietnamese troops, who would engage the Americans as they moved along the wall.

Frenchie, 18 years old at the time, had already met McCullin and told him to stay close to the wall as his platoon advanced.

“I remember telling him, there’s a lot of action going on,” Frenchie says. “There’s a lot of shooting and it’s quite dangerous. I don’t know how many Marines we’d had wounded or killed by that time. I encouraged him to stay close to the wall. We weren’t focusing on him. We had a fight going on.”

2018: Melvin ‘Frenchie’ Bourgeois today Anthony Loyd

Knowing an NVA fighter was hidden in a hole before them, Frenchie told his squad to lay down covering fire as he crawled up towards the spider hole with a hand grenade. At the final moment he lifted himself to a squat to hurl the grenade, which missed its target. Instead, the NVA soldier shot Frenchie in the groin. The bullet went into his left upper thigh and exited from his buttock. The Marine fell to the ground, certain that his own men had accidentally shot him in the arse, because the exit was where it hurt most.

“I told you not to f***ing shoot me,” he yelled at them.

Dragged to the cover of a wall, he was treated by two Marines and a medic. As they lifted Frenchie up, McCullin took his photo. But the connection did not end there.

Every Marine was needed for the fight, so McCullin offered to carry Frenchie down from the wall. Amid the crackle of gunfire he held the Marine over his back so that Frenchie’s arms were over his shoulders, his body and legs draped down.

At some point he stumbled and fell, a moment each recalls, as they negotiated the steps down from the wall to a “mule”, one of the low four-wheel utility buggies the Marines used to carry wounded and ammunition. It was the last time he ever saw McCullin. But just a week later, in a US naval hospital, writing to his mother and sister a letter to allay their fears, Frenchie described the incident.

“Hi Mom and Sis,” the letter begins as he reads it to me in Tennessee at the home of the lady who had introduced us. “We had been in the city about five days when I got hit. Our company had a photographer. He was the one who carried me back to the rear where it was safe when I was hit. To me, he was a very brave guy. Before I was shot he was taking pictures of me because I was trying to get one of those NVA out of a hole.”

Frenchie recovered and later returned to duty in Vietnam with Delta Company. A few months later, the man in front of him triggered a booby trap. Frenchie received a sucking chest wound.

“Well, if Don called me the subject of a crucifixion in that first photograph,” he tells me, laughing, “he should have seen me the second time I was hit: I looked like Christ being stabbed with a spear – I had blood and water spurting out of my chest.”

He recovered, and continued to serve in the Marine Corps until 1972. It was not until 2016 that he saw McCullin’s photograph.

“I have not shed the memories,” he says as we sit discussing the war together and day begins its fade. “But I have shed some of the weight, the burden that you pick up in war. The losing of friends – I haven’t forgotten them. I’ve just put it in a place where I can manage that, and live peacefully. I can still have those memories, but in such a way that I am at peace with that. I am OK with my past.”

I was unable to copy/paste the author’s 6.5 minute video with actual footage while the above TET photos were taken. I urge you to visit the article at watch it… https://www.thetimes.co.uk/past-six-days/2018-02-24/the-times-magazine/shell-shocked-anthony-loyd-goes-in-search-of-the-vietnam-war-veterans-photographed-by-don-mccullin-cz3dmmnng

***Mr. Hugh B. Scott provided the following additional Information about the photosPublished By MICHAEL SHAW on FEB. 19, 2019 in the New York Times Magazine…

https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/02/19/magazine/vietnam-war-photo-wounded-marine.html

****A new article provided by Rob Blaine (brother of James Blaine) which further discusses the debate regarding the true identity of the Marine on the tank. Hands down, it points to James Blaine. Check this out: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/02/19/magazine/vietnam-war-photo-wounded-marine.html

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

Thank-you for your honest, riveting, and gut wrenching article. And thank-you for pointing to the truth in regards to identifying Mr. James Blaine as the tragic figure on the tank. I certainly believe the account of the man who is holding him in the picture over the accounts of others who might be trying to push a “feel good” narrative of the brave Marine who survived his catastrophic injury.

And, I’m sorry, but Mr. Blaine had movie star good looks. Mr. Grantham was a pretty ordinary looking guy. It’s glaringly obvious, to me, that the man who’s lying on the tank is a handsome man. Mr. Grantham did not have such broad shoulders either….

I have no doubt that Mr. Grantham suffered a similar injury and was transported under similar circumstances at a similar time, but I’m sure he was one of many, as was Mr. Blaine.

I’m so sorry to the family for the senseless loss of such a beautiful young man. And so sorry for all of his mates who either died or were traumatized for life by what they went through.

But, above all, thank-you for being one of very few who are standing up to tell the true story rather than trying to bury it and stick to the accepted Grantham narrative that has been around for decades. It’s time to set it right.

LikeLike

Thank you!

LikeLike

John

Just discovered your web site. Thanks for spreading Anthony Loyd’s article on the shell shocked Marine and Michael Shaw’s article about the true identity of the Marine on the tank in Hue. I won’t lie, I have a vested interest, the Marine on the tank was my brother, Jimmy Blaine.

Chris Chivers, a Marine combat veteran and writer for the NY Times, weighed in on the topic at the address below. He and other Marine combat vets write for a NYT on-line magazine called “At War”. Thought you might be interested.

Keep up the good work. I look forward to following your site.

Thanks

Rob Blaine, Boise ID

PS An Army digital historian named Erik Villard saw the story and did some research. He noticed that the tank in Sir Don McCullin’s pictures had ID number A52. He looked up the records for that tank – it was damaged and en route out of Hue for repair on Feb. 15. It wasn’t in Hue on the 17th. Additionally, his digital analysis of Jimmy’s and Grantham’s 1968 pictures in dress uniform indicate, according to him (remember what he does for a living) that it is James Blaine, not Grantham.

LikeLike

Rob, thank you for the commentary and link. I’m most appreciative and readers will now also have the opportunity to read about the facts regarding your brother’s death. Sorry for your loss. RIP James!

On Sun, Mar 24, 2019 at 1:27 AM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

>

LikeLike

Some Additional Information Published By MICHAEL SHAW on FEB. 19, 2019 in the New York Times Magazine…

LikeLike

Thanks Hugh! I will add your information to the end of the actual article. I’m very much appreciative of your submission. / John

On Wed, Feb 20, 2019 at 3:07 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

>

LikeLike

Howdy, I really enjoyed this article. It was so gripping and emotional just to read about Hue that I read it in parts. I confess mixed feelings re locating the shell-shocked soldier. Maybe being discovered would have some negative consequences for a man who might have found some peace in the interim? I suppose this sort of thing cuts to the heart of moral choices in journalism. Regardless, your article, Don’s photos, and the testimonies of Marines will be in my mind for a long time. Thank you all.

LikeLike

. I’m my name is Richard Schlagel I am the Marine holding the shirtless Marine. I only know one

Marine on that tank. That is James Blaine he member of my fire team he is holding the IV bottle. The Marine I’m holding was shot in the chest and it came out down by his belt line. At no time did this Marine move or take a breath or even show any signs of excruciatingly pain.

The three Marines behind me on the tank are Jim Rice, Dennis Ommert and the last Marine . On the tank is Clifford Dyes. They were W.I.A on Feb. 15 1968. People Weekly Magazine found the Marines that were on the tank and took their stores in (issue April 29, 1985 VOL.23 NO.17)

Than in People Weekly issue (June 3 1985 VOL.23 NO.22) in the MAIL section Doc Glass wrote.

As a Navy corpsman attached to the First Marine Division in Hue Vietnam. I bandaged the shirtless man lying on the tank picture in your April issue. His name was James Blaine. He was critically wounded.

AB Grantham claims to be the shirtless man on the tank he was shot through the chess and it came out his shoulder blade. He said I had two broken ribs of course. It was so painful, the ride. The ride was excruciatingly painful,

Richard Hill said he also on that tank and he the last Marine on the tank the one with the bleeding leg. If you look closely at Olson picture the Marine with the bleeding leg is resting his leg on the last man leg. You can see the last man unity trousers and the toe of his combat boot right behind the bleeding Marine foot. Hill claims to be the man with the bleeding leg. Hill also clams to be the last man on the tank. Can’t be both

They were both W.I.A. Hill on the 02/16/68 and Grantham on the 02/17/68

I guess they been telling people that them in the picture for years.

All I can add is I was their and I’m holding the lifeless Marine in

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the clarification, Doc!

On Sun, May 20, 2018 at 1:48 PM, Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLike

I was a grunt not a corpsman they were needed in the city.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sorry bro! I stand corrected. Semper Fi!

LikeLike

OK pdoggbiker,

How about using your influence to contact author MARK BOWDEN and let him know he got his HUE 1968 STORY WRONG, when he identifies the “shirtless Marine” as A. B. Grantham.

LikeLike

Are you James Blaine?

You are being asked to login because mattblaine13@gmail.com is used by an account you are not logged into now.

By logging in you’ll post the following comment to The search for a soldiers’ identity in 1968 TET photos:

Richard Schlagel, thank you for your words and recollections. I am Jimmy’s nephew. There are about 35 nieces and nephews Jimmy would never meet, but we all think about him all the time. I think most of us understand that everyone that went to Vietnam should be commended. This confusion over the exact identity of who was the “shirtless marine” on the tank perhaps goes to show us all just how important it is to GET IT RIGHT, the first time. I can’t imagine the sacrifices you all went through, and Hill and Grantham obviously sacrificed as well. Some of Jimmy’s brothers(my dad was 20 at the time) and sisters may not have wanted the exactness of a positive ID, however over time it does seem to help and heal knowing who it was and not questioning or wondering over and over. For what it’s worth, Jimmy’s nieces and nephews will Never Forget.

(Mr. Schlagel, if at all possible and if you’d be willing, I know a few of my family members would be interested in an email exchange or phone conversation with you. If that was something you’d be willing to do. If not, I respect your decision in the utmost way.)

James Matthew Blaine

mattblaine13@gmail.com

LikeLike

My thoughts are that you should do a “special blog post’ on getting history correct once and and for all regarding “THE SHIRTLESS MARINE IN JOHN OLSON’S’ ICONIC PHOTO” and Sir Don McCullin similar, but numerous photos of the same event. Author Mark Bowden has to make the correction of the identity of “the shirtless Marine” in his book “Hue 1968 as well as the identity at the exhibit in the Newseum in Washington D.C. about the 50 year anniversary of Tet. The facts as I understand them are: (1)

John Olson did not date his film rolls and assumes the picture he took was Feb. 17. when Alvin Grantham was wounded and placed on a door and then put on a tank. (2) The Olson photo was actually taken on Feb 15, 1968 the same day Sir Don McCullin took the similar picture. (he dates his film rolls). (3) Richard Schlagel, the Marine with the “squid” in his helmet band knows he was holding James Blaine on Feb. 15, 1968 and that James Blaine did not survive his wounds.

The Marines do not need another 70 years of misidentification of their hero’s and there identity like the FLAG RAISERS ON IWO JIMA in World War II.

LikeLike

I am friends with an ex Marine , Richard McGill, who fought at Hue during the Tet Offensive. He still fights the battle to this day. He was the gunner on a 106 MM Recoilless Rifle. He now lives outside Houston, Texas.

LikeLike

I was also 106’s attached to Delta 1/5! Who was McGill attached?

LikeLike

Not trying to be smart or rude but he is not an x marine he will always be a brother marine thank you for recognizing him

LikeLiked by 1 person

Sgt FK Abbott viet nam combat vet 1966-68

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is a very sobering article. A friend told me that reading it almost gave him PTSD. Only those of us who were there can fully appreciate the sacrifice.

John Podlaski, how do I communicate with you? I would like to submit an article for your consideration.

Respectfully,

Jim Van Straten

LikeLike

Send me an email: john.podlaski@gmail.com

On Tue, Mar 6, 2018 at 12:26 PM, Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel wrote:

>

LikeLike

This is one of the most touching and impressive articles I’ve read so far about ‘Nam. It send shrivers down my spine.

LikeLike

#1

paul (swirl) dickson

D Troop

3/5 Cav

’67-’68

nonattyspksprzn@gmail.com

One is angry number

To be twisted into believing

Then counted

And left behind

LikeLike

What an amazing heartfelt emotional story. In writing the song You Took My My Picture, the following verse relates to the article: “you took my picture in the battle of Hue, you took my picture I started to pray. I was a Marine in ‘68. I’m not coming home anymore.” Then we produced the music video and I think the Marine in the video is the Marine in this article. Let me know what u think. Writing the song and producing the music video was tear jerking emotional for me.

LikeLike

I was stationed at the Navy Photo Center at NAS Anacostia, which is now Joint Base Bolling-Anacostia when all of this was going on. It seems strange to look back at it now.

Very good article, John, and I’m glad you posted it. because I think keeping history as accurate as possible is important.

LikeLike

Great share, John!

Just want to point out that the caption of the wounded marine on the tank is incorrect (I know, it’s not yours, but The Times’).

Some more pics of that moment:

http://www.alphaonefive.com/identified-photos/ – still, that page mentions the wrong guy (who was killed 2 days before: http://www.honorstates.org/index.php?id=262551).

Last year I read this article – his name is Alvin Bert Grantham:

https://www.vanityfair.com/news/2017/05/the-true-story-of-the-marine-on-the-tank-vietnam-war.

And some ‘weird’ video:

So at least one TET-marine has been identified properly – and gladly he could share it with us.

LikeLike

This shirtless Marine is NOT ALVIN BERT GRANTHAM.

THIS MARINE IS JAMES BLAIN, KIA Feb.15,1968.

Will the podmastern please do a special article to properly correct the record

LikeLike

Update your info. What you’ve been reading is the guys protecting their image and monied empire. Anthony Loyd, along with Michael Shaw, have a tremendous amount of data pretty much confirming it’s Blaine.

If you’re not convinced, well…?

LikeLike

First of all: it’s not ‘my info’ – I linked to an article a year after it was published (it now is 2 years old, my post is more than a year old – the NYT-article is only a month old….).

Second: I trusted the article in a ‘reputed’ magazine – I assumed (!) they did their research. Apparently not. So, as your president says, ‘fake news’, the media can’t be trusted…

Third: “…guys protecting their image and monied empire” – please explain. Other than that, how am I supposed to know, reading an article in a ‘reputed’ magazine?

Apart from all of that: thanks for your other post(s) here. And sorry for the loss of your brother – I posthumously thank him for his service.

LikeLike

Done.

On Sun, Mar 24, 2019 at 11:04 PM CherriesWriter – Vietnam War website wrote:

>

LikeLike

It was a terrible war over there for all of us, we had no support from anyone except ourselves. We were young and bursting with patriotism anxious to explore this strange with no knowledge of the enemy, rifles that were undependable and very little equipment to fend off attacks. We were consistently outnumbered by our enemy plus out of date maps to guide us through the country, how I managed to stay alive still haunted me to this day. Outstanding article Sir!!! Once a Marine, always a Marine!!

LikeLike

Very moving article,nice to see these people getting recognition for what they did, Semper Fi

LikeLike

“The search for a soldiers’ identity…”

PLEASE. He’s not a soldier. He’s a Marine.

Semper fi, my brother.

LikeLike