A unique force of riverine vessels sought and successfully plugged the Viet Cong’s river supply routes by applying amphibious search and destroy tactics that hadn’t been used by the American military since the Civil War, a hundred years earlier.

The Mobile Riverine Force fought a war like no other in Vietnam. Most always wet, often feverish and forever scared, the youthful Army grunts of the 9th Infantry Division fought a type of warfare for which the Marines had been better trained, but wouldn’t take on. Theirs was the war of the treacherous mangrove swamps of jungle so thick you couldn’t see your buddy three feet in front of you. And when you saw someone you hoped it was friend, not foe. This was the war of the Mekong Delta, a sprawling inland waterway which the Riverine Force was charged to patrol and deny the use to the enemy.

An assault support patrol boat (ASPB) of Task Force 117 slowly moves up the outboard quarter of an armored troops carrier (ACT) as it sweeps for Viet Cong command detonated mines. Despite the determination of the enemy the ruggedly built vessels, mostly converted landing craft were tough to knock out and could take a lot of punishment.

As with most combat in Vietnam it was a relentless series of deadly firefights, swift and final and often inconclusive. The object was to interrupt the Viet Cong’s supply routes and the Riverine Force was so successful at it that by the late ‘sixties the enemy was forced to use inland supply routes rather than the more convenient and efficient waterways of the hot and humid Delta region.

For the most part the GIs of the Army’s 2nd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division and Allied units suffered more from the ravages of jungle rot, pestilence and fever than their counterparts fighting on the high ground. Rain in the Delta was incessant, humidity appallingly high and personal comfort all but nonexistent except when the troops returned to their air conditioned barrack ships after a search and destroy mission. But like their weapons toting brethren fanning across Vietnam’s troubled headlands, they fought and died and lived and laughed with typical American zeal and humor.

Army grunts of Company B 3/60th Battalion return to a River Assault Flotilla One armored troop carrier (ATC) following a search and destroy mission in the Rung Sat zone of the Mekong Delta in October, 1967. Note they keep their weapons dry as they wade through the waist deep much fatigued from fighting the heat, flies, jungle rot and the elusive enemy.

The Mobile Riverine Force (MRF), was a unique Army-Navy strike force in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. The first riverine warfare unit to be established by the United States since the Civil War, the MRF was a mobile assault force which conducted search and destroy operations on the intricate network of rivers and canals in the Mekong Delta. The fleet of Navy river boats provided close support and fire power while lifting and helping to maintain Army troops in a combat area for two to three day search and destroy missions.

Both the troops and the boat crews were based aboard shallow draft Navy support ships especially modified for operation in the Delta. The smaller river assault craft provided close fire support, block, and patrol of the waterways in the area immediately prior to the troop landing, during the assault, and throughout the search and destroy mission.

The ground assault unit of the Riverine Force was the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army’s 9th Infantry Division which was commanded by colonel Bert A. David, USA. Two battalions from this brigade teamed with the assault boats of the U.S. Navy’s Task Force 117 commanded by Captain Robert S. Salzer, USN. All search and destroy operations were determined, planned and executed through close coordination and cooperation between the Army and Navy commanders and their subordinates.

The first staff members of River Assault Flotilla One, the administrative title of Task Force 117, arrived in Vietnam in October, 1966. Three months later on January 28, 1967, the 2nd Brigade arrived in country at Vung Tau, a coastal seaport 35 miles southeast of Saigon.

The Navy’s first increment of the riverine assault boats were not due to arrive until March, but during the early days of February 1967, the Viet Cong increased the tempo of attacks on U.S. and Allied shipping in the Long Tau Channel, the main shipping route between Saigon and the South China Sea. On February 16, a decision was made to press the Mobile Riverine Force into immediate service, using borrowed boats and other equipment from the Vietnamese Navy to conduct search and destroy operations in the Rung Sat Special Zone to begin clearing approaches to and near the upper Long Tau Channel.

Initial operations proved highly successful. By early April the task had been completed in the Rung Sat area when it was decided to move the Mobile Riverine Force into other areas of the Delta. It first went to Dong Tam in Dinh Tuong Province. Later it moved to such places at Kien Hoa Province, Bien Hoa Province, Long An Province, and Co Cong Province.

By late May all five ships which formed the Mobile Riverine Base (MRB) had arrived in the Delta. These included two self-propelled barracks ships, the USS Benewah (APB-35) and USS Colleton (APB-36); a landing craft repair ship, US Askari (ARL-30); the barracks ship APL-26; and a logistics support LST assigned on a two-month rotational basis by the Commander, Seventh Fleet.

Navy PBR (Patrol Boat River) and crew on patrol in one of the narrow riverways

These five ships provided repair and logistics support, including messing, berthing and working spaces for the 1,900 embarked troops of the 2nd Brigade and the 1,600 Navy personnel assigned to Task Force 117. The Benewah also served as the Mobile Riverine Force flagship. By mid-June 68 riverboats had joined the force and others would be arriving every few days until the full complement of 100 river assault craft had been reach on February 23, 1968.

By June it was possible to conduct approximately six to either search and destroy missions per month, each lasting two or there days. On at least eight separate occasions during the year, more than 100 Viet Cong were killed on a search and destroy operation, some of which were conducted jointly with South Vietnamese military forces.

The battle of December 4-6, 1967, in western Dinh Tuong and eastern Kien Phong Provinces is regarded as the MRF’s biggest single engagement. In this battle, the combined forces of the MRF and the Fifth Battalion of the Vietnamese Marine Corps met and defeated elements of the Viet Cong 502 Local Force and 267 Battalions. Two hundred and sixty-six Viet Cong were left dead on the battlefield and 52 communist weapons, 182 grenades and 5,000 rounds of ammunitions were captured. In addition, 161 bunkers, 126 sampans, and eight command structures were destroyed. Allied losses were 52 killed in action of which 11 were Americans. MRF assault craft participating in the battle were hit by a day-long barrage of enemy gunfire and rocket fire without loss of a single boat.

Four basic types of assault boats had been designed for MRF operations, each commanded by a senior petty officer.

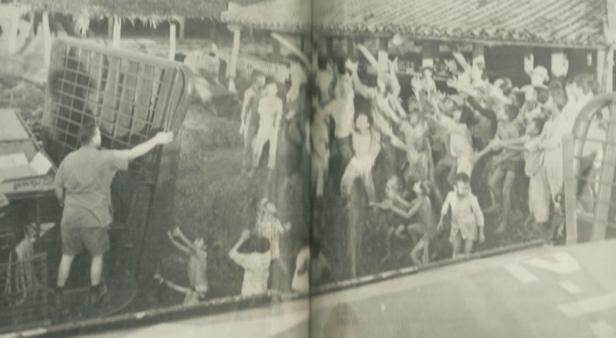

All was not deadly combat as this scene vividly portrays with crewmen of a beached Mobile Riverine Force ATC throwing cans of C-Rations to eager villagers who were safe from Viet Cong threat – for the moment anyway

The primary mission of the armored troop carrier (ATC) was to transport Army soldiers into combat areas. Each ATC was capable of carrying a platoon of 40 fully-equipped infantrymen into virtually any canal, river, or stream in the Delta. Bar-trigger shield and a special hard grade of steel plate protected the ATCs against enemy recoilless rifle and small arms fire. Many of the ATC’s were reconfigured with a helicopter deck to accommodate flight operations for medical evacuation, resupply and personnel transfers.

Protecting the troop-laden ATCs were the ironclad monitors, the battleships of the river fleet. The monitors have more firepower than any other boat in the flotilla and were designed to stay on the scene and battle it out with the enemy once contact occurred.

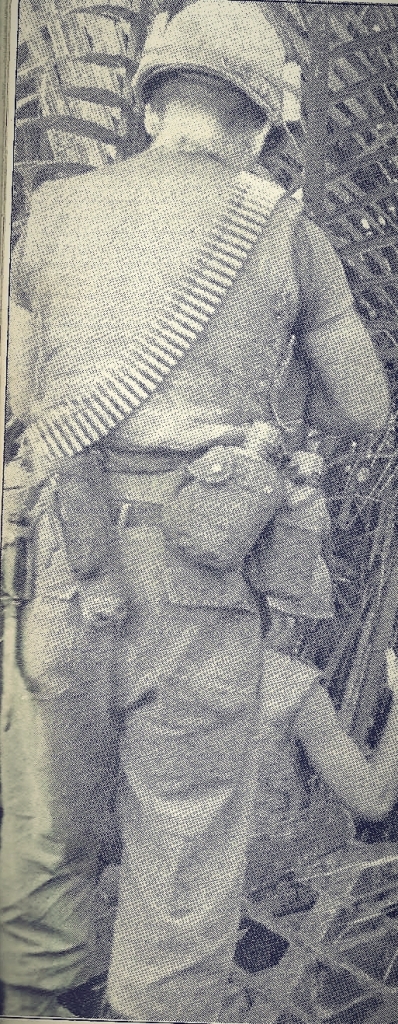

A rotten stinking vocation by any standard, the grunts of the 9th U.S, Army Division were usually soaked from the rigors of their amphibious missions. Jungle rot and fever took a high toll despite the efforts of medics who couldn’t combat the everlasting pestilence of flies, lice leeches and poisonous water snakes.

Serving as the destroyer / minesweeper of the riverine Navy was the assault support patrol boat (ASPB). These boats provided mine countermeasures for the river assault convoys during the troop transport phase of assault operations, and block and intercept water traffic in the streams near an assault operation and around the Mobile Riverine Base.

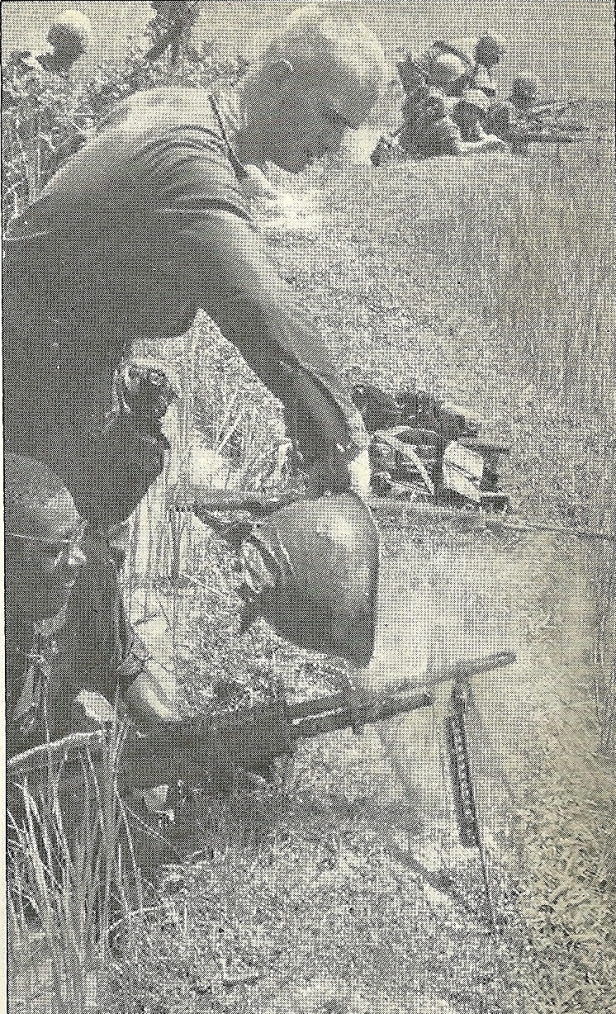

Grunts toss a grenade at a suspected enemy position as buddies cover him with fire support. Fighting in the Mekong Deltas was often fierce owing to the tenacity by which the Viet Cong sought to defend their waterway supply routes.

A forth type of craft was the command and communications boat (CCB), a floating command post for the ground force commander and boat group commander. The CCB looks much like the monitor and can be used to provide fire support.

All of the ships and boats in Task Force 117 were permanently homeported in San Diego, California, and are part of the U.S, Amphibious Force, Pacific Fleet. While operating in Vietnam, they were under the operational control of the Commander, U.S, Naval Forces, Vietnam.

Combat in a riverine environment was much the same as combat in a land environment. The same ground tactics applied. The only difference was the manner in which the troops were carried to the objective; on land the conveyance is by trucks or track-vehicles and in the Delta it was by boats.

An American GI surveys a cache of captured Viet Cong weapons taken during a pitched battle between the MRF troops, Vietnamese Marines and heavily armed VC regular forces. 266 Viet Cong were left dead on the battlefield as opposed to 52 allied losses of which 11 were Americans. This riverine battle was one of the largest fought by the MRF in western Dinh Tuong province, a key supply hub for the enemy. “Charlie” lost 226 sampans, several hundred weapons, grenades and eight command posts in this highly successful raid.

The land operation received artillery support from 105mm howitzers mounted on barges which became floating gun positions. These mobile firing bases followed the infantry along the rivers and provided fast and accurate support once they were secured snugly against the shore.

The artillery section, including battery, six firing barges, and 15 transportation boats, was commanded and furnished by the U.S, Army.

Lance Corporal Steve Kindred of clayton, Georgia, pours rice paddy water over the steaming hot barrel of the M-60 machine gun fired by Corporal Mitchell Smith of Baltimore, Maryland. This happened during a firefight against the Viet Cong in Quang Ngai Province.

Once on land, the basic tactic was to block off the enemy completely. For instance, one possible example would be to plan a movement against a known enemy position bordered on one side by a river. Infantry units would be landed to the right and left of a line of naval assault boats. The boats would form a blocking force to the south of the land objective.

Further troop concentrations could be air lifted to form a blocking force on land to the north of the objective. The infantry units that were landed to the east and west of the assault boats begin to seep north, hemming in the objective.

Air strikes and artillery fire forced the enemy from his reinforced mud bunkers.

Enemy strongholds once securely hidden in nipa palm, mangrove, and jungle thickets along the rivers were now open to attach by units of the 2nd Brigade. Night movement of the barracks ships ensured rested and fresh combat troops when they reached the operational objective.

The following videos offer actual patrol footage and additional information about the war in the Delta.

https://youtu.be/AFfb_FLP_JQ

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

I believe I may have made comments before. I was in the Air Force, assigned to the 2nd brigade, 9th Infantry and on the USS Benewah as part of the Tamale Forward Air Controller team. I kept close contact with my pilot and assisted in air strikes for the army. The Air Force was part of the MRF. Some of the hairiest times in Vietnam was part of the MRF.

LikeLike

Shows the destination of the PBR crew training that I saw at San Pablo Bay on the backside of Mare Island while I was at the shipyard in new construction for the Mariano G. Vallejo SSBN-658. They started training there in the shallow waters and marshes of the bay near the end of my time there in 1966 or 67.

Later my brother was assigned to a unit in Long Bin training Vietnamese Navy personnel on the PBR’s.

LikeLike

I was in the Air Force and was supporting the MRF by being a ROMAD on the USS Benewah, I helped coordinate air strikes for the Tamale FACS.

LikeLike

It was right on point I know I was there in 66&67 On PBRS!

LikeLike

-I was in Da Nang and Cua Viet on pusher boats and self-propelled Ammi barge We were in the background. I had my barge hit with a mine and one engine taken out by a artillery round

never see or hear anything about them

LikeLiked by 1 person

It graphically details the rigors of war and all these servicemen went through.

LikeLiked by 1 person

THIA WA A GREAT ARTICAL

LikeLiked by 1 person

I TRIED TO GET ON A RIVER PATROL BOAT BUT MY CAPTIAN WOULD NOT ALOW IT

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was on the USS MERCER in 1969. No one said anything about this Barracks ship.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great piece. I served in the BWN in 68 and 69 on the point banks (82 ft gun boat) first off an toi tied up at the apl and then cat lo base near vung tau. Travelwd many of the rivers and boarded lots of junks and sanpans.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Was on cargo ship USS MARK AKL12 on the rivers in Vietnam, same ship that was in the movie MR ROBERTS. delivering a munitions and PBR beer

LikeLiked by 1 person

I was on LST1165 Washoe Cty. We gave support to river boats on the Cau Mau peninsula, (operation Seafloat)Cau Mau/Bode rivers, 69’and 70′.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good information. I was AF forward air controller for the MRF, 67-68. That combined force did more exceptional work, in worse conditions, with less publicity, than any units I know of. Happy that Gen Westmoreland recognized them, saying “They saved the Delta” after the battles of Tet ’68

LikeLike

Yes, I was part of the Tamale FACS on the USS Benewah, radio Operator/ maintenance, helping coordinate air strikes. 1969

LikeLike

These are the guys I protected as one of the radio men on the Tamale FACS. I was one of the Air Force men helping coordinate air strikes. We were with the Army, Air Force and the Navy.. I spent time on the USS Benewah and with the army, rotating back to the AFB.

LikeLike

Great article. Brought back memories. I was in Cat Lo & Nha Be in 1968 on ARL-37. Put a bunch of boats in commission that year.

LikeLike

I was in cat lo base and on boat in 68. Was also part of MAA force there when in port. My partner was a 6ft 8on tall navy guy nicknamed willie. We ran a rat patrol jeep with m 60 mounted in backat night

LikeLiked by 1 person

iwas there with 2nd platoon 2 nd squad co c 2/60 dec 66-november 67 we trAined with the mrfa At vungtau in the rung sat tough Place to opErate and keep your weApon funCtioning mINE jammed in a fIre fighT FEB271967 SOOR ITS LATE TORED ED HINOJOSA -FC MADE SPEC 4 TEXAS ANG 76

LikeLike

I WAS PFC MADE SPEC 4 TEXAS ANG 76 WE WERE GOING TO BECOME pART OF THE REGULaR MILITARY AND TRAINED AND RUN ,I COULDNT HANDLE PT ANY MORE I Got OUT tomuch gung ho bs

LikeLike

Good article, how about honorable mention for the LSMR’s?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Skip, I am unfamiliar with that term.

LikeLike

Landing Ship Medium Rocket. There were four that were part of the Mobile Riverine Force. USS Clarion River, USS White River, USS St. Francis River, and the USS Cannonade. They all tied up at the pier with the PBRs in Cam Rahn Bay. Google any of the names and you will learn something..

Kind regards,

Skip

LikeLike

what about the “4.2” mortor firing barges?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Any photos? Care to write something about them and I’ll include into the article.

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this article. Thanks

From: Cherries – A Vietnam War Novel To: lfresquez2000@yahoo.com Sent: Tuesday, March 28, 2017 2:47 PM Subject: [New post] The Delta River War – Brown Water Navy #yiv9641652856 a:hover {color:red;}#yiv9641652856 a {text-decoration:none;color:#0088cc;}#yiv9641652856 a.yiv9641652856primaryactionlink:link, #yiv9641652856 a.yiv9641652856primaryactionlink:visited {background-color:#2585B2;color:#fff;}#yiv9641652856 a.yiv9641652856primaryactionlink:hover, #yiv9641652856 a.yiv9641652856primaryactionlink:active {background-color:#11729E;color:#fff;}#yiv9641652856 WordPress.com | pdoggbiker posted: “A unique force of riverine vessels sought and successfully plugged the Viet Cong’s river supply routes by applying amphibious search and destroy tactics that hadn’t been used by the American military since the Civil War, a hundred years earlier.The Mo” | |

LikeLiked by 1 person

Good article, pdogg. I know several other people who will enjoy a trip to their past.

LikeLiked by 1 person