By Terry Leonard, Stars and Stripes

As fellow troopers aid wounded comrades, the first sergeant of A Company, 101st Airborne Division, guides a medevac helicopter through the jungle foliage to pick up casualties suffered during a five-day patrol near Hue, April 1968. /ART GREENSPON/AP

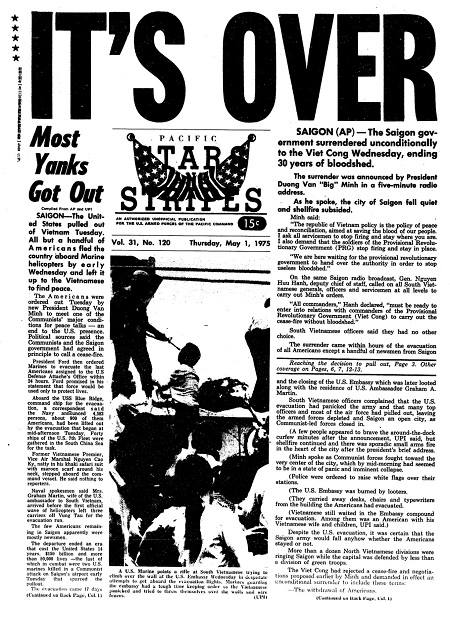

South Vietnam, May 20, 1965: U.S. helicopters rake the perimeter of a landing zone with rockets and machine-gun fire before dropping off troops brought in from Binh Hoa. Mike Mealey/Stars and Stripes

South Vietnam, May 20, 1965: U.S. helicopters rake the perimeter of a landing zone with rockets and machine-gun fire before dropping off troops brought in from Binh Hoa. Mike Mealey/Stars and Stripes

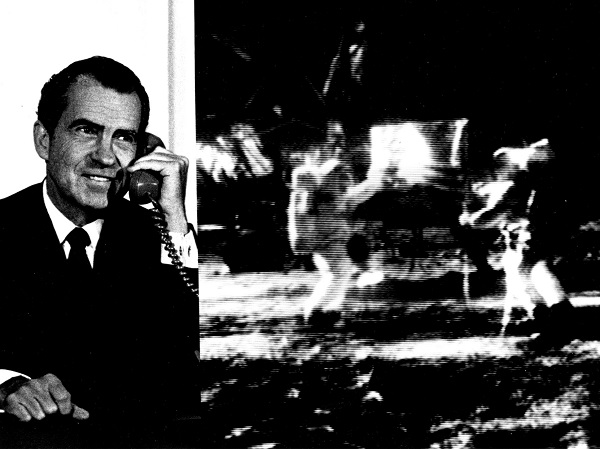

When Neil Armstrong took his small step for man in the lunar dust in July 1969, Americans saw it as proof there were no Earthly limits. Nothing then seemed beyond the reach of American power, prestige and know-how. It took Vietnam to expose the hubris in that sentiment.

When Neil Armstrong took his small step for man in the lunar dust in July 1969, Americans saw it as proof there were no Earthly limits. Nothing then seemed beyond the reach of American power, prestige and know-how. It took Vietnam to expose the hubris in that sentiment.

The American Century was at its zenith. Unrivaled U.S. wealth and prosperity, predictable fruits of the postwar Pax Americana, lifted national influence to new heights globally. Hollywood, rock music, blue jeans and hamburgers carried American culture, taste and values to the far corners of the world.

Yet with images of Apollo 11 fresh on the mind, Vietnam forced Americans to accept limits to U.S. power and to acknowledge their reach had exceeded their grasp. With apologies to Robert Browning, that troublesome realization was not what they believed a heaven was for.

Fifty years later, the Vietnam War remains an enigma. Its legacy distorted by folklore, myth, political spin, cloudy memories and the perverted history of feature films and popular fiction. Yet it remains clear the war changed America in profound ways still not understood.

It changed who we are and how we see ourselves. It fundamentally revised our view of the world and the world’s view of us. It reshaped our institutions, particularly the military. It altered not only how we fight wars, but when and why we choose to fight.

Stars and Stripes is commemorating the Vietnam War at 50 annually with a series of stories and special projects intended to add context and understanding to the history of that war and to the changes it wrought. The project examines the fighting abroad and the protests, politics and turmoil at home. It includes the voices of veterans who fought and those of others who marched at home for peace.

More than 58,000 Americans and at least 1.5 million Vietnamese died in the war that divided the country as nothing else had done since the Civil War.

“No event in American history is more misunderstood than Vietnam. It was misreported then, and it is misremembered now,” former President Richard Nixon wrote in his 1985 book “No More Vietnams,” a selective history and apologia for his role in the tragic war.

Americans fought fiercely and gallantly in Vietnam. The Medal of Honor was awarded to more than 250 individuals. U.S. troops won nearly every significant battle. Yet it was all in vain. Many fighting men would feel betrayed by political leaders and people at home who turned against the war.

At home, the war taught a generation of young people not to trust their government. In an astonishingly short period of time they taught their parents and even some political leaders.

“The biggest lesson I learned from Vietnam is not to trust our own government statements. I had no idea until then that you could not rely on them,” former Sen. J. William Fulbright told the New York Times in 1985, a decade after the war ended.

The government also didn’t trust its people. Security agencies spying on civil rights leaders and political dissidents added people who spoke out against the war to their surveillance lists. Later Senate investigations detailed widespread illegal intelligence gathering on U.S. citizens.

The government also didn’t trust its people. Security agencies spying on civil rights leaders and political dissidents added people who spoke out against the war to their surveillance lists. Later Senate investigations detailed widespread illegal intelligence gathering on U.S. citizens.

Anti-war and civil rights protesters were also portrayed in government-run campaigns of character assassination as anti-American or communist sympathizers, sometimes with violent consequences. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Chicago police savagely attacked and beat anti-war protesters. A federal investigation later would term it a police riot.

Anti-war and civil rights protesters were also portrayed in government-run campaigns of character assassination as anti-American or communist sympathizers, sometimes with violent consequences. At the 1968 Democratic National Convention, Chicago police savagely attacked and beat anti-war protesters. A federal investigation later would term it a police riot.

In May of 1970, National Guardsmen opened fire on anti-war protesters at Kent State University in Ohio, killing four and wounding nine. Just 10 days later, police killed two and wounded 12 when they fired on African-American students protesting the war at Jackson State College in Mississippi.

Kent State triggered a nationwide student strike that closed hundreds of colleges and universities and became a symbol of how the war divided the country. In a Newsweek poll three weeks after the shootings, 11 percent of the respondents blamed the National Guard and 58 percent the students. The shootings at predominately African-American Jackson state were largely ignored.

When the war began in the Sixties many had already begun to question a U.S. international policy shaped by the cold war narrative of the Red Menace and the Domino Theory. Domestically, American society was under pressure from many sides to become more inclusive and fair.

The civil rights movement forced a reluctant country to confront its values and its shameful past. The sexual revolution and the women’s rights movement sought to fundamentally change how Americans lived, loved and worked. It reshaped gender roles and widened a growing gap between the younger and older generations.

The civil rights movement forced a reluctant country to confront its values and its shameful past. The sexual revolution and the women’s rights movement sought to fundamentally change how Americans lived, loved and worked. It reshaped gender roles and widened a growing gap between the younger and older generations.

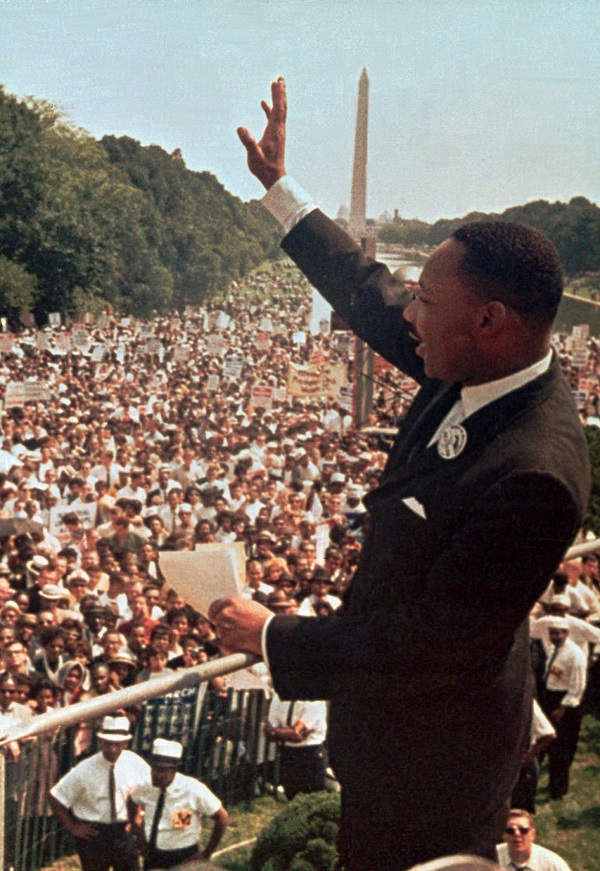

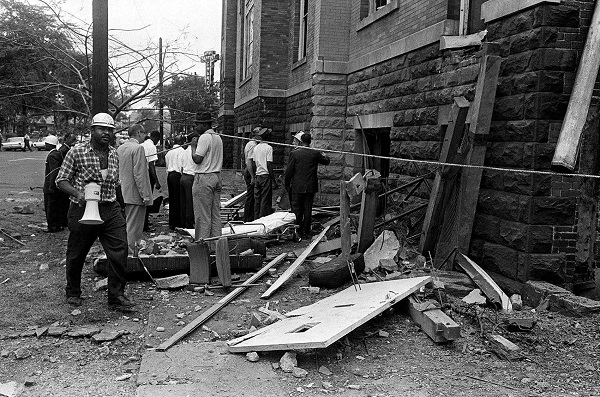

The assassination of President John F. Kennedy stunned the country and exposed deep and dark divisions. The subsequent murders in 1968 of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy destroyed lingering illusions about an idyllic America and raised troubling questions about our violent national character.

The mostly peaceful civil rights movement was fiercely and violently resisted. Police brutally suppressed peaceful demonstrations, and not just in the south. Civil rights workers were murdered or beaten, black churches were bombed, black men lynched. Race riots in the ‘60s rocked New York, Newark, Philadelphia, Detroit, Chicago and Los Angeles. Americans were shocked by television images of National Guardsmen and U.S. paratroopers, locked and loaded, patrolling the streets of burning American cities.

America’s disaffected youth recoiled from society and their discontent gave rise to an anti-authoritarian counterculture that sought to reinterpret the American dream. Peace and love replaced duty and honor. The popular refrain “Don’t trust anyone over 30,” defined the boundaries of the generation gap.

Entertainers such as Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez and others made rebellion part of popular culture. Dylan caught the emerging tenor in his 1964 song “The Times They Are A-Changin’”:

Come mothers and fathers

Throughout the land

And don’t criticize

What you can’t understand

Your sons and your daughters

Are beyond your command

Your old road is

Rapidly agin’

Please get out of the new one

If you can’t lend your hand

For the times they are a-changin’

The Harvard psychologist Timothy Leary became a counterculture guru by advocating mind-altering drugs such as LSD. He popularized the phrase “Turn on, Tune in, Drop out.” He was fired by Harvard, but he was seen as something of a philosopher by the “sex, drugs and rock and roll” culture of the ‘60s. So much so that even today a common joke is: “If you can remember the ‘60s, you weren’t really there.”

Despite the obvious excesses, mainstream society began to embrace causes of the youth movement, particularly its anti-war sentiment. Peace marches that began with a few thousand students grew into marches by tens of thousands from all walks of life.

Nixon sought to deflect criticism of the war and growing distrust in government. He spoke in1969 of the “silent majority” of Americans whose views supported him and the war but whose voices were being drowned out by a more vocal minority.

That was the summer Apollo 11 landed on the moon and confirmed our belief in American exceptionalism. Americans constantly boasted that if we could go to the moon, we could do anything.

Many historians argue that a series of U.S. presidents and their military and political aides believed it too and erroneously assumed military might would win in Vietnam.

“Tell the Vietnamese they’ve got to draw in their horns or we’re going to bomb them into the Stone Age,” warned Gen. Curtis LeMay, the Air Force chief of staff, in May 1964. U.S. warplanes dropped more tons of explosive on Vietnam than fell on Germany, Japan and Italy in World War II, but his hollow threat would later be lampooned by critics of the war.

In just three years, that overconfidence retreated to a position of curious optimism. Walt Rostow, President Johnson’s national security adviser, tried to deflect bad news about the war in 1967 by saying: “I see light at the end of the tunnel.” That light, his critics joked, was an oncoming train.

Even the curious optimism faded.

Two years later, Nixon, under pressure to end the war vowed: “I’m not going to be the first American president to lose a war.”

Nixon later claimed victory in Vietnam but blamed a hostile press and an irresponsible Congress for “losing the peace.” In the book “Chasing Shadows: The Nixon Tapes, the Chennault Affair and the Origins of Watergate,” journalist Ken Hughes said this year that newly released transcripts of FBI wiretaps indicated then presidential candidate Nixon ordered the sabotage of the Paris peace talks in October of 1968, apparently to bolster his election chances that November.

Over the years, news coverage of the war shifted from supportive to an increasingly grim portrayal of the fighting. As the reporting became increasingly negative, as casualties continued to mount, public doubts grew dramatically.

One of the most enduring legacies of Vietnam and its negative impact on public opinion and policy is the Vietnam Syndrome, the name to the paralyzing effect on U.S. foreign policy brought on by the fear of becoming mired in another quagmire, a questionable war with no clear objectives and a defined end game. Every president since the war ended has had to deal with the syndrome.

The Vietnam War was perhaps the most publicized war in American history and certainly the first televised war with ghastly images nightly on the evening news.

“Television brought the brutality of war into the comfort of the living room. Vietnam was lost in the living rooms of America – not on the battlefields of Vietnam,” Marshall McLuhan, the highly regarded Canadian philosopher of communication theory told the Montreal Gazette in 1975.

That coverage of the Vietnam War and its impact on the public became a serious concern. Early in 1968 polls showed 61 percent of Americans supported the war. By years end, 53 percent opposed it. By the time Armstrong landed on the moon, 58 percent opposed it and s upport for the war would continue to fall.

“Vietnam was the first war ever fought without censorship. Without censorship, things can get terribly confused in the public mind,” retired Gen. William Westmoreland, the commander in Vietnam from 1964 to 1968, would tell Time magazine in 1982.

For some, the key lesson learned was that it was the coverage of failed policies, and not the policy failures themselves, that caused Americans to lose faith and confidence in government.

The military now tightly controls access to a battlefield. With the policy it can and at times has limited what could be seen and by extension, what could be reported. Critics argue the policy supports the old adage: “Truth is the first casualty of war.”

Although support for the war dwindled, until Saigon finally fell April 29, 1975, many still refused to believe we could lose. Today, many scholars contend the war marked the loss of American innocence. It deeply divided a nation unified by World War II and the division and distrust of government continues to grow.

leonard.terry@stripes.com

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

My brother served in Veitnam. He was not the same when he came back home.very sad!

Your artical really helped me understand a lot. Thanks

LikeLike

MILITARY LIVES MATTER. PERIOD…..END OF DISCUSSION !!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

After the debacle in Southeast Asia, we said never again. What a joke-! Our corrupt gov’t goes right on lying to the people, starting wars of choice for the oil barons and young men continue to die in questionable conflicts enter into without a congressional declaration of war. A pox on every self-serving political piece of amphibian dung in the Washington DC Beltway-!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I enjoyed the article very much, I served two tours in Vietnam, we won the battles but lost the war because of political involvement, we were fighting with our hands tied because of Rules of engagement.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great

LikeLiked by 1 person